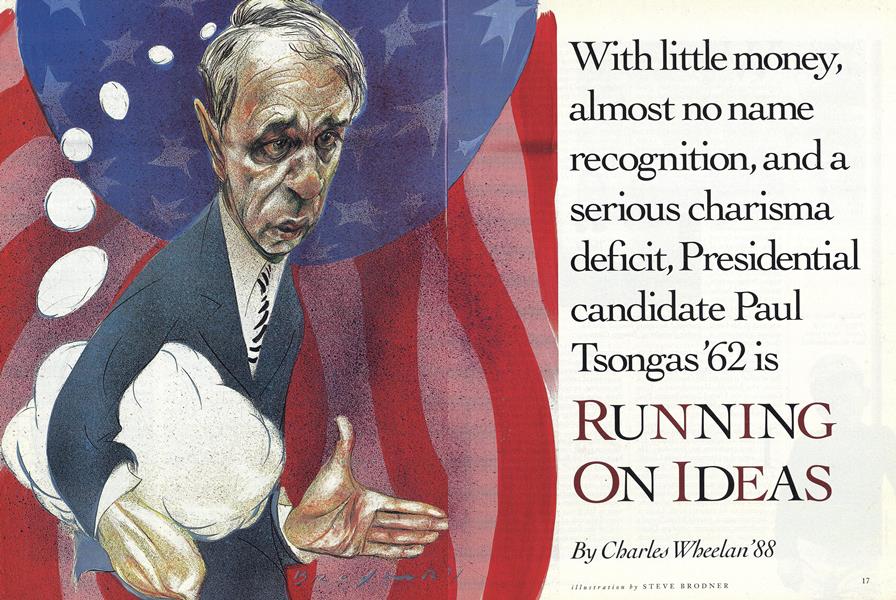

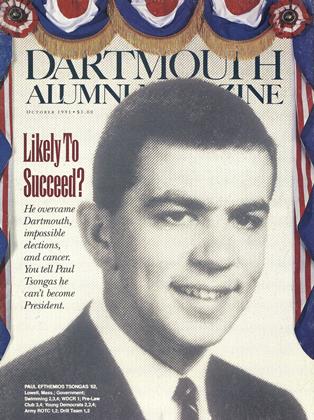

With little money, almost no name recognition, and a serious charisma deficit, Presidential candidate Paul Tsongas '62 is

When THE TSONGAS entourage gets out of a limousine, it is hard to tell which one is the candidate. Not tall, not handsome, not particularly eager to shake hands, Paul Tsongas has built a successful political career out of seeming ill-suited for politics. The New York Times deemed him "terminably earnest"; and when he ran for the Senate in 1978, the Boston Globe described him as "an obscure first-term Congressman." Given that he was in his second term, the report in his home state's paper confirmed that he was indeed obscure.

In the nine years he served in Washington, Tsongas established a reputation as a bright, hardworking, and well-respected lawmaker and never once hosted a Washington dinner party. In the age of the soundbite, the Tsongas campaign position paper is 85 pages long, single spaced and he has never lost an election. This time the odds are long, but the same was true in his battle against lymphoma, a then-incurable form of cancer that he has since beaten. Analysts insist that the country is not ready for another liberal Greek Democrat from Massachusetts. But whether it was for the Dartmouth swim team, the Lowell, Massachusetts, City Council, or the United States Senate, Paul Tsongas has always been the unknown candidate who ends up making it.

IN THE FALL OF 1958, PAUL EFTHEMIOS Tsongas was an unlikely future candidate for President. He arrived at Dartmouth from Lowell, where his father owned Tsongas Cleaners. His roommates remember Paul as a young man struggling to find a niche. "He just seemed in a strange, alone place. Of the three of us, he seemed to be the one most adrift, a kind of morose, moody fellow," recalls freshman roommate Stephen Quay. Tsongas worked in the Dartmouth dining hall, was a regular at Dartmouth sporting events, and joined the Dartmouth Players, according to his roommates. He made a false start in chemistry and later majored in government.

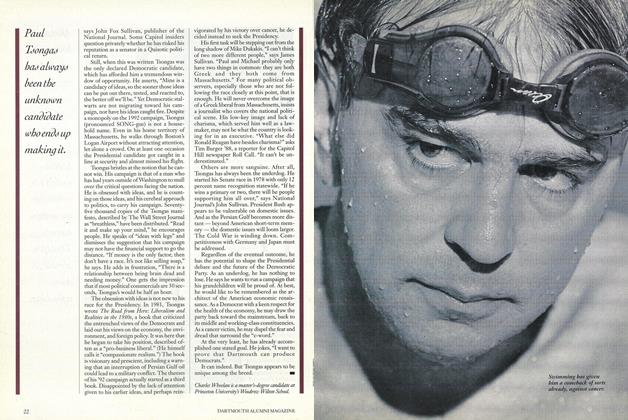

The experience was not entirely a happy one. Tsongas points out that he was a student in the "Animal House" era, a scene in which he did not fit or have any particular interest. "I think the introduction of women and the increased respect for intellect has been very positive," he now says. Roommates recall a somewhat introverted student who liked to discuss intellectual subjects. "A lot of guys just wanted to get plowed on a Saturday night. That was not Paul," recalls Don Ulrich '62, Tsongas's roommate sophomore and junior years. "He was an unhappy fellow when I knew him," Ulrich says. A notable exception was swimming. Tsongas joined the team as a mediocre swimmer and eventually earned his varsity letter. (He was to return to the sport 28 years later to repair lung damage caused by his cancer treatment and to prove his health and fitness to the nation.) He still speaks fondly of the swim team and of Coach Karl Michaels. The swimming experience struggling freshman to varsity letterman is a transition that would characterize him, especially in his political endeavors, for years to come. Swimming, according to both Tsongas and those who knew him at Dartmouth, provided the self-esteem he had been lacking. "By the time he graduated, it was clear that he had a lot of determination and ability," says Quay.

Dartmouth is not an experience to which Tsongas refers often, or one that seems to have shaped his decision to enter politics. He is almost "cynical" about his Dartmouth experience; he considers the place anti-intellectual, says a journalist who still covers Tsongas and asked not to be named. Tsongas speaks more often of his two years as a pioneer in the Peace Corps. In 1962, he answered the call of John F. Kennedy to be part of the first group of volunteers sent abroad. The destination was Ethiopia, where he taught in a rural school and worked with villagers to build a dormitory. He describes the experience as "the best two years of my life" apart from family, and it was there that his political career was hatched. "Politics is trying to feel about yourself as I felt about myself over there a sense of worth," he says.

Yale Law School lay between him and a career in public office. He found law school unrewarding and has never had a passion for the profession. He worked during the summers as an in-tern for Congressman F. Bradford Morse, a liberal Republican from the Massachusetts district Tsongas would later represent. By then, 1968, Vietnam

was raging: Tsongas considered volunteering as a medic for the Green Berets in Vietnam but was dissuaded by friends. He applied to the Agency for International Development to work in Vietnam but was turned down. He finally opted for a second tour in the Peace Corps as an administrator in the West Indies.

TSONGAS'S VISIONS OF THE economy were not shaped at Dartmouth, or even in Washington. They originate from Tsongas Cleaners in Lowell, Massachusetts. It was here that he learned firsthand about the meaning of economic decline. (Paul's father emigrated from Greece at age four and later attended Harvard. His mother, born in the United States, was institutionalized with tuberculosis when Paul was 18 months old and died when he was seven.) Located at the confluence of the Merrimack and Concord Rivers, Lowell was at one time the preeminent planned industrial city in the United States. Here the textile mills of Great Britain had been recreated to tap Yankee labor. Visitors, including President William Howard Taft, Mark Twain, and the Prince of Wales, flocked to see the industrial wonder.

But it was a city better suited for the nineteenth century than the twentieth. The textile industry began to move south. Labor was cheaper, and the southern mills were closer to the source of raw materials. A once vital city became outdated and depressed. "Lowell became a city where there was no future," recalls James Sullivan, former city manager of Lowell and current president of the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce. It was in this environment that Paul grew up working at Tsongas Cleaners. "We worked, and we worked, and we worked . . ." he recalls, his voice trailing off. When Tsongas talks about the importance of competing with Japan and Germany, he is thinking about Lowell, Massachusetts.

Competing internationally is a theme to which he returns repeatedly. "[Reagan-Bush] have taken the economic legacy of our ancestors and squandered it. They have taken the economic promise of our children and destroyed it," he tells a Westchester, New York, audience emphatically. "We will be the first generation because of Reagan-Bush to give our children less. That is generationally immoral."

Tsongas's urgent message is a radical departure from the feel-good politics of Ronald Reagan or the Gulf-victory euphoria of George Bush. Tsongas is banking that the country is ready, or will soon be ready, to accept his somber message. "George Bush is not unbeatable," he insists. "Find people who will tell you that George Bush has taken this country on the right path. There is not one. Are you happy with the condition of the economy, the cities, the environment?" he challenges.

Tsongas, who likes to portray himself as an economic Paul Revere, paints a single scenario in which he will be elected President. "Two things must happen," he says. "First, the country recognizes its economic peril; and second, people recognize that I know how to meet that peril. Bush can't do it because he can't admit [that there is a problem]. The Democrats have no economic policy." Tsongas is convinced that the U.S. economy is in a downward slide that will drag our standard of living with it. He sketches a diagram that shows a series of business cycles that slope steadily downward. "I grew up in Lowell during the decline," he says. "I know what this feels like."

His sensitivity to decline does not make him a man of the people. His speaking style, says Ellen Goodman, Globe columnist, "makes Mike Dukakis look charismatic." Small talk does not come easily, if at all. After an hour and a half of travel and interviews with a writer from Dartmouth, he still couldn't remember the writer's name. The lapse almost seems refreshing in a world of glib politicians. Tsongas has more important things on his mind. "When people meet Paul Tsongas, they like him. His honesty and candor come through," says James Sullivan.

When Paul Tsongas speaks, it's not just the Republicans who catch hell. An important part of his message is a plea to the Democratic Party to "keep its heart and soul and get a brain," says his press secretary, Peggy Connolly. For Tsongas, that means preserving the party's strong record on social issues ("the family jewels," he calls it) while convincing the voting public that the Democrats are capable of looking after the economy, something traditionally considered Republican domain. Tsongas tells a story about a vote early in his career in the House of Representatives for an investment tax credit bill. "That's a business bill," he was told. "You're a Democrat. You've got to vote against it." "The fact is, that bill did more for my district than I did," Tsongas points out years later.

"You can't redistribute wealth that doesn't exist," he tells group after group. If there is a central theme to his campaign, that is it. Democrats are consumed by redistributing a pie that, because of competition with Japan and Germany, is shrinking. "You cannot be pro-jobs and antibusiness," he insists. Tsongas, according to the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, had the most liberal voting record in the U.S. Senate his first year more liberal even than his Massachusetts colleague, Senator Edward Kennedy. But Tsongas has since spent seven years in the private sector, serving on the corporate boards of Boston Edison, Shawmut Bank, Wang Laboratories, and 11 other profit and non-profit organizations. He now supports selective tax cuts on capital gains, efforts to boost the savings rate, and a relaxation of anti-trust laws. He supports nuclear power as a way of reducing the nation's dependence on fossil fuels. And he favors abolishing quarterly reports in order to foster more long-term thinking in corporate America.

Despite his "pro-business" label, Tsongas has not inspired the business community. "I have not seen any indication that they support Tsongas or that they care much about him at all," says the National Journal's John Fox Sullivan. Tsongas does not accept that, and the evidence is, once again, Lowell. The revitalization of his hometown was one of Paul Tsongas's most significant achievements as a legislator. In many ways, it molded his later beliefs about the power of the private sector. In the mid-19705, the city-was a shell. As the final salt in the wound of its decline, the abandoned textile mills proved too expensive even to remove. They remained as a reminder of the shifting winds of capitalism. "There wasn't anybody under 40 in the city of Lowell," recalls Dick Giesser, Dartmouth '53 and a longtime player in Massachusetts politics.

The traditional federal remedies had failed to stem the decline. Paul Tsongas became the point man for a revitalization in which the private sector was a full partner. Giesser describes Tsongas as "very persistent, very bright, very persuasive." He shepherded legislation through Congress making Lowell a National Historic Park. Working with other political leaders, he put together a financial package to encourage and assist Lowell's businesses, notably the computer company Wang Laboratories and its suppliers. This private investment was the key to Lowell's stunning reversal.

Tsongas is fond of saying that only Nixon, a diehard anti-communist, could have initiated relations with Red China. His corollary is that it will require a liberal Democrat to create a government policy favorable to the American business community without being accused of being in the pocket of big business. Enter Tsongas. "I've never met a businessman who said we cannot compete. What I get is anger because we're not trying," he says.

DESPITE AN APPEARANCE AND demeanor to the contrary, Paul Tsongas is an ambitious politician with a career path that took him from the Lowell City Council to the U.S. Senate with intermediate stops as Middlesex County Commissioner and U.S. Congressman in less than ten years. As a senator, he had a reputation for being serious-minded, well-prepared, shrewd, and even likeable. The Dartmouth student who liked to talk about his government classes was at the pinnacle of political success when he received an honorary degree from his alma mater in 1983.

His return to Hanover two years later as a Montgomery Fellow was dramatically different. By then he had been diagnosed with lymphoma, a form of cancer considered incurable at the time. Tsongas announced he would not seek re-election to the Senate in 1984. Spending time with his family, he said, was more important than his political career. (He subsequently wrote a book entitled Heading Home that detailed his discovery and early treatment of the disease.)

By 1986, his condition had worsened and doctors prescribed radical but still experimental treatment (a procedure he now compares with what must be done to the U.S. economy). He underwent a bone marrow transplant and six weeks of recovery in an isolated, sterile room. He says of the experience, "You think differendy; you have a different set of values. You begin to think genera tionally. I never did that before. Hopefully it gives me a broader perspective; you don't go through that and come out the same person." Five years later, there has been no recurrence of the disease. Tsongas's oncologist, Tak Takvorian, has pronounced the chances of a recurrence "so remote as to be negligible."

During the illness, and in all other facets of his life, Tsongas leaned heavily on his family. He met his wife, Niki, while he was a Congressional intern in Washington and they were engaged only a few months later. (She jokes that the party at which they met was one of the few Paul ever attended in Washington.) They have three children, Ashley 17, Katina 13, and Molly 9. According to Tsongas, the family operates like the U.N. Security Council; each family member has a veto; the decision to run for President was unanimous.

DOES PAUL TSONGAS, DARTmouth's first major-party Presidential candidate since Nelson Rockefeller '30, have a chance to win the White House, or even the nomination? Tsongas himself says half-seriously, "If you asked the people in my Dartmouth class who was most likely to run, they would get to me on about the fourth day of guessing." It is typical of his self-deprecating sense of humor, a tool he uses often on the campaign trail. The most serious problem for Tsongas, however, is that many political analysts also might take days to come up with his name. Most were shocked by his decision to seek the Presidency and now give him little or no chance of even capturing the nomination. "People had sort of forgotten about him," says John Fox Sullivan, publisher of the National Journal. Some Capitol insiders question privately whether he has risked his reputation as a senator in a Quixotic political return.

Still, when this was written Tsongas was the only declared Democratic candidate, which has afforded him a tremendous window of opportunity. He asserts, "Mine is a candidacy of ideas, so the sooner those ideas can be put out there, tested, and reacted to, the better off we'll be." Yet Democratic stalwarts are not migrating toward his campaign, nor have his ideas caught fire. Despite a monopoly on the 1992 campaign, Tsongas (pronounced SONG-gus) is not a household name. Even in his home territory of Massachusetts, he walks through Boston's Logan Airport without attracting attention, let alone a crowd. On at least one occasion the Presidential candidate got caught in a line at security and almost missed his flight.

Tsongas bristles at the notion that he cannot win. His campaign is that of a man who has had years outside of Washington to mull over the critical questions facing the nation. He is obsessed with ideas, and he is counting on those ideas, and his cerebral approach to politics, to carry his campaign. Seventyfive thousand copies of the Tsongas manifesto, described by The Wall Street Journal as "breathless," have been distributed. "Read it and make up your mind," he encourages people. He speaks of "ideas with legs" and dismisses the suggestion that his campaign may not have the financial support to go the distance. "If money is the only factor, then don't have a race. It's not like selling soap," he says. He adds in frustration, "There is a relationship between being brain dead and needing money." One gets the impression that if most political commercials are 30 seconds, Tsongas's would be half an hour.

The obsession with ideas is not new to his race for the Presidency. In 1981, Tsongas wrote The Road from Here: Liberalism andRealities in the 1980s, a book that criticized the entrenched views of the Democrats and laid out his views on the economy, the environment, and foreign policy. It was here that he began to take his position, described often as a "pro-business liberal." (He himself calls it "compassionate realism.") The book is visionary and prescient, including a warning that an interruption of Persian Gulf oil could lead to a military conflict. The themes of his '92 campaign actually started as a third book. Disappointed by the lack of attention given to his earlier ideas, and perhaps reinvigorated by his victory over cancer, he decided instead to seek the Presidency.

His first task will be stepping out from the long shadow of Mike Dukakis. "I can't think of two more different people," says James Sullivan. "Paul and Michael probably only have two things in common: they are both Greek and they both come from Massachusetts." For many political observers, especially those who are not following the race closely at this point, that is enough. He will never overcome the image of a Greek liberal from Massachusetts, insists a journalist who covers the national political scene. His low-key image and lack of charisma, which served him well as a lawmaker, may not be what the country is looking for in an executive. "What else did Ronald Reagan have besides charisma?" asks Tim Burger 'BB, a reporter for the Capitol Hill newspaper Roll Call. "It can't be underestimated."

Others are more sanguine. After all, Tsongas has always been the underdog. He started his Senate race in 1978 with only 12 percent name recognition statewide. "If he wins a primary or two, there will be people supporting him all over," says National Journal's John Sullivan. President Bush appears to be vulnerable on domestic issues. And as the Persian Gulf becomes more distant beyond American short-term memory the domestic issues will loom larger. The Coid War is winding down. Competitiveness with Germany and Japan must be addressed.

Regardless of the eventual outcome, he has the potential to shape the Presidential debate and the future of the Democratic Party. As an underdog, he has nothing to lose. He says he wants to run a campaign that his grandchildren will be proud of. At best, he would like to be remembered as the architect of the American economic renaissance. As a Democrat with a keen respect for the health of the economy, he may draw the party back toward the mainstream, back to its middle and working-class constituencies. As a cancer victim, he may dispel the fear and dread that surround the "c-word."

At the very least, he has already accomplished one stated goal. He jokes, "I want to prove that Dartmouth can produce Democrats."

It can indeed. But Tsongas appears to be unique among the breed.

Paul was born in thestruggling city ofLowell. Seven yearslater his mother died.

"We worked, and we worked, and weworked," he says of himself and hisfather, founder of Tsongas Cleaners.

Things got better atDartmouth when heworked, his way up tovarsity swimming.

Dartmouth gave him an honorarydegree in 1983. His return two yearslater was to be dramatically different.

As wife Niki looked on in 1984, Tsongas, suffering from cancer,announced that he would not run for reelection to the Senate.

Tsongas's visions ofthe economywere notshaped atDartmouth,or even inWashington.

"He was anunhappyfellow whenI knew him"days DonUlrich '62

Tsongas'surgentmessage isa radicaldeparturefrom thefeel-goodpolitics ofRonaldReagan orthe Gulfvictoryeuphoriaof GeorgeBush.

After anhour anda half oftravel andinterviewwith awriter fromDartmouth,he stillcouldn'trememberthe writer'sname.The lapsealmostseemsrefreshing.

PaulTsongashas alwaysbeen theunknowncandidatewho ends upmaking it.

Charles Wheelan is a masters-degree candidate atPrinceton University's Woodrow Wilson School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

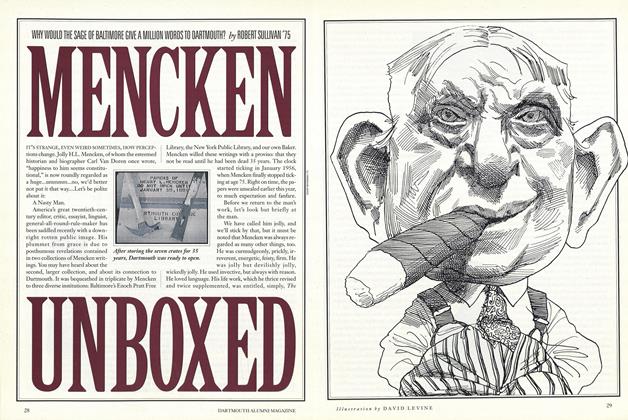

FeatureMENCKEN UNBOXED

October 1991 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

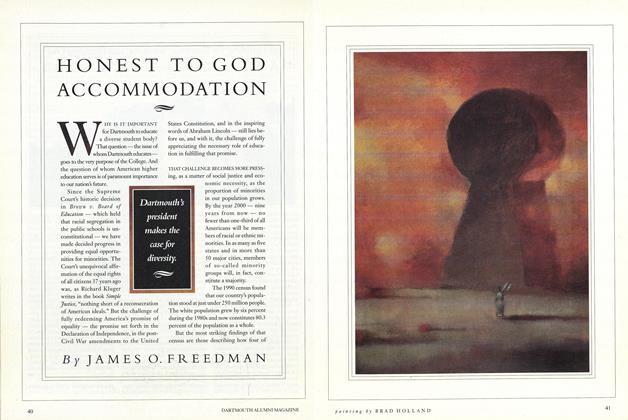

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

October 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

FeatureThe Masked Stork

October 1991 By William DeJong '73 -

Feature

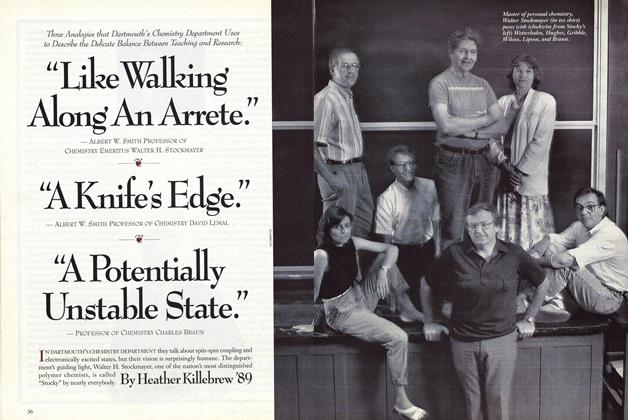

Feature"Like Walking Along an Arrete."

October 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1991 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1988

October 1991 By Chuck Young

Features

-

Feature

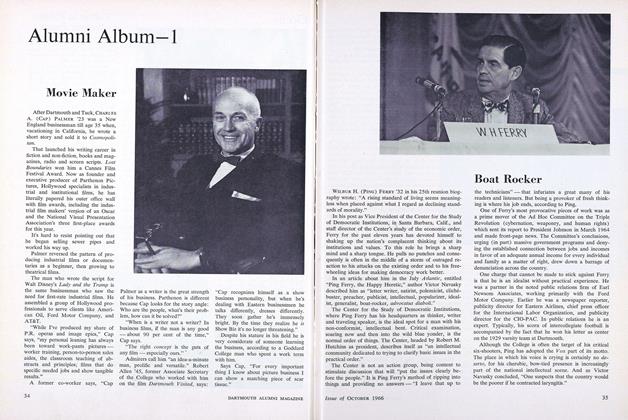

FeatureBoat Rocker

OCTOBER 1966 -

Feature

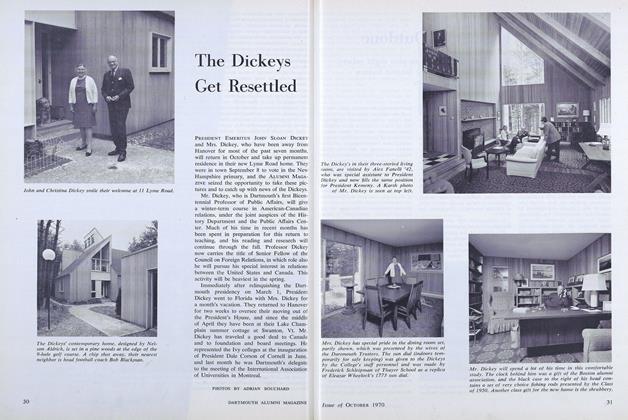

FeatureThe Dickeys Get Resettled

OCTOBER 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe American Dream

JANUARY 1972 By A.T.G. -

Feature

FeatureAs the Century Turned

JUNE 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureBaker Holds the Key

DECEMBER 1965 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

FEATURE

FEATURESix Great Food Finds

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By JANE STERN