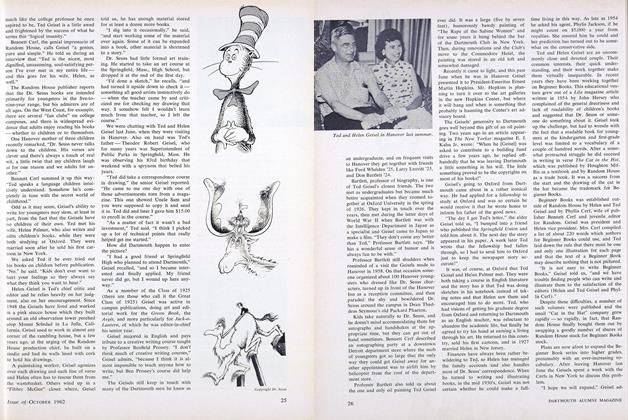

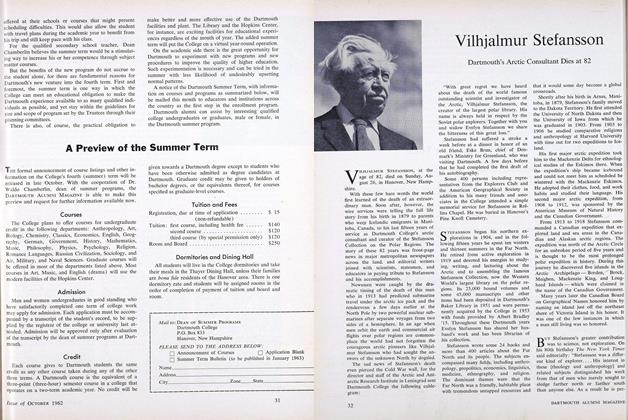

Vilhjalmur Stefansson, at the age of 82, died on Sunday, August 26, in Hanover, New Hampshire.

With these few bare words the world first learned of the death of an extraordinary man. Soon after, however, the wire services were telling the full life story from his birth in 1879 to parents who were Icelandic emigrants in Manitoba, Canada, to his last fifteen years of service as Dartmouth College’s arctic consultant and curator of the Stefansson Collection on the Polar Regions. The story of these 82 years was front-page news in major metropolitan newspapers across the land, and editorial writers joined with scientists, statesmen, and educators in paying tribute to Stefansson and his accomplishments.

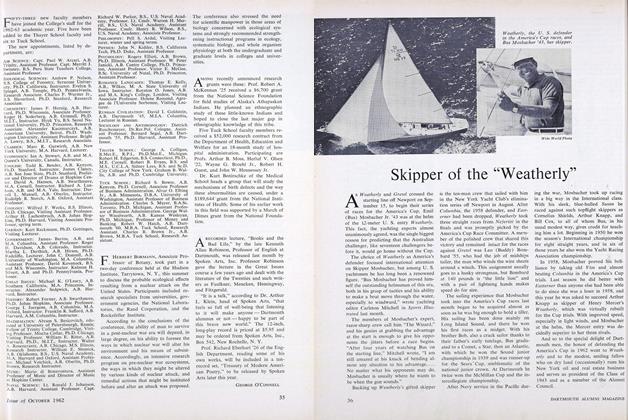

Newsmen were caught by the dra- matic timing of the death of this man who in 1913 had predicted submarine travel under the arctic ice pack and the rendezvous a few days earlier at the North Pole by two powerful nuclear sub- marines after separate voyages from two sides of a hemisphere. In an age when men orbit the earth and commercial air flights over polar regions are common- place the world had not forgotten the courageous arctic pioneers like Vilhjal- mur Stefansson who had sought the an- swers of the unknown North by dogsled.

The sad news of Stefansson’s death even pierced the Cold War wall, for the director and staff of the Arctic and Ant- arctic Research Institute in Leningrad sent Dartmouth College the following cable- gram:

“With great regret we have heard about the death of the world famous outstanding scientist and investigator of the Arctic, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, the creator of the largest polar library. His name is always held in respect by the Soviet polar explorers. Together with you and widow Evelyn Stefansson we share the bitterness of this great loss.”

Stefansson had suffered a stroke a week before at a dinner in honor of an old friend, Eske Brun, chief of Den- mark’s Ministry for Greenland, who was visiting Dartmouth. A few days before that he had completed the first draft of his autobiography.

Some 400 persons including repre- sentatives from the Explorers Club and the American Geographical Society in addition to his many friends and asso- ciates in the College attended a simple memorial service for Stefansson in Rol- lins Chapel. He was buried in Hanover’s Pine Knoll Cemetery.

Stefansson began his northern ex- plorations in 1904, and in the fol- lowing fifteen years he spent ten winters and thirteen summers in the Far North. He retired from active exploration in 1919 and devoted his energies to study- ing, writing, and lecturing about the Arctic and to assembling the famous Stefansson Collection, now the Western World’s largest library on the polar re- gions. Its 25,000 bound volumes and some 45,000 manuscripts and other items had been deposited in Dartmouth’s Baker Library in 1951 and were perma- nently acquired by the College in 1953 with funds provided by Albert Bradley ’l5. Throughout these Dartmouth years Evelyn Stefansson has shared her hus- band’s work and has been librarian of his collection.

Stefansson wrote some 24 books and more than 400 articles about the Far North and its people. The subjects en- compassed many fields, including anthro- pology, geopolitics, economics, linguistics, medicine, ethnography, and religion. The dominant themes were that the Far North was a friendly, habitable place with tremendous untapped resources and that it would some day become a global crossroads.

Shortly after his birth in Arnes, Mani- toba, in 1879, Stefansson’s family moved to the Dakota Territory. He first attended the University of North Dakota and then the University of lowa from which he was graduated in 1903. From 1903 to 1906 he studied comparative religions and anthropology at Harvard University with time out for two expeditions to Ice- land.

His first major arctic expedition took him to the Mackenzie Delta for ethnolog- ical studies of the Eskimos there. When the expedition’s ship became icebound and could not meet him as scheduled he wintered with the Mackenzie Eskimos. He adopted their clothes, food, and work habits and studied their language. His second major arctic expedition, from 1908 to 1912, was sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History and the Canadian Government.

From 1913 to 1918 Stefansson com- manded a Canadian expedition that ex- plored land and sea areas in the Cana- dian and Alaskan arctic regions. The expedition was north of the Arctic Circle for an unbroken period of five years and is thought to be the most prolonged polar expedition in history. During this journey he discovered five islands in the Arctic Archipelago Borden, Brock, Meighen, Mackenzie King, and Loug- heed Islands which were claimed in the name of the Canadian Government.

Many years later the Canadian Board on Geographical Names honored him by naming an island just off the northeast shore of Victoria Island in his honor. It was one of the few instances in which a man still living was so honored.

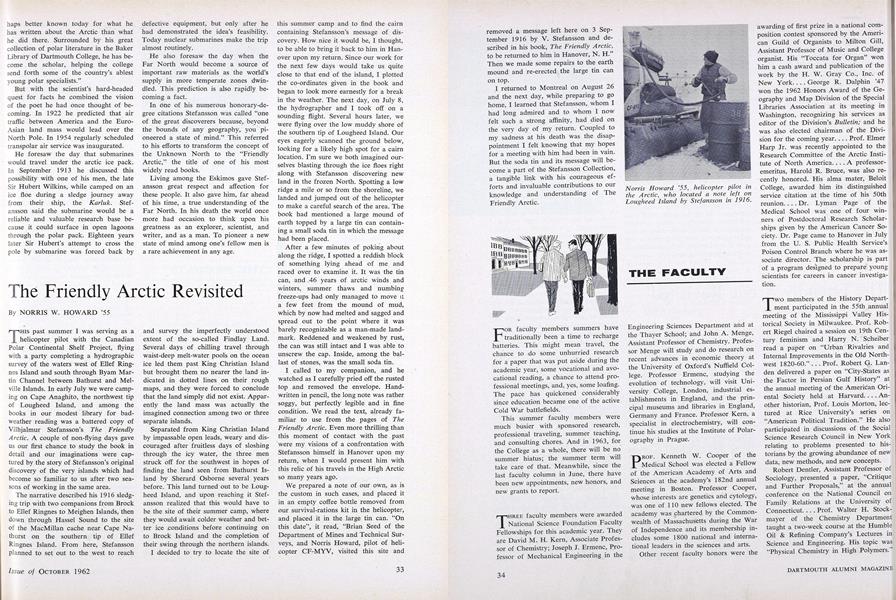

But Stefansson’s greater contribution was to science, not exploration. On his 80th birthday The New York Times said editorially: “Stefansson was a differ- ent kind of explorer. . .. His interest in these [theology and anthropology] and related subjects distinguished his work from that of men who merely sought to sledge farther north or farther south than anyone else. As a result he is per- haps better known today for what he has written about the Arctic than what he did there. Surrounded by his great collection of polar literature in the Baker Library of Dartmouth College, he has be- come the scholar, helping the college send forth some of the country’s ablest young polar specialists.”

But with the scientist’s hard-headed quest for facts he combined the vision of the poet he had once thought of be- coming. In 1922 he predicted that air traffic between America and the Euro- Asian land mass would lead over the North Pole. In 1954 regularly scheduled transpolar air service was inaugurated.

He foresaw the day that submarines would travel under the arctic ice pack. In September 1913 he discussed this possibility with one of his men, the late Sir Hubert Wilkins, while camped on an ice floe during a sledge journey away from their ship, the Karluk. Stef- ansson said the submarine would be a reliable and valuable research base be- cause it could surface in open lagoons through the polar pack. Eighteen years later Sir Hubert’s attempt to cross the pole by submarine was forced back by defective equipment, but only after he had demonstrated the idea’s feasibility. Today nuclear submarines make the trip almost routinely.

He also foresaw the day when the Far North would become a source of important raw materials as the world’s supply in more temperate zones dwin- dled. This prediction is also rapidly be- coming a fact.

In one of his numerous honorary-de- gree citations Stefansson was called “one of the great discoverers because, beyond the bounds of any geography, you pi- oneered a state of mind.” This referred to his efforts to transform the concept of the Unknown North to the “Friendly Arctic,” the title of one of his most widely read books.

Living among the Eskimos gave Stef- ansson great respect and affection for these people. It also gave him, far ahead of his time, a true understanding of the Far North. In his death the world once more had occasion to think upon his greatness as an explorer, scientist, and writer, and as a man. To pioneer a new state of mind among one’s fellow men is a rare achievement in any age.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

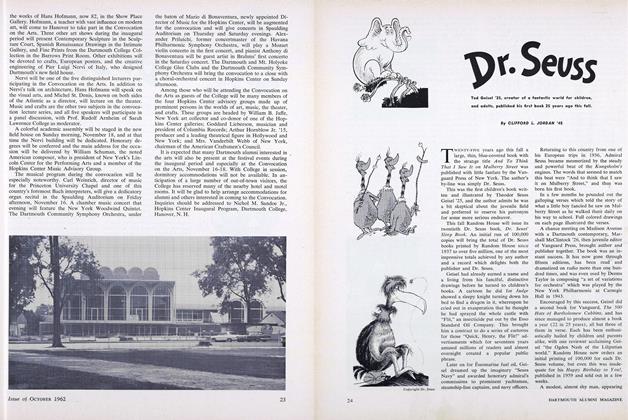

FeatureDr. Seuss

October 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Vanishing Ability To Write

October 1962 By George O’Connell -

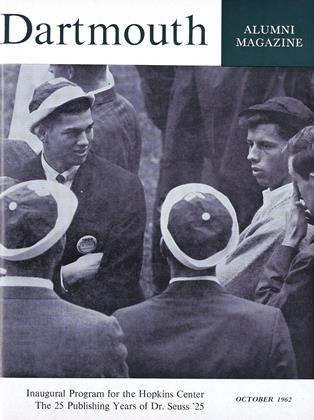

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Big Day Draws Near

October 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTRUSTEES SANCTION A FOURTH TERM

October 1962 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1962 By George O’Connell -

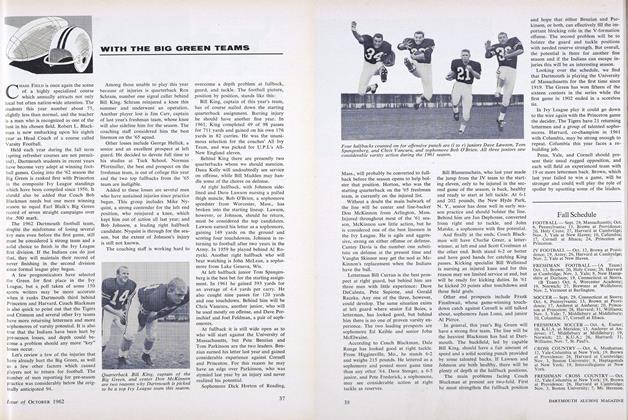

Sports

SportsWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1962 By Dave Orr ’57