A TRI-MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTINUING THE EDUCATIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACULTY AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGE

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

BEYOND all expectations, the decisions of nearly 69,000,000 Americans registered on November 8 are interesting though somewhat cryptic. Disregarding the local, state, and congressional elections, the presidential election returns raise interesting questions, none of them easily answered.

For some time after the polls closed (hours for most Democrats, weeks for some Republicans) which candidate had won even remained in doubt. Early returns were inaccurately interpreted by some as indicating a near landslide along the lines of those turned in by the New Deal coalition. The majorities in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, and Pennsylvania were not entirely accurate guides to the preferences of voters in the Middle West and West. Kennedy won, but with only a minority of the popular vote and the narrowest percentage margin since 1880.

Thus the question to be answered is not merely why Kennedy won but also why the election was so close. Completely adequate and confirmed answers to these questions must await thorough and detailed analyses of the election returns, the polls, and the surveys of social scientists. Even in decisive elections the problem of explanation is great, involving the sifting and weighing of many factors. In close elections the problems are amplified, the voting patterns of regions, minority groups, urbanites, suburbanites and others being less pronounced.

Since a complete explanation is impossible, the purpose of this article is the less ambitious one of raising and suggesting answers to only a few questions. Why was the Kennedy campaign strategy successful and that of Nixon ineffective in a not unfavorable year for the Republicans? What was the net effect of Kennedy's religion on the results and on the basis of available returns, how did various population groups vote? What was the effect of the television "debates" and how valuable are they as a means of informing the electorate about the candidates and the issues? With the advantage of hindsight but the disadvantage of only partial information, tentative answers to these questions will be formulated.

The Voters Decide

We know that in some elections the results are little affected by the campaigns. The voters make their decisions soon after the candidates are nominated and these choices remain relatively stable. The Eisenhower-Stevenson contest of 1952 fits into this pattern. In other campaigns, events between the conventions and election day are of decisive importance. The 1960 election belongs in this latter group as does, for example, the Truman election of 1948.

To understand this second type of election it is sometimes helpful to construct a chronological profile of voters' preferences at different points of time during the campaign. In addition to the intrinsic interest of such a profile, by relating it to the events of the campaign it may be possible to locate some of the factors which affected the outcome. The following profile is based upon information from the Gallup polls.

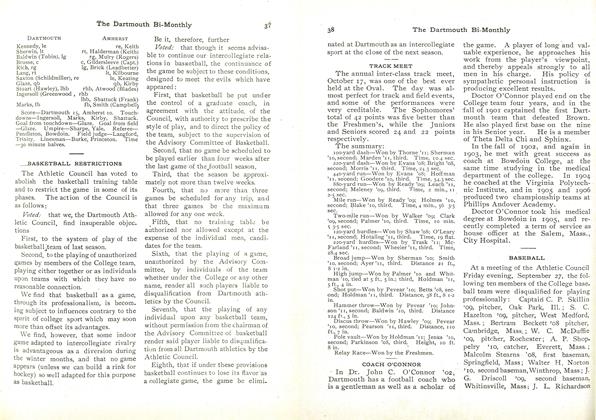

Kennedy-Johnson Nixon-Lodge Aug. 16 47%* 53%* Aug. 31 50 50 Sept. 13 51 49 Sept. 26 49 51 Oct. 11 51 49 Late Oct. 53 47 Nov. 7 51 49 Election 50.1 49.9 * Percentages of those decided.

These figures suggest that it was a very close see-saw contest. It should also be noted that many voters remained undecided during most of the campaign. Gallup reported that 20% of the electorate at the end of August either had not made up their minds or did not feel strongly about their choice. Thus a situation existed in which the campaign could have a decisive effect.

The time at which Kennedy assumed the lead which he never lost (early October) corroborates the view of many observers that the now famous television "debates" were just such a factor. As can be seen, the Kennedy-Johnson lead increased throughout the period of the debates slipping only during the last week or so of the campaign.

In order to formulate a more complete analysis of the election it is necessary to supplement the above information with highly speculative interpretations of each candidate's campaign. In different ways, both Nixon and Kennedy started in the lead. Nixon was the political heir of a highly popular and respected President. He had had eight years of apprenticeship in the executive branch including some experience in handling the problems of the country's foreign relations. His running mate had had similar experience. Peace and prosperity had apparently resulted in feelings of well-being and complacency on the part of the electorate. The solid South had previously been cracked and seemed to be more Republican than ever. The party was united - Eisenhower, Rockefeller, and Goldwater supporting the Nixon-Lodge ticket with varying degrees of enthusiasm. And the polls following the convention indicated that all Nixon had to do was put these advantages to work and hold his lead. Though it was expected that Kennedy would regain some of the votes of Catholics who had strayed from the Democratic fold in 1952 and 1956, Nixon could count on balancing these losses by picking up the votes of normally Protestant Democrats who wanted to prevent the election of a Catholic President.

Kennedy's initial advantage was the normal Democratic majority reflected both in registration figures and congressional elections. An intensive registration drive was organized (by both the Democratic party and the A.F.L.-C.I.O.) in order to translate this advantage into actual votes on election day. His running mate, a Southwesterner, balanced the ticket which thus seemed well designed to recreate the Democratic coalition of the '30s and '40s - urban voters, the South, farmers and western states.

The campaign got off to a slow and rather dull start. Nixon seemed not to want to rock the boat. Whether because he felt he was ahead, or because he had to demonstrate that he was a gentleman contrary to reports about his early campaign style, or because he thought the surest way for a Republican to win was with a repeat of the Eisenhower type of campaign, or because he took his cue from the apparent complacency of the electorate, his early campaign was anything but aggressive. His strongest attack was on the immaturity and inexperience of Kennedy. Without the personality and widespread appeal of Eisenhower he seemed to be trying to win with essentially the strategy of Eisenhower's victorious campaigns.

A review of Kennedy's campaign will suggest why the well-laid plans of Nixon failed. Much of the credit is due, I believe, directly to Kennedy himself. By ably and directly confronting the religious issue early in the campaign, though he was not successful in closing the issue, he probably quieted the doubts of those who, otherwise favorably inclined toward his candidacy, were wavering on the advisability of electing a Catholic to the presidency. Having disposed of this issue as well as he could, he launched an aggressive and liberal campaign designed to define favorably both domestic and foreign policy issues. On domestic issues he forthrightly appealed to majorities in the large urbanized, industrial states. To do this, he had the advantage of running on what is probably the most liberal platform (civil rights, housing, depressed areas, etc.) ever adopted by a major party. Moreover, unemployment in such areas as West Virginia and Pennsylvania undoubtedly helped to create a receptive audience for his program.

Fashioning and successfully executing a broad appeal on foreign policy issues presented more difficult problems. Not only were we not at war, not only was the opposition ticket designed in large measure to create the impression of experienced foreign policy leadership, but the electorate in recent years has considered the Republican Party the safer one in the conduct of our foreign relations. Nevertheless, Kennedy taking a calculated risk, I believe, told the apparently optimistic and complacent American people that under the Republican administration our world position was dangerously declining. Whether he was entirely successful with his seemingly endless repetition of this theme, it gave to his campaign a broad national approach and may have partially neutralized the foreign policy advantages of the Republicans, a difficult feat in a year in which there were few easily observable signs that our national position had seriously slipped due to inadequate leadership. At any rate, he convinced enough of the advantageously distributed electorate that he rather than Nixon could provide the dynamic leadership which he was convincing them was necessary.

The audience-attracting "debates" were probably indispensable for Kennedy's success, not only because of the positive contribution they made to his campaign but also their negative effect on Nixon's. The latter's originally strong point that he, as a result of his experience and maturity, was more qualified for leadership than the young, immature, and even rash Kennedy was not as convincing after the two had confronted each other and alternately dealt with the issues. Whether Nixon or Kennedy "won" the debates or which had the correct policy positions is not the point. In maturity and the ability to handle issues in a tense situation, Kennedy certainly did not look that much worse than Nixon, and at least in the first debate seemed much more confident. Thus Nixon's early strategy was severely damaged if not destroyed because of the vehicle offered Kennedy. The latter, with a huge audience, was able to show the electorate that he was not as he had been pictured; an all-important theme in Nixon's campaign was thus deflated. Furthermore, Kennedy took advantage of his position as the candidate of the party out of power by taking the offensive and defining the issues of the campaign. He thereby put Nixon in a difficult defensive position.

Why did Kennedy lose his rather large lead of late October? Several explanations are available. Possibly the Kennedy campaign was paced to reach its peak too early and as a result he was left without effective campaign material after the "debates." Nixon probably sensed the inadequacy of his approach, shifted his campaign and became more aggressive to good effect. Also, Eisenhower's entry into the fray probably helped, but it was too late. Or perhaps the final afternoon television program, "Dial Dick Nixon," was successful in swinging most of the remaining undecideds in Nixon's direction. Finally, it is possible that the Kennedy lead was not quite as large as it seemed, many of the "undecided" voters being those who were going to vote against him because of his Catholicism.

Voting Patterns and the Religious Issue

The question concerning religion's effect on the vote is one of the most interesting raised during the campaign, which is not to say that it was the most important factor affecting the outcome. The big question since Al Smith's defeat in 1928 - whether a Catholic can be elected President - was, of course, clearly answered in the affirmative. But whether a Catholic Democratic candidate has an advantage or not is a more difficult question which has not been so clearly answered.

The results of the balloting indicate that the issue was a two-edged sword; Kennedy both lost and gained votes as a result of his religious affiliation. Precise measurement of the issue's net effect unfortunately is not possible on the basis of readily available information. Moreover, the information that is available can be interpreted in different ways. My conclusion, cautiously and tentatively offered, is that the religious vote as such probably lost Kennedy more popular votes than it won him; but the location of the pro-Catholic vote in the large states may have been important for Kennedy's victory in the electoral college. In addition, there may have been a pro-minority vote in Kennedy's favor. An identification between members of minority groups, if such existed, could have been one factor in the increased Democratic vote of Jews, Negroes, and others.

It is true that the Democratic vote increased in most predominantly Catholic states, cities, and voting districts. But it is also true that there was little or no increase in others. And Nixon even carried a number of Catholic districts. According to U.S. News and World Report (Nov. 21, 1960), Kennedy received less than a majority in three of nine heavily Catholic urban districts. In one of these, consisting of five middle to upper income precincts in Los Angeles, the Democratic percentage increased over that of 1956 by only 1.5%, from 38 to 39.5.

Information on Kennedy's loss of Protestant Democrats' votes is also not adequate. According to Gallup, one out of four normally Democratic Protestants voted for Nixon. CBS news on election night reported that the Democratic percentage in "Bible belt" areas was 6 to 7% lower than it had been in 1956, the year of the Eisenhower landslide.

But perhaps more important than the above inconclusive evidence is the fact that Kennedy ran well ahead of Stevenson's 1956 showing in almost all areas, not just predominantly Catholic ones. And he did particularly well in those areas and with those groups that Eisenhower, not the Republican party, appealed to in 1952 and 1956. Many who deviated from their normal Democratic voting habits to elect Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956 were rewon by Kennedy. Bear in mind that the latter's percentage of the national popular vote increased 8% over Stevenson's 42% in 1956.

Some data on population group voting are pertinent. The swing back to the Democrats by Negroes is particularly dramatic. For example, in 23 Negro districts in Houston, the 1956 to 1960 shift to the Democrats is from 65% to 87%, in three Tampa districts from an almost even split to 78% Democratic.

The Jewish Democratic vote also increased. Gallup's estimate is that it jumped from 75% in 1956 to 81% in 1960. The returns show that the Democratic vote of union members increased as much as 15 to 20% in some cities. Election analyst Louis Harris reports that in the fourteen largest suburbs Kennedy won 49% of the vote compared with Stevenson's 32% in 1956.

George Gallup's survey results suggest that there were similar voting changes by other groups. From a comparison of survey results with 1956 election figures, he concluded that Nixon was polling fewer votes than did Eisenhower among all population groups. For example, among independents there was a 13-percentage-point decrease; a drop of 15 points among voters 21 to 29 years old; of the women polled, 10% less were supporting Nixon; and among professionals and business men there was a drop of five points. Thus there was a shift back to the Democratic ticket by large numbers of voters in most groups. This suggests that an increased Democratic percentage in Catholic districts is not necessarily or entirely the result of Kennedy's Catholicism. Some of the shift would have occurred anyway.

The conclusion certainly seems justified that Kennedy, even if he were not Catholic, would have rewon many, by no means all, of the Catholic votes Eisenhower had won in 1952 and 1956. Moreover, in the absence of an anti-Catholic vote, Kennedy's victory margin in such states as Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Minnesota might not have been so small and possibly he could have won such states as Tennessee, Kentucky, and Ohio.

The single most important factor was the absence of Eisenhower on the Republican ticket. This negative factor certainly lost more votes for the Republicans than the presence of a Catholic on the Democratic ticket won for them.

The above analysis is highly speculative and based upon insufficient evidence. It is offered as a possible explanation of a Kennedy victory in an election closer than normal. One of the normal victory patterns of recent decades (the '30s and '40s) failed to develop fully because of the slight but significant negative net effect of the religious issue on Kennedy's margin.

The Television "Debates"

The four so-called television "debates" were the only real innovation in campaign technique. This new method of candidate competition and communication with the electorate may prove the most revolutionary political campaign invention of the 20th century. For this reason, it deserves special treatment.

Most commentary on the "debates" has been adverse. Scholars seem to be particularly prone to find fault with them. They argue that these television confrontations are not really debates, that too many subjects are covered too superficially, that the candidates talk past rather than to each other, that the format puts undue emphasis on personal qualities irrelevant to one's ability to perform well the tasks of the presidency, and that candidates are forced to make foreign policy commitments which should never be publicly stated. Many of these points I would agree with. Certainly serious thought and discussion designed to improve the procedures is needed. On balance, however, I think the "debates" had and will continue to have a beneficial effect on our presidential campaigns.

They provide something desirable for the democratic election process which no other currently used campaign technique does. They are an audience-attracting forum (impordiscussion) in which the competing candidates speak at thesame time on the same issues to the same people. As a result of this kind of exposure, voters are more likely to be aware of the alternatives between which they are to decide. An estimated 80,000,000 people (more than voted) had the benefit of seeing and hearing both Kennedy and Nixon create and discuss important issues facing the country. However slight, the differences between the two candidates were made much clearer than they would have been without the debates.

These TV discussions should of course only supplement the regular campaigns, not replace them. Individual speeches on single issues, where candidates can develop their positions at length, are particularly valuable. But they are not adequate by themselves. Studies show that the disadvantage of speeches, in contrast to the "debates," is that they tend to attract only those voters already favorable to the candidate giving the speech. Voters tend to expose themselves only to messages which are consistent with their already formulated preferences.

Certainly TV "debates" compare favorably with other recently introduced techniques. Contrived situations in which the latest techniques designed to sell soap and standardize opinion rather than promote discussion have been increasingly used to take full advantage of the potential irrational reactions of the electorate. The "debates" are not perfect but they are a step in the right direction in the light of the recent emphasis on public relations gimmicks.

Historical Perspective

Looking at the election in its historical context it should be noted that it does not herald the beginning of a new period in the history of American political competition and alignments. Kennedy reforged two-thirds of the coalition which created the Democratic victories of the '30s and '40s. The Republican victories of 1952 and 1956 suggested that this New Deal coalition may have been permanently destroyed. In part it has. But what the Democrats accomplished from 1928 to 1936 - the creation of a Democratic majority coalition - the Republicans have failed to undo. We seem now to be in a fluid transition period in which the voice of the Republicans saying "me too" through an appealing candidate sometimes overcomes the unstable, internally inconsistent Democratic majority coalition. It seems likely that candidate personality, leadership ability, imagination, and policy emphasis will be the dominant issues of presidential campaigns for some time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dollop of Yankee Talk

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureNow They're Flicks, Not Movies, But The Nugget Still Carries On

February 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

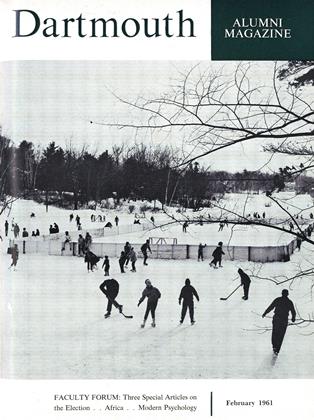

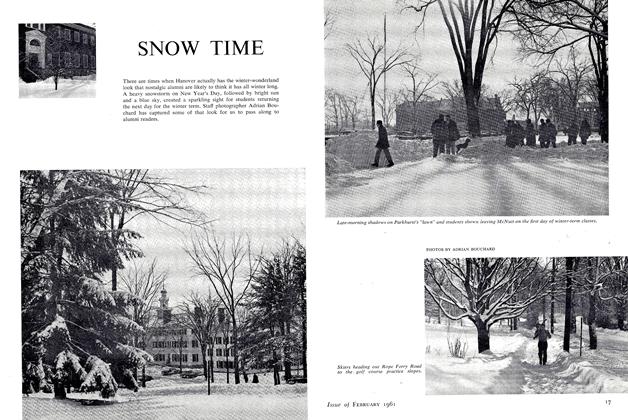

FeatureSNOW TIME

February 1961 -

Article

ArticleProblems of Land Development in the New African Nations

February 1961 By BARRY N. FLOYD,