CURIOUS activities take place on prominent campuses, in large cities, and around areas of strategic military significance. Out on the Pacific Ocean, a few men in a yacht attempt to sail into a nuclear weaponstesting zone as zero hour approaches. Civil Defense drills are picketed in New York City. A clamor erupts after a motion picture portrays the slow, agonizing death of the isolated, last-surviving remnant of mankind in the mid-1960s. Mass marches involving many thousands of people shake England while pressure politics pushes for unilateral disarmament. Unwelcome visitors suddenly appear around submarine ports. And a 6,500-mile hike from San Francisco to Moscow gets underway.

These events show what an interesting phenomenon pacifism is, how militant it sometimes becomes, and that it is on the rise again, perhaps to exceed the peaks it reached in the turbulent 1930s. Naturally, pacifism and military preparations have taken on new meaning, because both the survival and the humanity of man are threatened as never before. My concern about pacifism is based particularly on the belief that it should be better understood rather than praised, condemned, or ignored outright, and that its growth - especially in its possible appeal for many young, impressionable people - suggeststhat it is not negligible. Also, we must combat apathy and complacency, and stop taking things for granted; we need to face the problems of war and peace, and other issues, more actively, openly, and objectively.

It is well to know how some of today's trends and issues are regarded by students, and our particular concern here is the Dartmouth campus. My study on this matter - admittedly quite incomplete - began with my observation of student pacifism, which marked a strong return to issues carrying directly beyond the campus. The highlights of all this came in the spring of my junior year, when several lively letters hit the college newspaper, following a feature article on military opportunities and obligations, and how to avoid being drafted; and when America's leading pacifist, the Rev. A. J. Muste, visited Dartmouth to discuss "pacifism of a fairly radical type.''

Perhaps the most striking event, however, was the demonstration staged by a handful of outspokenly pacifist students (members of the ultra-liberal Dartmouth Human Rights Society) against the Armed Forces Day ceremonies conducted by the College's ROTC units. This affair, which failed to exhibit any virtues of pacifism, and the unfortunate objections against Dr. Muste's thought-provoking lecture before it was given two days later, were happily followed by more constructive activities: public discussions on pacifism, ROTC, religion and war, ways to peace, and so forth.

A year later, in an effort to learn more about pacifism and related issues, I approached my classmates as an unidentified investigator with a seven-page general survey questionnaire covering a wide range of topics. This was distributed and later collected through the facilities of the Great Issues Course. The completion of the rather lengthy forms was optional, and in order to encourage frank replies, the purpose of studying pacifism was deliberately hidden among numerous other subjects, and the students were asked not to sign their names. The Senior Class was chosen because of its greater exposure to the issues through G. I. and more experience in higher education and campus life.

My main objective was that of a psychology research project: to compare pacifists with non-pacifists in terms of overall demand for change (in conditions other than those of military life), intellectualism and individualism, reaction against authority in general, and aggression in verbal and unorthodox manners (in agitation, debates, crusades, etc.); the pacifists were expected to appear more radical or unusual in all four areas. Although my hypotheses were in no way disproved, certain difficulties proved that the pacifists would show important contrasts only with exact opposites, the "antipacifists" or "reactionaries."

Since these two groups were so small, even when taken together, their differences are of little concern to an alumni magazine, which is no psychology journal. Out of 183 returns (about 28% of a possible 650 or so), only 11 men or 6% were pacifist and only 13 or 7% were anti-pacifist. What should concern us here is that neither pacifism nor undue intolerance toward it seems to be prevalent on campus; this undermines any charges that warmongering and McCarthyism thrive at the College, as well as some claims by notoriously reactionary characters that pacifism is popular, everywhere, and deeply ingrained (even in apathetic individuals) at schools like Dartmouth, that most students at such schools confuse pacifism with peace, and that they are thus rendered helpless and disloyal by liberal education "in the name of academic freedom."

However, apathy and some more definite and interesting general trends were brought to the fore by the students' answers. It is these things, touched upon by the whole group, that I want to discuss, rather than what pacifists and nonpacifists have and do not have in common, and what the major arguments used both for and against pacifism are. Let me simply say here that I for one recognize a distinction between peaceful coexistence with people of all nationalities and "peaceful coexistence" with communism; and I feel that pacifism - if it goes beyond individual conscientious objection and minority movements, and involves unilateral disarmament or disarmament with only limited controls - would aid communism, cause stifling confusion with effective efforts for peace, and ultimately increase the chances for that everdreaded war of total annihilation, however unintended all this may be.

Anyway, we will first examine the students' responses to questions directly connected with pacifism and military service; certain answers to such questions, taken collectively for a given individual, but that way only, can depict a pacifist or a reactionary. Following these answers will be those to items originally designed for comparing pacifists with non-pacifists, and those to questions used to conceal both the identifications and comparisons; these other items hold much interest in themselves.

Taking the Class of 1960 without the questionnaires, I found that about 36% of its graduates had started ROTC training in the freshman year, and that about 24% received ROTC commissions before, and in a few cases just after, graduation from Dartmouth. We should keep in mind that Dartmouth has Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force units, but also that ROTC at the College is entirely voluntary for the student. However, from each class a number of non-ROTC graduates enroll in Officer Candidate Schools, while still others serve as enlisted men.

The questionnaires showed that 25% of the Class felt that ROTC does not belong at liberal arts schools like Dartmouth; 64% disagreed with this, and the rest were uncertain. On the other hand, 24% thought that pacifist movements and organizations should be suppressed or ignored; 67% disagreed here.

To a statement that war only causes more trouble than it prevents and that war and military buildups should be outlawed, agreement climbed to 54% of the students; 35% definitely differed. However, only 30% felt that war is completely immoral, while 54% disagreed. Unilateral disarmament (by the West or the U. S. independently of the Communists) as a solution to a world crisis found support by only 14% of the returns, and opposition by 83%.

A decisive 64% of the returns held that loyalty to all of mankind should exceed nationalism or patriotism, which was favored by only 28%. But to the statement, "Modern capitalism is harmful to mankind," only 16% agreed while 78% took issue. Seventy percent felt that the U.S. should give more foreign aid; 10% disagreed and 20% were noncommittal.

Most highly controversial was a comment that communism is the greatest menace existing today; the affirmative stood at 47% and the negative at 46%. Sixty-one percent of the respondents agreed that there is little danger of Communist subversion in American institutions of higher learning; 28% disagreed. Fifty-six percent of the students thought that Red China should be recognized by the U.S. and admitted to the United Nations; 33% rejected this idea.

Political preferences among the Seniors were 10% conservative Republican, 27% liberal 6% conservative Democrat, 13% liberal Democrat, 37% independent, and 7% other or unknown. Thirty percent favored more government control of free enterprise; 55% were definitely opposed to such control. Seventy percent felt that high income taxes are unavoidable; 21% disagreed.

The topic of labor unions, without specific reference to individual racketeers, was hotly contested among the returns; 43% held that unions had become a menace to society, while 42% thought they had not. But only 14% felt that socio-economic classes had become too rigidly defined in America, 12% were unsure, and 74% disagreed (I grant that this question is rather vague, as others may be). Most of the students (74%) felt that too much of our conduct is based on conformist convention and tradition.

Thinking that most of our newspapers and magazines were free from any flagrant prostitution of the free press were only 28% of the students, while 59% felt that widespread abuse was taking place. Forty-nine percent thought that the extent of crime in the U.S. was alarming; 31% were not so alarmed, and 20% could not say how they felt. One question posed the strong possibility that materialism is the chief cause of juvenile delinquency; 31% accepted this while 51% disputed the connection; 18% took middle ground. Sixty-eight percent supported the common complaint that the U.S. suffers badly from too much luxury and ease; 22% disagreed.

The matters of authority and responsibility were treated further. Eighty-one percent of the returns expressed the view that we (meaning especially we students) are placing too much blame and responsibility on our leaders and educators, and not enough on ourselves; only 11% took issue here. Sixty-nine percent thought that American children generally need more discipline from their parents than has been the case; 17% took a more lenient view and 14% took a neutral one. Asked whether it had often seemed not only enjoyable, but also profitable and proper to resist the authority of parents and teachers, 56% of the students said yes, 31% said no, and 13% were undecided.

Getting to some rather specific and sensitive areas, the questionnaires had, for example, two items on punishment. Only 31% of the returns agreed with a statement that capital punishment cannot be abolished; 62% implied that it could be. Another statement placed the respondent in the position of somebody conducting or proctoring an examination, and catching a friend in the act of cheating; would his first reaction probably be to report his friend? In 37% of the cases this apparently was true, whereas in 53% of them it was not.

Then there were a few questions on sex and marriage. Sixty-four percent of the group agreed that free love is often justified, with the qualification that the people involved are mature and have strong convictions; 27% still eschewed the idea. Seventy percent assented to a statement that birth control should be actively and universally adopted (and thus increased considerably); opposition was by 18%, and uncertainty by 12%. More evenly divided was the issue of whether or not divorces have been granted too freely lately; 36% felt this was true, 40% disagreed, and 24% were undecided.

Several questions dealt with religion. Ten percent of the students professed to be very religious or devout, 38% somewhat religious, 10% indifferent or unsure, 32% skeptical or agnostic, and 10% atheistic. Forty-six percent agreed with a remark that immortality or the lasting quality of the soul is probably a myth or fancy; 38% definitely believed otherwise, and 16% were uncertain. Is an unreligious person always in trouble? Only 8% thought so, and 86% disagreed. Should religious authority be determined by the individual himself? Ninety percent agreed, and a very small 7% disagreed.

There was also an item on "the most important things in life," which had a dozen possible choices ranging from the most materialistic to the most spiritual or religious, and with five to be chosen and ranked in turn by each student. The most highly rated values by far were creativity and originality, and then kindness and altruism. Other choices, from most to least desired, were scholarship and sophistication, physical fitness, discipline and scientific application, aesthetic qualities (harmony, beauty, order), comfort and security, ambition, spiritual inspiration and reverence, cleverness and sharpwittedness, fame and influence, and wealth. Naturally, there was some overlapping here.

At this point, one might well ask if those students who contributed to the survey were truly representative of today's Dartmouth student body. Actually, it was found that answers came from students with the expected wide variety of personal backgrounds, beliefs, interests, and future plans. Although over 70% of the returns showed favorable reactions to the survey as a whole, completed forms came from less than one-third of the Class. However, I do think that those Seniors who were most concerned about present trends and issues figured well in the analysis, even if the percentages might have been somewhat different coming from the whole Class of 1960 or from all four classes. Anyway I want to thank those of my classmates who did provide answers, and especially those who offered helpful comments and criticisms. I certainly do not blame those who did not make returns, for the hand-outs unfortunately were delayed until shortly before comprehensive examinations, finals, and the third and last G.I. Journal deadline.

Available space allows me little room for comment on the results I have presented with the sometimes-boring statistics. I doubt that many of the findings are original or shocking, but however interesting or uninteresting they may be, I must leave their evaluation to the reader and to the parties concerned. I would urge, though, that we realize what many other surveys have discovered: for instance, that most of the issues are extremely complex and often involve not only conflicts but contradictions; that students tend to become more liberal with formal education but then more conservative after graduation (this brings to mind Robert Frost's well-known observation that he did not want to be radical while young, for fear that it would make him conservative when he became older); that youth, in resurging from its "silent generation" conditions, has lately become very active in polemics and in advancing causes both on the left and on the right; and that pre-college influences are most important, with students thus tending to select their own teachers, groups, and new interests.

As far as my own study goes, I only hope that the survey has proven to be useful and will be followed by better, more precise efforts toward greater understanding of what goes on.

THE AUTHOR, commissioned a 2nd Lt. through the Air Force ROTC last June, is presently on active duty as a student officer at Greenville Air Force Base, Mississippi. He expects to begin his regular duty soon, in the personnel field, with the 4038th Combat Support Group of the Strategic Air Command at Dow Air Force Base, Maine. A resident of Auburn, Maine, he majored in psychology at Dartmouth and was active in student publications.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNine Seniors Speak Out for Individuality and the Intellectual

June 1961 -

Feature

Feature"As Active As They Are Bright"

June 1961 By THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

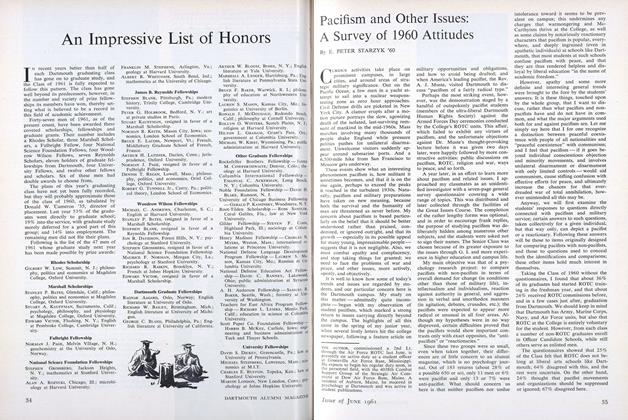

FeatureAn Impressive List of Honors

June 1961 -

Feature

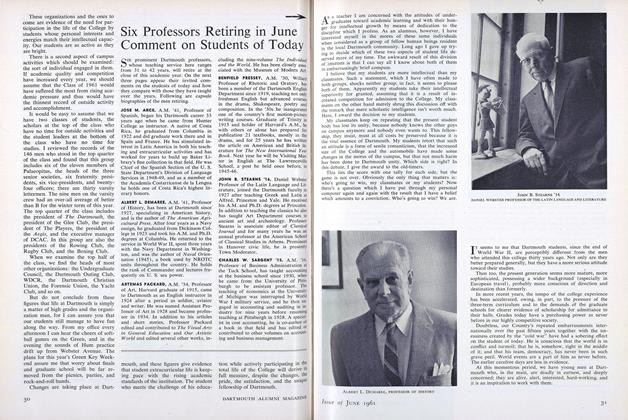

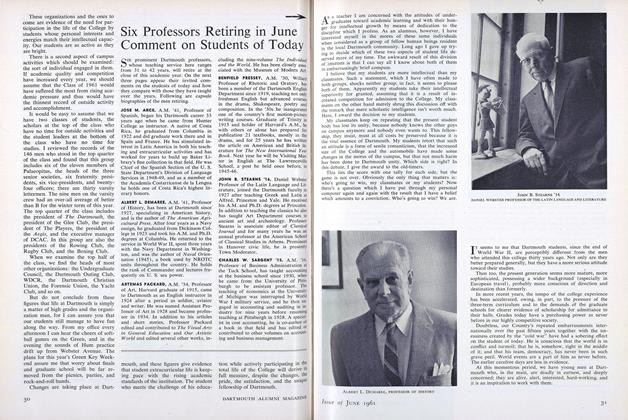

FeatureSix Professors Retiring in June Comment on Students of Today

June 1961 -

Article

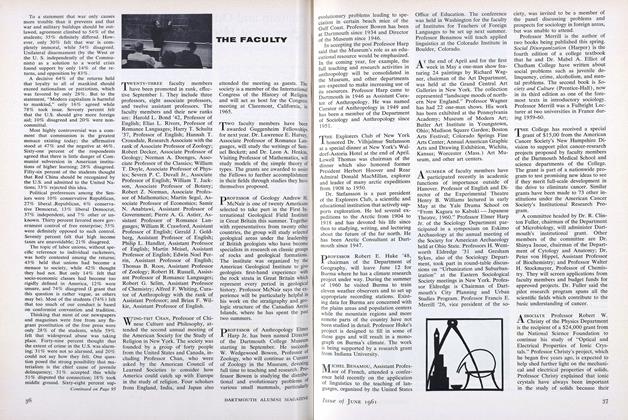

ArticleTHE FACULTY

June 1961 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

ArticleRetiring Tea ...

June 1961

Features

-

Feature

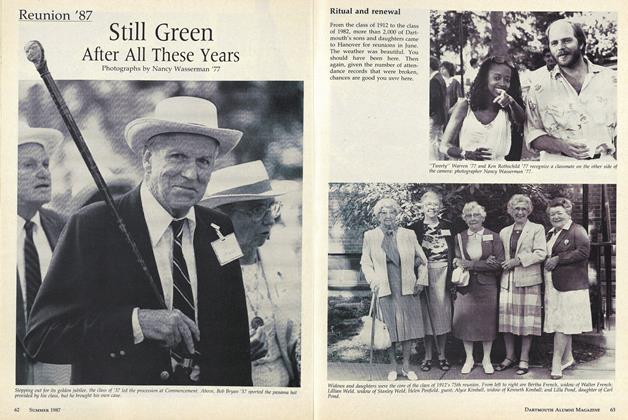

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987 -

Feature

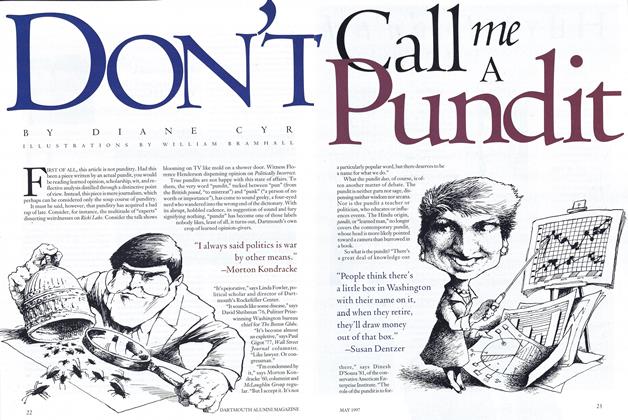

FeatureDon't Call Me A Pundit

MAY 1997 By DIANE CYR -

Feature

FeatureIt’s the Ideas, Stupid

April 2000 By KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81 -

Cover Story

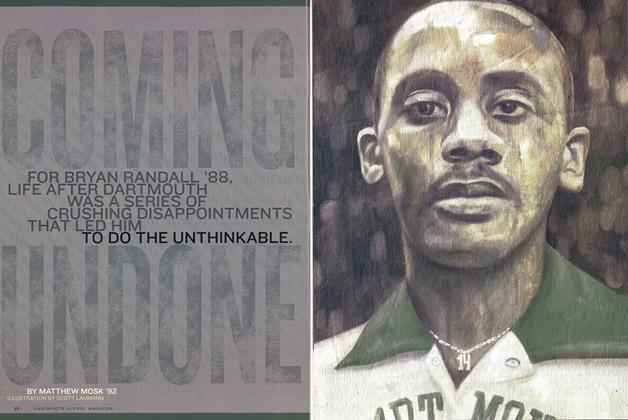

Cover StoryComing Undone

Jan/Feb 2005 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe New Counter Culture

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By RAND RICHARDS COOPER -

Feature

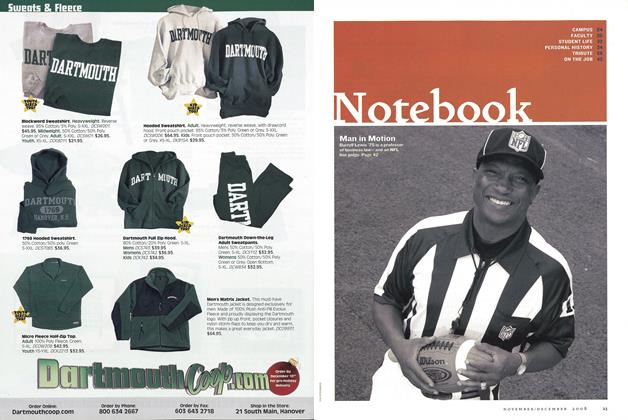

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD