VOX

Last spring I was immersed in the lives, and generally not-sohard times, of some 800 people, most of whom I hadn't seen for a quarter of a century.

We were all members of the class of 1963. Several years ago, I agreed to compile a book for our twenty-fifth reunion last June for which each member of the class could write an open-ended essay. Somewhere in all of them, I had hoped, we might uncover the story of a lost cohort of American society.

Our class was not of the '50s and not really of the '60s. We arrived at college in 1959, at the end of the second term of Dwight D. Eisenhower, a popular Republican father figure. We reconvened a quarter-century later at the end of the second term of Ronald Reagan, a popular Republican father figure.

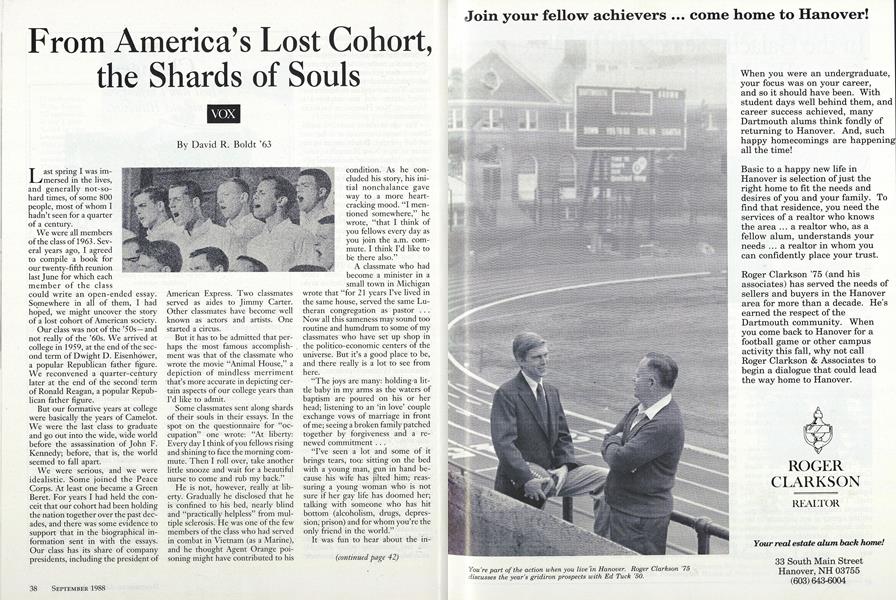

We were serious, and we were idealistic. Some joined the Peace Corps. At least one became a Green Beret. For years I had held the conceit that our cohort had been holding the nation together over the past decades, and there was some evidence to support that in the biographical information sent in with the essays. Our class has its share of company presidents, including the president of American Express. Two classmates served as aides to Jimmy Carter. Other classmates have become well known as actors and artists. One started a circus.

But it has to be admitted that perhaps the most famous accomplishment was that of the classmate who wrote the movie "Animal House," a depiction of mindless merriment that's more accurate in depicting certain aspects of our college years than I'd like to admit.

Some classmates sent along shards of their souls in their essays. In the spot on the questionnaire for "occupation" one wrote: "At liberty: Every day I think of you fellows rising and shining to face the morning commute. Then I roll over, take another little snooze and wait for a beautiful nurse to come and rub my back."

He is not, however, really at liberty. Gradually he disclosed that he is confined to his bed, nearly blind and "practically helpless" from multiple sclerosis. He was one of the few members of the class who had served in combat in Vietnam (as a Marine), and he thought Agent Orange poisoning might have contributed to his condition. As he concluded his story, his initial nonchalance gave way to a more heartcracking mood. "I mentioned somewhere," he wrote, "that I think of you fellows every day as you join the a.m. commute. I think I'd like to be there also."

A classmate who had become a minister in a small town in Michigan wrote that "for 21 years I've lived in the same house, served the same Lutheran congregation as pastor... Now all this sameness may sound too routine and humdrum to some of my classmates who have set up shop in the politico-economic centers of the universe. But it's a good place to be, and there really is a lot to see from here.

"The joys are many: holding a little baby in my arms as the waters of baptism are poured on his or her head; listening to an 'in love' couple exchange vows of marriage in front of me; seeing a broken family patched together by forgiveness and a renewed commitment . . .

"I've seen a lot and some of it brings tears, too: sitting on the bed with a young man, gun in hand because his wife has jilted him; reassuring a young woman who is not sure if her gay life has doomed her; talking with someone who has hit bottom (alcoholism, drugs, depression; prison) and for whom you're the only friend in the world."

It was fan to hear about the investment banker who had finally had it with Wall Street and was now building a house on a Caribbean island. There was an ache of real pain for the classmate had been addicted to alcohol and drugs until 1985. And there was a surprised smile for the classmate who hoped to exploit what he regarded as a life of failure by writing a book, tentatively titled "Feeling Good About Failure."

The closest thing to a recurrent theme was an uneasiness about America's current state of affairs. A successful lawyer from Seattle wrote: "I'm very concerned about the future for our next generation. As a country, we seem to be incapable of dealing with very basic problems in our society. I'm appalled at the lack of quality political leadership. I think if our generation can be faulted it is that we have spent too much time rearing our families and working on our careers and not enough time providing and supporting good political leadership."

Some more encouraging words came from an advertising executive living in Armonk, New York. "Our American system has been so good to me and my family," he wrote, "that I want to start putting back more than I'm taking out. Whether this will be some sort of teaching or full-time volunteer work remains to be seen. I firmly believe our system works best when individuals, rather than government, shoulder the responsibilities. So, in a few years it will be time to step up and be counted."

I'd like to jolt the people of my class with this thought: President Kennedy was our age the year he died.

David R. Boldt is editorial page editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer. This essay is reprinted with permission from Knight-Ridder Newspapers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWelcoming the Loner

September 1988 By Victor F. Zonana '75 -

Feature

FeatureIn the Galactic Search for Intelligence, We May Find Ourselves

September 1988 By Jack Baird -

Feature

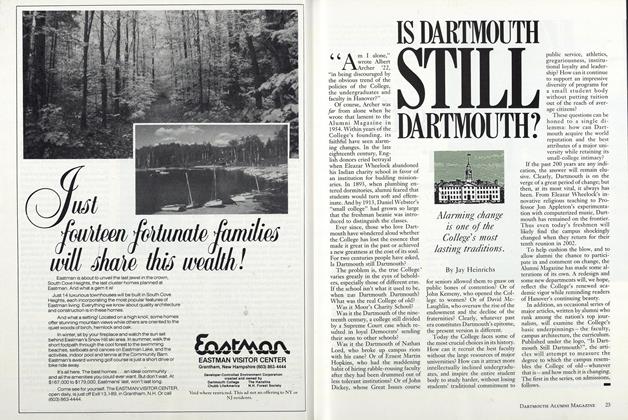

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

September 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

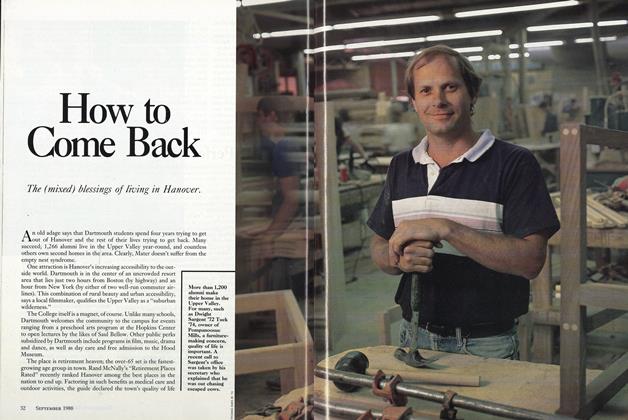

FeatureHow to Come Back

September 1988 -

Sports

SportsFall Sports Preview

September 1988 -

Article

ArticleRush Delayed

September 1988 By Jack Steinberg '88

David R. Boldt '63

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMurray Hitzman '76

March 1993 -

FEATURES

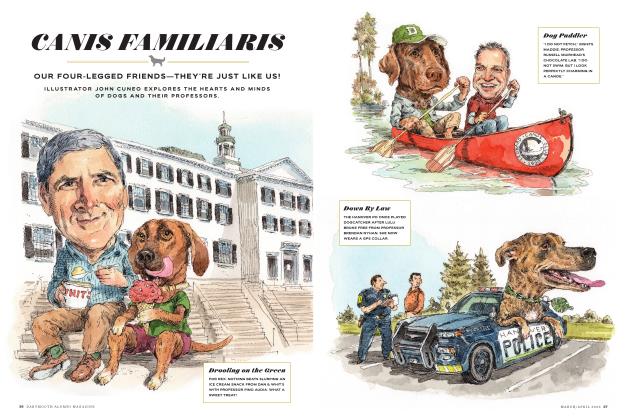

FEATURESCanis Familiaris

MARCH/APRIL 2023 -

Feature

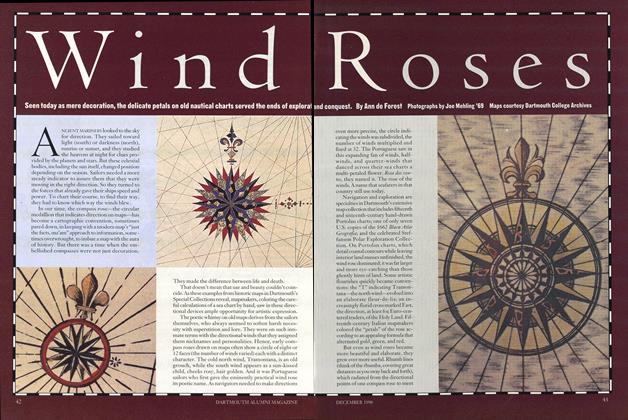

FeatureWind Roses

DECEMBER 1998 By Ann de Forest -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GREEN UP YOUR KITCHEN

Jan/Feb 2009 By JENNIFER ROBERTS '84 -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38 -

Feature

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

OCTOBER 1994 By Varujan Boghosian