President Dickey's Convocation Address

OLLEAGUES and Gentlemen of the College:

If the operation of the universe remains on schedule and the enterprises of men stay on course for several more months, come this December Dartmouth will enter its one hundred ninety-fourth year at about the same time as Earth's mechanical emissary begins to eavesdrop on the affairs of Venus.

There is something so gigantically simian about such an interplanetary "operation peephole" that it makes one wonder for a moment whether life elsewhere in any other form could conceivably have developed a propensity for that most human of all our enterprises — education.

Be all that as it may, I am resisting the temptation to start the year off with the thought that our business everywhere is learning. I do this not because I fear that the Class of 1966 would be bothered by such a challenge, but after all you men of the upperclasses may well feel that you would prefer not to have the signals changed on you and that "here" is enough - at least for the moment. So, taking all these into account, I have decided to work out with you and myself a few of the elements in the thought I've used to start the college year for quite a few years now, namely, "Your business here is learning and that is up to you."

Since we are here and not everywhere, let's start with the simple but mighty basic fact that the "here" where we are is not something that any of us did very much to create. Most of us did something about getting here, but the point, which need not embarrass us, is that the here to which we came is largely the work of other lives. The issue that is raised by this fact is not, I think, one of gratitude, but rather whether we are properly here; properly both as to our purposes and as to our willingness in whatever capacity to be a sustaining participant of the place whose presence here is of itself a commitment to something more than the rights of a customer or the responsibilities of an employee. I doubt that any man can helpfully define that more for another man, but I am reasonably sure that it is a very real and a very necessary quality in the life of an institution such as Dartmouth. Some call it dedication, some call it loyalty, others something else. I can only be certain that it went into the making of the here which you and I now enjoy and that it is something a man who is out to learn does well not to take for granted either in himself or in others.

But let us get quickly to the fact that we do not just happen to be here. Dartmouth is here, and each of us is here at Dartmouth because our business, our rightful work, and personal concern, as Webster puts it, is learning.

Most of us would probably stop short of claiming, as has been done for love, that learning conquers all. I personally see no prospect of any such tedious outcome from even the most zealous pursuit of your business here. But if learning has no prospect of conquering all, it assuredly covers all, including, as deans are paid to know, the ways of transgression. Lest that last manifestation of academic candor mislead anyone into unbounded sophomoric zeal for learning, I should add that a distinction is drawn here and elsewhere between a knowledge of sin and its practice.

If it is correct to say that learning covers all, it is also necessary to say that we still have much to learn about the ways of learning. We in education do well to acknowledge that at every level practice and learning theory are still often poles apart. In some situations there sometimes seems to be more jargon than either theory or practice. We cannot get at the intricacies of this problem in public talk but all of us on both sides of any classroom can be more alert and responsive to fresh possibilities for getting forward with the most fundamental aspect of every subject, namely, learning how to learn. And, gentlemen of the student body, permit me to say here, as I shall again in a moment, that although this is an aspect of the business where the professional competence of the teacher is properly at issue, learning to learn is still inescapably up to you. The proposition that no man can "learn another man" anything is not just a rule of grammar; it is a reality of life. Robert Frost did well by this truth, as he does with so many others, when he limited his comment on "self-made men" to asking, "What other kind is there?"

IN a ceremony that attests the institutional quality of Dartmouth and over the years has taken its significance from a sensed unity bounding all the life and work of this campus, we do well to ask what is it in the business of learning here today that gives coherence to our varied, individual efforts? If an institutional sense of purpose gave coherence and was itself an important part of a college education in the past, what's the problem now?

A word of history sets the problem. Richardson tells us that in the early nineteenth century probably nine out of ten Dartmouth graduates entered one of four professions: the law, medicine, theology, or teaching. During this period there was little need or opportunity for these men to do graduate study beyond the baccalaureate degree. This pattern held through most of that century. And in the twentieth century when a growing number of the College's graduates have entered business relatively few until recently went on to advanced study. In these circumstances, the strategy of the historic liberal arts college in meeting the educational needs of the professional and leadership sectors of American society was fairly simple and straightforward.

Likewise, the ancient problem of keeping liberal learning sufficiently comprehensive to be genuinely liberating was relatively manageable for a college until new knowledge and the old order of things both began to explode with disconcerting disregard for the difficulty involved in revising a curriculum. One might almost say that American liberal education in those days did Kipling one better in that "East was East and West was West" but the East was also irrelevant.

In truth, until about the time you men of 1966 celebrated the end of World War II with a screaming entry into Earth's atmosphere, the world of western learning was a rather cozy corner of human experience compared to the planetary, indeed universal, relevance that now bears down on students and teachers alike.

Partly to avoid the rhetorical educational bog where junctures are invariably critical, circles always vicious, and spirals seem only to go downwards, I am going to suggest that the most perplexing problem in undergraduate education today is not in fact the dilemma it is often termed. Indeed, I would go further and assert that one of the principal functions of the institution of the college, today as never before, is to maintain a climate of purpose and program which will protect the student from immaturely concluding that the facts of life in higher education confront him with a dilemma of damning choice as between professional and liberal studies rather than a difficulty that his learning can manage.

I speak, of course, of the fact that an overwhelming and growing majority - seventy percent and upwards — of this student body must be intensively prepared here and now for specialized study beyond the baccalaureate degree if, man by man, you men of Dartmouth are to have in your time a chance at the kind of leadership that over the years has been the justification and pride of this College. On most of the mountains you will wish to climb there is no other way to the top today.

And yet in the same breath one must speak the other fact, and a fact which at the moment a student must take a little more on faith, that unless here and now your learning introduces you to those human experiences that teach a man wherefore he is not "an island unto himself," you will be a poor bet for either the power of any leadership or the most meaningful enjoyment of your life.

The challenge which I invite each of us to welcome is to meet both of these facts of life here at Dartmouth on their own terms.

WE start with the inestimable advantage that Dartmouth has had nearly two centuries of experience in melding the purposes of professional preparation and liberal learning. It is no happenstance that each of her associated schools of medicine, engineering, and business administration was established as a pioneering venture of professional education in America. Nor is it chance that these schools today maintain a more direct and intimate relationship with the purposes and work of liberal learning than is probably to be found on any other major campus. Likewise it was not merely an instinct for the novel (and the difficult) that led Dartmouth to undergird its new doctoral programs with explicit concern for this side of the qualifications and ongoing development of her Ph.D. candidates.

But we should not minimize the difficulty we face. The problem itself has new dimensions and it is aggravated by the range and strength of our academic programs. An institutional sense of purpose as a needed factor of coherence and influence in undergraduate education is paradoxically more at issue in a strong college than in a weak one.

The offering of pre-professional preparation in many different and ever more demanding fields of knowledge is, almost by definition, a disintegrating condition. And it is a force towards the fragmentation of an institution's purpose and program which grows worse the better the work is done. In this respect the situation of the undergraduate college with its pre-professional programs is the opposite of a graduate school. In the latter, institutional coherence is promoted by an intensive singleness of professional purpose, while in the college this very same force expressed in a multiplicity of pre-professional programs is by the nature of things at war with any over-all sense of purpose and coherence in the institution.

Yes, the problem is real, but let the record show that the spread and intensification of pre-professional work at the undergraduate level has brought benefits to the liberal arts college as well as problems. It has done much to make hard work respectable even in the "best circles" on campus and this hard work in turn has often, naturally enough, made the work of learning more rewarding for both teacher and student.

Parenthetically, may I add a footnote at this point. There are other areas besides the academic where being committed to a comprehensive purpose is increasingly difficult but still essential in a first-rate undergraduate college. Although the primary concern of Dartmouth must always and manifestly be the quality of its academic work, this College knows full well that the quality of your learning outside the classroom is also important and is properly a part of your business here. And yet I dare not leave it unsaid that the management of time, choice, and priority is itself to learn the most manly extracurricular art of all - the self-disciplined life.

To return to our main concern, I must be clear with you that even though I believe some academic subjects are painting themselves into the corner by overdoing the preprofessional at unnecessary cost to their historic or potential role as liberal studies, and although I am even more concerned lest this overdoing heedlessly erode the very institutional structure of the college itself, I see no answer for these ills in raising a general hue and cry against preprofessional work in today's colleges. Such work has always been a part of our strong, vital undergraduate colleges and a society whose life and livelihood now depend on ever higher levels of specialized competence is going to pay little heed to anyone running in the opposite direction, however shrill his alarm.

Although I am not among those who find reassurance in the view that there is no great difference between the liberal and the pre-professional purpose in higher education, I, like most of us, have had the privilege of knowing lives which manifest the truth that at their highest and best the liberal and the professional are complementary and reciprocate each other's invigoration. That happy juncture however is only achieved, is it not, by the man who has himself mastered both routes up the mountain?

The boy who as a student in college feels forced to resolve a dilemma by a fateful decision as between these two routes of learning would not be one on whom I would want to put my bet to see things differently as a man.

Most of us are here today because we regard it as no mere bravery to promise each other that Dartmouth will remain committed by heritage of purpose, resourcefulness of program, and the example of each of us to keeping both routes open as complementary parts of any learning entitled to be called higher.

I shall not speak now of significant new programs aimed at keeping faith with that commitment which are taking shape in College councils. I will say that this could be a year of notable fresh forward thrust and it assuredly will be a year in which new opportunities, the hard-won gains of earlier efforts, will measure each of us as only opportunity measures men.

Such opportunities will come to us, individually and as a community, with the opening of the Hopkins Center this fall. Here for the first time this College will have music and drama facilities worthy of the place of these great expressive forces in the work and enjoyment of the liberated life. Here will be opportunities for making both the works and the work of all the arts a part of the daily experience of each of us. Here academic classwork, creative activity, cultural enjoyment, and the fellowship of daily life will come together much as they did in the Agora of ancient Athens. In fine, here at a crossroad of Dartmouth life and work will be both a witness and a unique agency of that comprehensive purpose and that resourcefulness of program to which this College stands committed. The third ingredient of an institution of learning made whole is the example of each.

And this brings us, men of Dartmouth, to what I have said on this occasion before. As members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

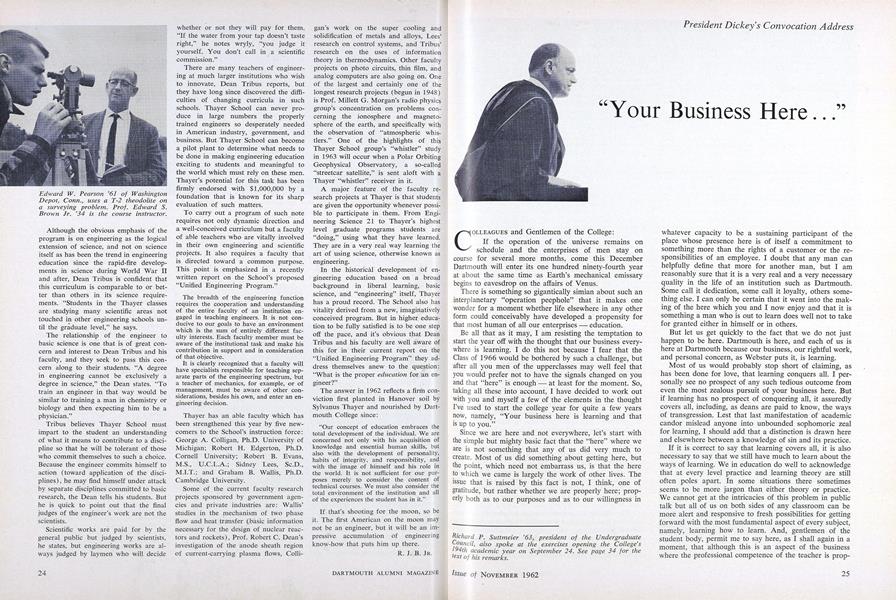

The faculty, in cap and gown, marching into the west wingof the gym for the ceremonies. Remodeling of the wing hasthe basketball court now running north and south, as shown.

A few of the 814 freshmen who occupied a special section at the Convocation exercises in Alumni Gymnasium

Richard P. Suttmeier '63, president of the UndergraduateCouncil, also spoke at the exercises opening the College's194th academic year on September 24. See page 34 for thetext of his remarks.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDefining the Engineer

November 1962 By R.J.B. JR. -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

November 1962 -

Feature

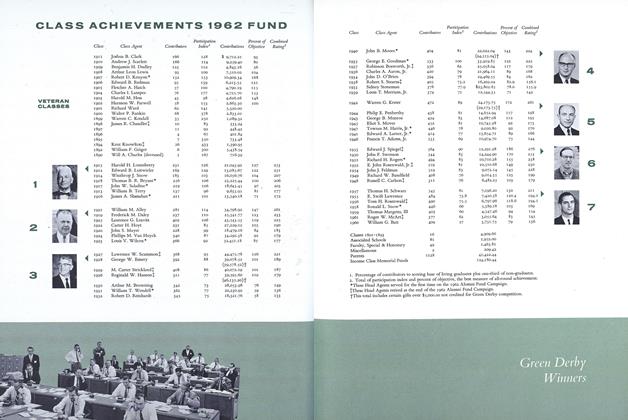

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVEMENTS 1962 FUND

November 1962 -

Feature

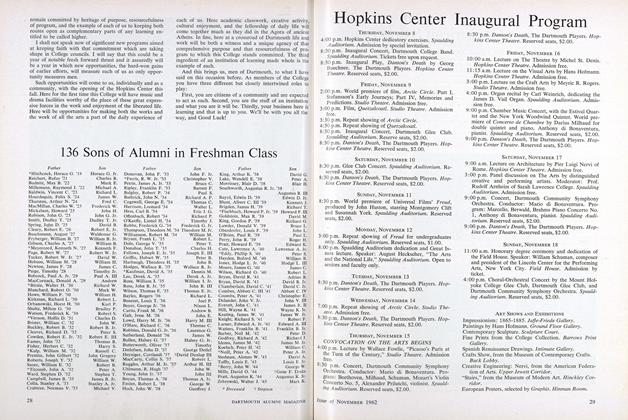

FeatureHopkins Center Inaugural Program

November 1962 -

Feature

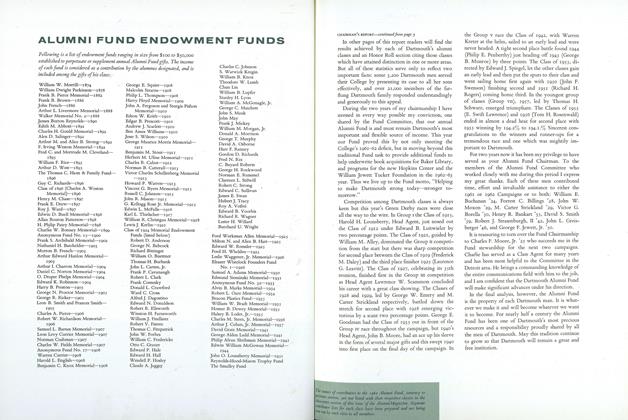

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

November 1962 -

Feature

FeatureA Message from the new Fund Chairman

November 1962

Features

-

Feature

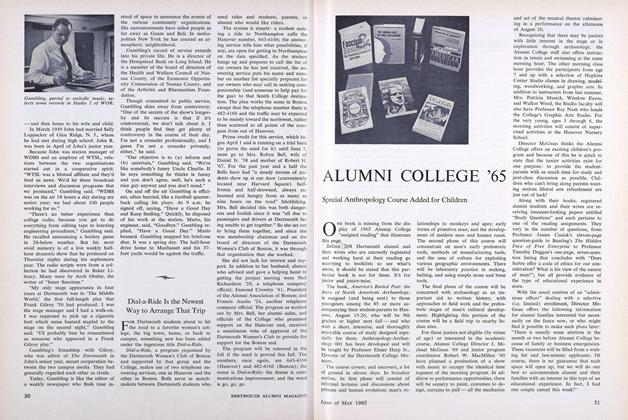

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE '65

MAY 1965 -

Feature

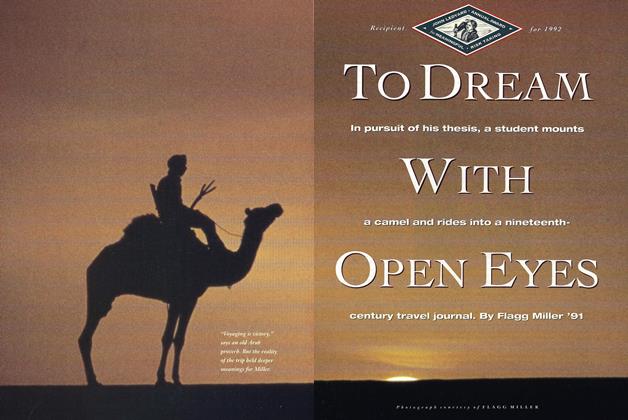

FeatureTo Dream With Open Eyes

APRIL 1992 By flagg Miller '91 -

Feature

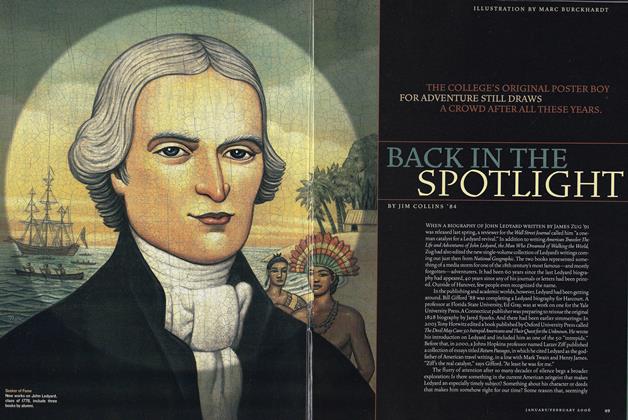

FeatureBack in the Spotlight

Jan/Feb 2006 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Antileadership Vaccine

FEBRUARY 1966 By JOHN W. GARDNER -

Feature

FeatureReport of Twenty-Sixth Alumni Fund

April 1941 By SUMNER B. EMERSON '17 -

FEATURE

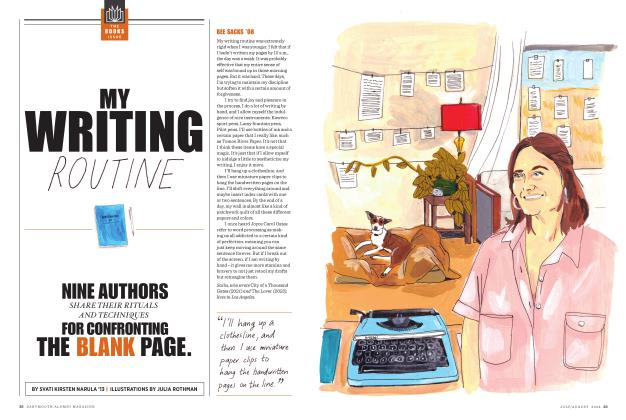

FEATUREMy Writing Routine

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13