A Word of Thanks

To THE EDITOR

On our retirement may we use your columns to thank the past and present Dartmouth students whom we have taught for their innumerable kindnesses to us, enabling us to look back on our teaching careers with happiness? And we wish to extend our most sincere good wishes to them all.

Hanover, N. H.

In Praise of Adelbert Ames

To THE EDITOR

I should like to add an evening footnote to Dr. Gliddon's review of Hadley Cantril's The Morning Notes of Adelbert Ames Jr. - a book which I have not yet had the opportunity to read, but which I welcome sight unseen.

I don't know how I first met Professor Ames, for I sat in none of his courses. Perhaps it was through Dr. Gliddon, who prescribed glasses for me at the Dartmouth Eye Institute (and which lasted me without further correction until not too many years ago). Or perhaps it was through Harold Rugg, for Ames, like Goethe, whom he so much resembled, had a lively interest in botany, and he and Harold used to visit the greenhouse where I did most of my work my senior year.

However it was, on the strength — or weakness - of a very slender acquaintance, I sought Professor Ames out in his house. I was perplexed by some world-shaking problem; I forget what it was, but it probably had its origin in our interminable discussions of the Round Table. Professor Ames welcomed me graciously (although he must have had difficulty in placing me) and suggested that we take a walk. He led me over to the woods beyond Occom Pond, and while the winter sun was setting over the Norwich hills, listened patiently to my question. And solved it in one sentence! "Before you say that a thing is good or bad, say that it is." That was all he said: I immediately knew, and knew that this was all I needed to know. That became my philosopher's stone, and has lasted me ever since. I think I ran back in sheer joy to my fraternity house that day, with my new existential prize tucked carefully, so to speak, under my arm.

All of this, by coincidence, came back to me not long ago when I was writing the manuscript of a book on Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., with whom I compared Professor Ames. The comparison may seem superficially far-fetched, but I believe there is a deep affinity between the two, for both men were lovers of God and of phenomenological truth, and especially of the archphenomenon, man. Both were cast in the mold of Spinoza, Goethe, and, as Dr. Gliddon, quoting Horace N. Kallen, says, Leonardo. Is Ames not one of those pioneers whom Sir Julian Huxley is right now calling for to engage in the "gigantic task of synthesis"? I believe that Ames, like Teilhard, sought God, yet at the same time knew Him and loved Him, and that he runs deeper than either Dewey or Huxley, in whom divinity is not recognized as an object of man's knowledge, if I am correct. Under the latter two any synthesis attempted or achieved might very likely become one more vast gnostic error, but Ames, like Teilhard, never lost sight of the flesh, and their witness should be welcomed by all thinking believers in the Incarnation.

Finally, Adelbert Ames had the supreme gift of charity (as I discovered so long ago, by such a happy chance), without which' there can be no good thing, as St. Paul says, and which means no synthesis either.

Washington, D. C.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

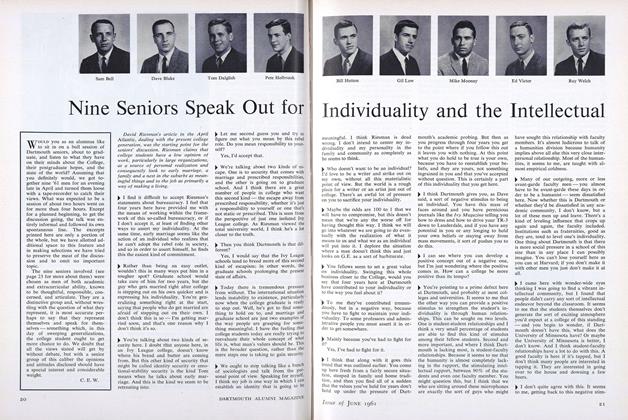

FeatureNine Seniors Speak Out for Individuality and the Intellectual

June 1961 -

Feature

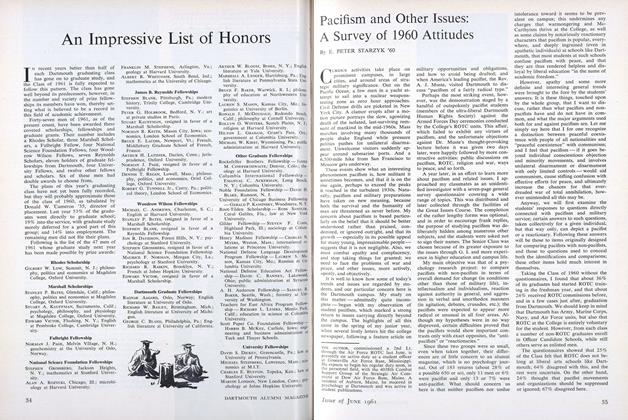

FeaturePacifism and Other Issues: A Survey of 1960 Attitudes

June 1961 By E. PETER STARZYK '60 -

Feature

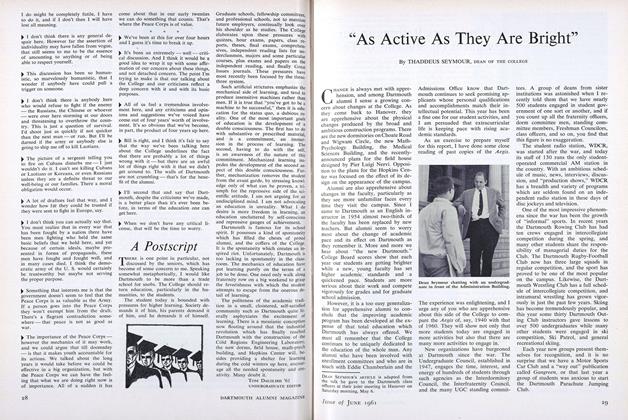

Feature"As Active As They Are Bright"

June 1961 By THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeatureAn Impressive List of Honors

June 1961 -

Feature

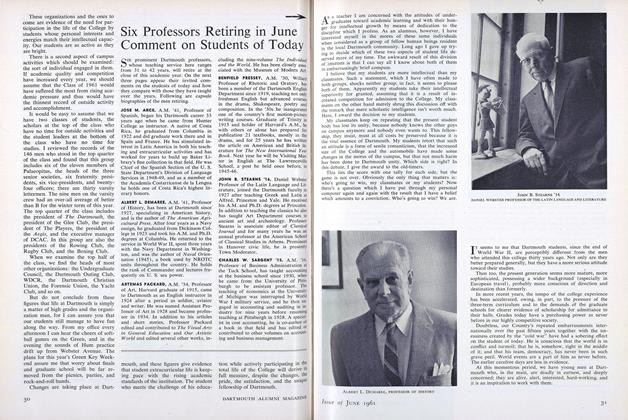

FeatureSix Professors Retiring in June Comment on Students of Today

June 1961 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

June 1961 By HAROLD L. BOND '42