This past summer I was serving as a helicopter pilot with the Canadian Polar Continental Shelf Project, flying with a party completing a hydrographic survey of the waters west of Ellef Ringnes Island and south through Byam Martin Channel between Bathurst and Melville Islands. In early July we were camping on Cape Anaghito, the northwest tip of Lougheed Island, and among the books in our modest library for bad- weather reading was a battered copy of Vilhjalmur Stefansson’s The FriendlyArctic. A couple of non-flying days gave us our first chance to study the book in detail and our imaginations were cap- tured by the story of Stefansson’s original discovery of the very islands which had become so familiar to us after two sea- sons of working in the same area.

The narrative described his 1916 sledg- ing trip with two companions from Brock to Ellef Ringnes to Meighen Islands, then down through Hassel Sound to the site of the MacMillan cache near Cape Na- thurst on the southern tip of Ellef Ringnes Island. From here, Stefansson planned to set out to the west to reach and survey the imperfectly understood extent of the so-called Findlay Land. Several days of chilling travel through waist-deep melt-water pools on the ocean ice led them past King Christian Island but brought them no nearer the land in- dicated in dotted lines on their rough maps, and they were forced to conclude that the land simply did not exist. Appar- ently the land mass was actually the imagined connection among two or three separate islands.

Separated from King Christian Island by impassable open leads, weary and dis- couraged after fruitless days of sloshing through the icy water, the three men struck off for the southwest in hopes of finding the land seen from Bathurst Is- land by Sherard Osborne several years before. This land turned out to be Loug- heed Island, and upon reaching it Stef- ansson realized that this would have to be the site of their summer camp, where they would await colder weather and bet- ter ice conditions before continuing on to Brock Island and the completion of their swing through the northern islands.

I decided to try to locate the site of this summer camp and to find the cairn containing Stefansson’s message of dis- covery. How nice it would be, I thought, to be able to bring it back to him in Han- over upon my return. Since- our work for the next few days would take us quite close to that end of the island, I plotted the co-ordinates given in the book and began to look more earnestly for a break in the weather. The next day, on July 8, the hydrographer and I took off on a sounding flight. Several hours later, we were flying over the low muddy shore of the southern tip of Lougheed Island. Our eyes eagerly scanned the ground below, looking for a likely high spot for a cairn location. I’m sure we both imagined our- selves blasting through the ice floes right along with Stefansson discovering new land in the frozen North. Spotting a low ridge a mile or so from the shoreline, we landed and jumped out of the helicopter to make a careful search of the area. The book had mentioned a large mound of earth topped by a large tin can contain- ing a small soda tin in which the message had been placed.

After a few minutes of poking about along the ridge, I spotted a reddish block of something lying ahead of me and raced over to examine it. It was the tin can, and 46 years of arctic winds and winters, summer thaws and numbing freeze-ups had only managed to move it a few feet from the mound of mud, which by now had melted and sagged and spread out to the point where it was barely recognizable as a man-made land- mark. Reddened and weakened by rust, the can was still intact and I was able to unscrew the cap. Inside, among the bal- last of stones, was the small soda tin.

I called to my companion, and he watched as I carefully pried off the rusted top and removed the envelope. Hand- written in pencil, the long note was rather soggy, but perfectly legible and in fine condition. We read the text, already fa- miliar to use from the pages of TheFriendly Arctic. Even more thrilling than this moment of contact with the past were my visions of a confrontation with Stefansson himself in Hanover upon my return, when I would present him with this relic of his travels in the High Arctic so many years ago.

We prepared a note of our own, as is the custom in such cases, and placed it in an empty coffee bottle removed from our survival-rations kit in the helicopter, and placed it in the large tin can. “On this date”, it read, “Brian Seed of the Department of Mines and Technical Sur- veys, and Norris Howard, pilot of heli- copter CF-MYV, visited this site and removed a message left here on 3 Sep- tember 1916 by V. Stefansson and de- scribed in his book, The Friendly Arctic, to be returned to him in Hanover, N. H.” Then we made some repairs to the earth mound and re-erected the large tin can on top.

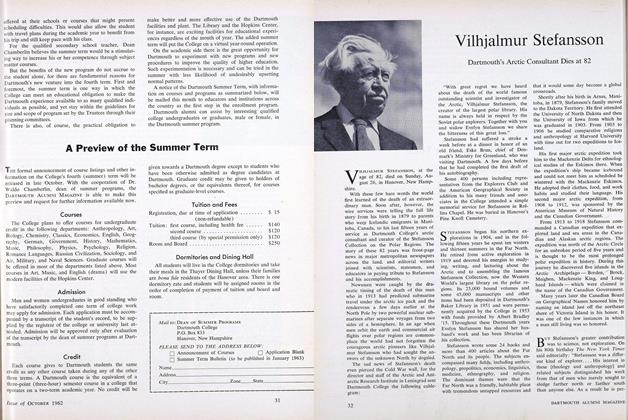

I returned to Montreal on August 26 and the next day, while preparing to go home, I learned that Stefansson, whom I had long admired and to whom I now felt such a strong affinity, had died on the very day of my return. Coupled to my sadness at his death was the disap- pointment I felt knowing that my hopes for a meeting with him had been in vain. But the soda tin and its message will be- come a part of the Stefansson Collection, a tangible link with his courageous ef- forts and invaluable contributions to our knowledge and understanding of The Friendly Arctic.

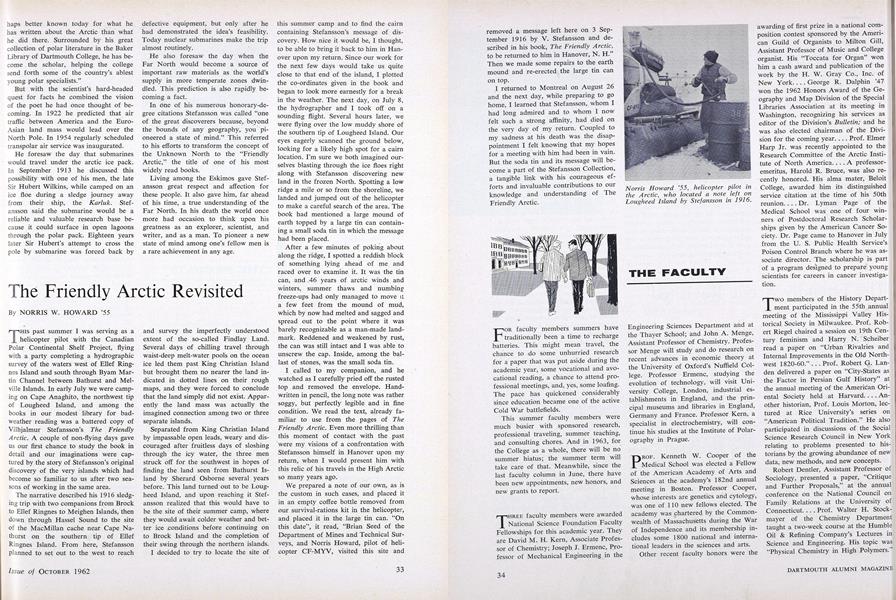

Norris Howard ’55, helicopter pilot inthe Arctic, who located a note left onLougheed Island by Stefansson in 1916.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

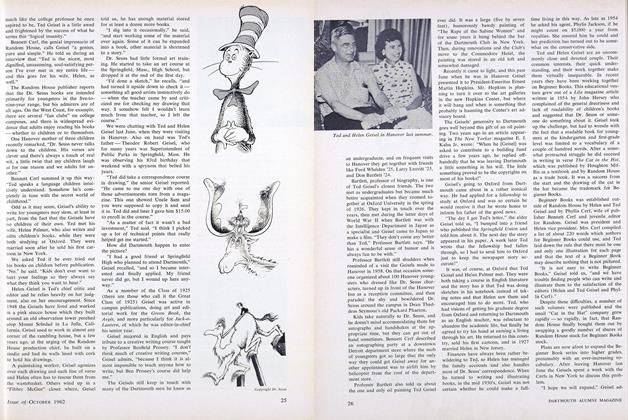

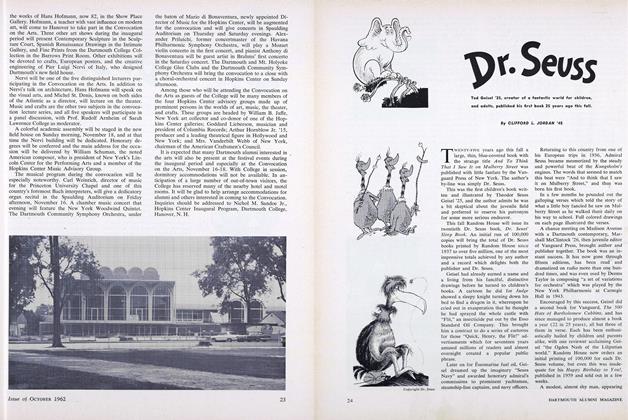

FeatureDr. Seuss

October 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Vanishing Ability To Write

October 1962 By George O’Connell -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Big Day Draws Near

October 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTRUSTEES SANCTION A FOURTH TERM

October 1962 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1962 By George O’Connell -

Sports

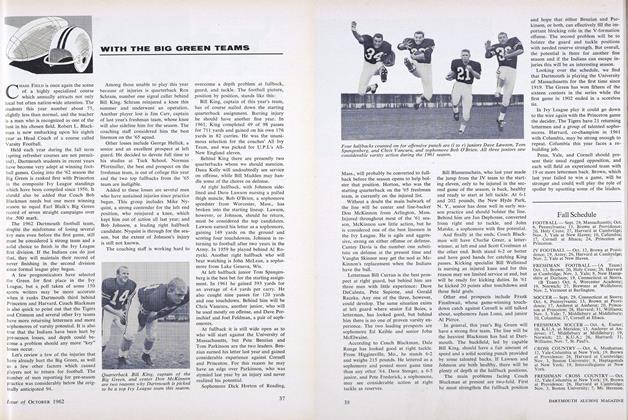

SportsWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1962 By Dave Orr ’57