Translatedby Frank G. Ryder, M.A. '54. Detroit:Wayne University Press, 1962. 435pp. $8.50.

Presenting medieval literature to the modern reader is never an easy task. Professor Frank Ryder must be congratulated for this elegant, living verse translation of the Middle High German Nibelungenlied. The original text is written in quatrains, the lines riming two by two. The first three lines of each quatrain have four stresses, caesura, three stresses, and a pause; the last line has four stresses, caesura, four stresses. The translator has succeeded in preserving the spirit of this complicated pattern. The quatrains and rime-scheme are retained; the first three lines become traditional iambic pentameter, the last line a hexameter. Professor Ryder has also very wisely transformed the colloquial vernacular of the original into lively, natural, contemporary English, thus avoiding the pseudo-Arthurian or Miltonic jargon which so often masquerades as "poetic rendering" of foreign literature.

In his Introduction, Professor Ryder succeeds in an undertaking no less perilous than the translation. In forty well-written Pages he treats with comprehension and lucidity the fundamental scholarly-critical Problems concerning the Nibehingenlied. This mise au point serves as an excellent vitiation for the general reader, yet also contains stimulating new insights of great value for the professional scholar. By a subtle analysis of certain structural increments (parallelism, correspondence, repetiandthemes (vengeance, courtship and marriage, the journey, etc.), the author demonstrates why we must consider the epic to be a unified, coherent work of artistic proportions and not the haphazard accumulaion of older songs or lays. So too the content, though containing much traditional epic, courtly, and religious maenal, nevertheless reflects the poet's unique assimilation, adaptation, and interpretation of these doctrines. (Our only reservation is that Professor Ryder, who has quite rightly rejected the German Romantic School's approach, on occasion still refers to "traditional Germanic" traits, which, we believe, might just as appropriately have been taken from Latin and French sources.) And, finally, the poem is distinguished by the creation of powerful, intense, individualized characters, who far transcend the usual stereotype.

Many people still think of the Middle Ages as a period distant in time, remote, having nothing to say to us. Professor Ryder's translation of this powerful, "existential" epic, in which "one man's dying brought the death of many men," will help dispel the illusion.

Books

-

Books

Books"The reorganization of Mathematics in Secondary Education"

August, 1923 -

Books

BooksNOTES FROM A BOTTLE FOUND ON THE BEACH AT CARMEL.

APRIL 1964 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksMAS ALLA DEL HORIZONTE

July 1951 By R. Alberto Casas -

Books

BooksSOCIAL ORGANIZATION

January, 1931 By Rees H. Bowen -

Books

BooksUNITED STATES ECONOMIC HISTORY: SELECTED READINGS.

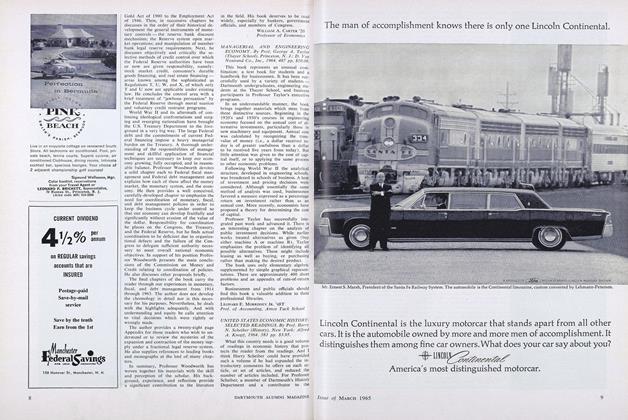

MARCH 1965 By RICHARD S. BOWER -

Books

BooksTHE ANATOMY LESSON AND OTHER STORIES.

July 1957 By ROBERT Y. TURNER