BEFORE SLEEP by Philip Booth '47 Viking, 1980. 78 pp. $12.95; $5.95, paper

You cannot think of nothing without thinking of something. The something Philip Booth gets out of the nothing that perturbs him is this new bulk of rare, clear, hard poems making up from years of feeling, questioning, meditating, and always creating. It is the desire to create which diminishes the diminishment of time. It is from Booth's lifelong speculation that he invites the time-defying properties of poetry.

I said some years ago that Booth was one of the best sea-poets of our time, for the actual sea was ever before him; he knew how to go on it, and how to get off it. But his coast town of Castine, Maine, was also close to forests and pastures, a hinterland, and he wrote about the land, its history, its people, the things people did. Whatever the subject, a sense of seriousness, of profundity, inhabited his poems as it inhabited his mind.

In poetry there is the ancient debate about style and content. Some poets veer toward style, thinking that how it is said is more important than what is said. It may be a bodice, they say, but you notice the embroidery first. Other poets move into meaning as if the meaning comes first, the way the meaning is conveyed second. They consider the. meaning of an individual, for instance, more important and persuasive than the clothes he or she wears. Booth, although he avoids fancifieations of style as excesses in themselves, manages to have it both ways: he possesses, nourishes, and provides the reader with an inimitable style, a style rooted in his primary seriousness and profundity of meaning.

Booth's book is cunningly made of one part of the self often talking to another part of the self. Yet everywhere he maintains a clarity of pure and objective meaning; there is no throwing away of consciousness to dreams, no unbelievable elections of fantasy.

The dialogue with one part of the self talking to another part of the self is maintained throughout the book by poems set in italics juxtaposed to poems set in regular type. It is a kind of musical chiming of ideas, one mode interacting with another to thicken the texture of ideation and feeling and at the same time to enliven and lighten the varieties of considerations with enticing variables, many-faceted. "Nothing I think of is as sure/as my mind's several voices." It is a book of rich affirmations, yet these are balanced by equally rich, suggestive denials. This frame of mind and kind of ventriloquism suggest the tensions of the book and elicits the delectable pleasures one has in reading the new work of Booth.

He harks back to the nothing-something dichotomy:

... Howcan I shape what I feel?Beyond naming names,nothing can help.I learn my limits,I write about what I can;I didn't becomea poet for nothing.

In this play on words he evokes his depths. Indeed, he has become a poet for something. In 1976, that something was a series of remarkable poems in A Mailable Light, and now, in this welcome new volume, he has given us many more expressions of mind and spirit, deep realizations masterfully controlled, and, indeed, some of the best poems of his life and of his generation of contemporary poets.

In his last book he said, "I dug as deep as/My heart could stand." In this book, surveying the whole planet he finds

... nowherebetter, with nothingto lose, than hereto give thankslife takes place. Philip Booth's poems take place to stay.

Holder of a Pulitzer Prize, Bollingen Prize, andNational Book Award, Richard Eberhart continues to write and to teach poetry at Dartmouth and elsewhere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTenure: an academic necessity

April 1981 By A. E. DeMaggio -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureTenure: the tragedy of the slaughterhouse

April 1981 By Peter W. Travis -

Cover Story

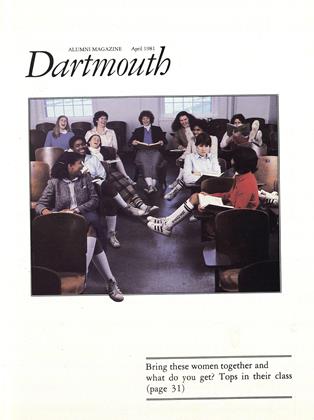

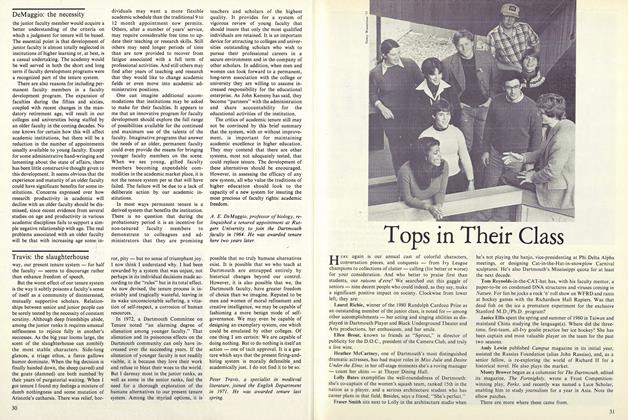

Cover StoryTops in Their Class

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBeethoventorte

April 1981

Richard Eberhart '26

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1954 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, Richard Eberhart '26 -

Books

BooksSPUN SEQUENCE.

July 1962 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Article

ArticleMeditation Two

MARCH 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksSELECTED POEMS.

MAY 1966 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

April 1977 By Richard Eberhart '26 -

Feature

FeatureFish Dinner 1983

OCTOBER, 1908 By Richard Eberhart '26

Books

-

Books

BooksPRACTICAL CANDY MAKING

FEBRUARY 1930 -

Books

BooksTHE LONDON STAGE 1600-1800, PART 4, 1747-1776.

JULY 1964 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN ENGLAND,

April 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22. -

Books

BooksRiver Flowing

December 1975 By LOUIS L. CORNELL -

Books

BooksBIBLIOGRAPHY OF TEXAS,

MAY 1957 By MARCUS A. MCCORISON -

Books

BooksA CRITICAL INTRODUCTION TO ETHICS,

April 1949 By Maurice Mandelbaum '29.