By Hadley Cantril '28. NewBrunswick, N. J.: Rutgers UniversityPress, 1961. 112 pp. $3.00.

This series of three lectures, "Some Political Consequences of Being Human," "The Quality of Political Awareness," and "Pressures and Possibilities," is written by a man who is two-fold a Dartmouth alumnus (A.B. 1928 and Sc.D. 1960). His reputation is world-wide in the field of perception and in social psychology. Human Natureand Political Systems comprises the 1961 Brown and Haley Lectures at the University of Puget Sound, Tacoma (instituted by Frederick T. Haley '35) — a series which includes previous sets of lectures by John Kenneth Galbraith, Merle Curti, and Howard Mumford Jones, among others. One wishes for Dartmouth that the Guernsey Center Moore endowment for lectures were sufficient to allow publication of a similar series.

These lectures cover a lot of ground, literally and figuratively; limitations of space often force the author to cover a chapter in a sentence and a treatise in a chapter. The subjects discussed are the psychological requirements of political systems, the problems of psychological development and inertia, and the emergence and competition of political systems.

One of the great merits of the book is its freshness of approach: a social psychologist perceives the standard problems of political theorists from a new angle. And one of the comforts of the book is that the conclusions of the latter are confirmed by the observations of the former.

A very great deal of experience with foreign nations and with gaining empirical data in foreign countries forms the background of these lectures and gives their conclusions solidity. An abstraction is clinched by a reference to the testimony of a French tool-and die-maker or an Italian farmer or a young engineer in Leningrad or by the author's eye-witness account of some incident in Egypt or Madras.

The result is that this is a spacious little book: it is cosmopolitan and it is urbane. It brings to bear the most modern insights upon one of the oldest of the questions asked by political theory: What is the nature of man? And it ends on a very practical note (p. 103): "Americans must find out from people in other countries in their ownterms what they are, what they are trying to do, what they are trying to become. This can never be done if the primary concern of Americans is to tell other people what they should be doing in order to be more like us."

The book is dedicated to "Tad"; that is to say, Albert Hadley Cantril III, Dartmouth '62.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Cold War and Liberal Learning

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

November 1961 -

Feature

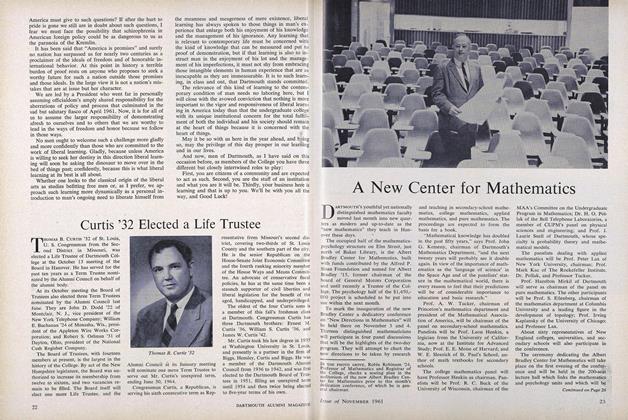

FeatureA New Center for Mathematics

November 1961 -

Feature

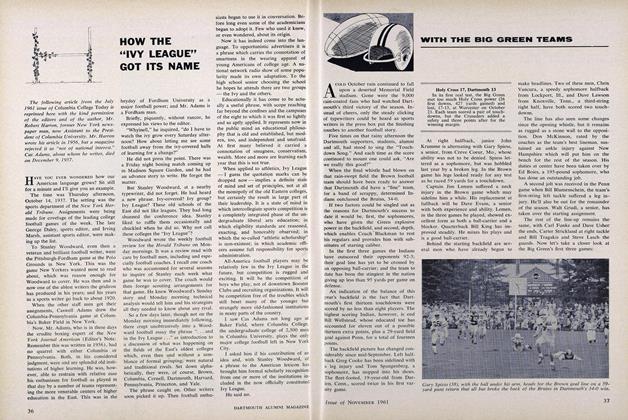

FeatureHOW THE "IVY LEAGUE" GOT ITS NAME

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Meet in Hanover

November 1961 -

Feature

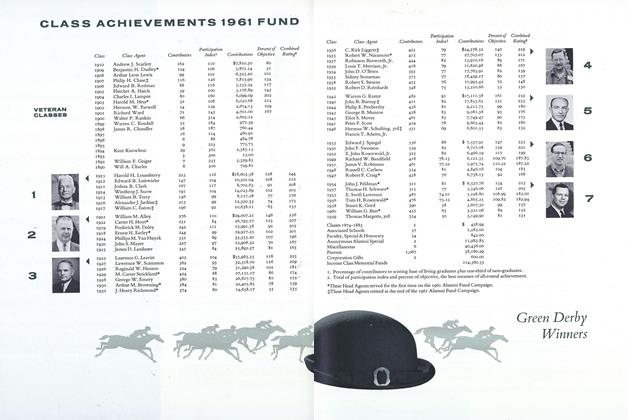

FeatureLASS ACHIEVEMENTS 1961 FUND

November 1961

ARTHUR M. WILSON

-

Books

BooksRAYMOND OF THE TIMES

October 1951 By Arthur M. Wilson -

Books

BooksLA GUERRE D'UN BLEU.

October 1954 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksETHICS IN A WORLD OF POWER: THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF FRIEDRICH MEINECKE

MARCH 1959 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHE LITERARY ART OF EDWARD GIBBON.

June 1960 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksMIDDLING NESS:

APRIL 1966 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

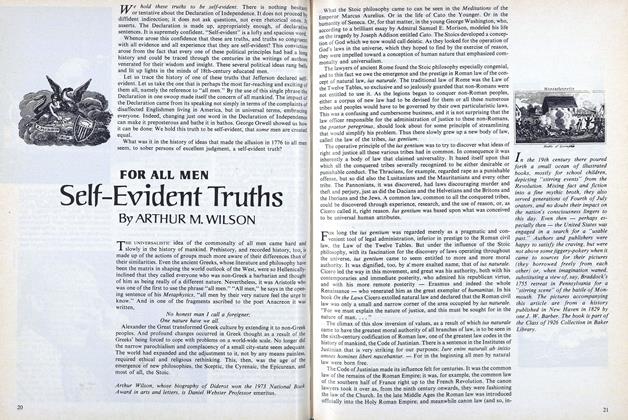

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON

Books

-

Books

Books"Chicago, an Experiment in Social Science Research,"

FEBRUARY 1930 -

Books

BooksA SALESMAN TAKES AN INTEREST.

April 1953 By Albert W. Frey '20 -

Books

BooksCHALLENGE AND PERSPECTIVE IN HIGHER EDUCATION.

MAY 1971 By ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Books

BooksEXPERT BIDDING AT CONTRACT BRIDGE

July 1951 By Frederick Pierce, '01 -

Books

BooksWHAT THE OLD-TIMER SAID: TO THE FELLER FROM DOWN-COUNTRY AND EVEN TO HIS NEIGHBOR—WHEN HE HAD IT COMING

JULY 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksFORECASTING for PROFIT

May 1948 By William A.Carter.