By Hadley Cantril '28. NewBrunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1960.173 pp. $4.00.

It is oftimes difficult for the average, educated American to picture to himself the masses of the Russian people. When faced with a realistic description of the network of agitation and propaganda, the American incredulously demands to know how the Russians could possibly believe the "big lies" to which they are daily subjected. The aim of Prof. Hadley Cantril's latest book is to show just how this end is attained.

This volume, the format of which to an uncomfortable degree resembles an outline, by reason of the author's having listed his major points numerically, is divided into three parts:

First, Cantril defines what he terms the ".. beliefs, loyalties, and behavior that the Soviets would like to inculcate in the masses." In general, this means that the leaders of the Communist Party wish Soviet citizens to act in conformity with their will. Although this is scarcely new, Professor Cantril must be commended for the manner in which he has attempted to go beyond this generality by specifying in some detail what the will of the party is insofar as the conduct of the Soviet people is concerned. The author supports his observations with numerous quotations from the Soviet press.

Cantril next spells out various assumptions held by Soviet leaders on the nature of man; these range from the fact that Khrushchev, Mikoyan, and company feel that, "... the characteristics and traits of human beings can be transformed in desired directions" to their belief that "...by and large people are incapable of making political decisions and acting effectively on them." One might well question whether the public statements of the regime's leaders do reflect their views of human nature, but nevertheless Cantril's analysis does bring the reader amazingly close to the real Soviet ethos.

The book concludes with a description of some of the obstacles encountered by the party in its attempt to create "the new Soviet man." One finds here an excellent treatment of the "revolts" of Soviet authors and the intellectual restiveness of some segments of the youth. A major problem which Professor Cantril leaves untouched is the intriguing question of what would be the effect of the agitational system on the people were it not bolstered by the party's monopoly of the means of coercion in the society. Until such time as the terror apparatus is completely dismantled - and there seems to be no possibility of this in the near future — it will be impossible to gauge accurately the cumulative effect of agitprop on the population. All that one can really say about the impact of ideology on the Soviet people is that it has a powerful negative effect; i.e., it completely isolates the Russians from competing views from the West.

Despite these minor reservations, the book may well be recommended to those wishing to become better acquainted with the actual operation of Soviet society.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dollop of Yankee Talk

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureNow They're Flicks, Not Movies, But The Nugget Still Carries On

February 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

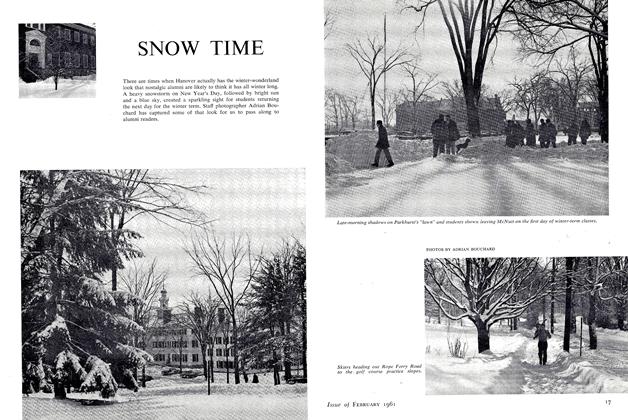

FeatureSNOW TIME

February 1961 -

Article

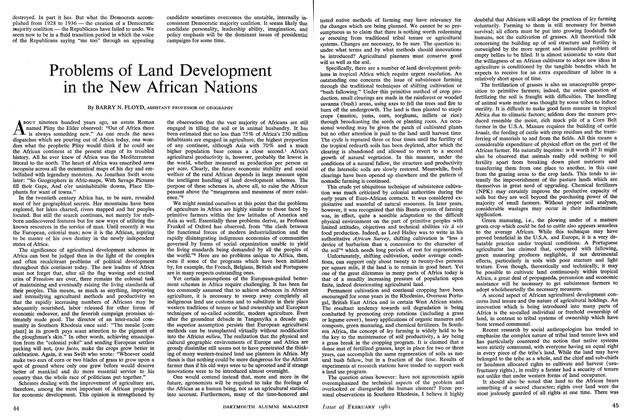

ArticleProblems of Land Development in the New African Nations

February 1961 By BARRY N. FLOYD,

Books

-

Books

BooksWHAT IS LOVE?

May 1958 -

Books

BooksTHE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF RICHMOND,

January 1942 By Everett W. Goodhue '00. -

Books

BooksTHE CHANDALAR KUTCHIN (Technical Paper No. 17).

JULY 1966 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Books

BooksTHE GLORIOUS POOL

April1935 By Malcolm Keir -

Books

BooksTHE SELECTED LETTERS OF GUST AVE FLAUBERT.

May 1954 By RAMON GUTHRIE -

Books

BooksAsking Deep Questions

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Richard Eberhart '26