LOVE MATCH AND ARRANGED MARRIAGE, A TOKYO-DETROIT COMPARISON.

NOVEMBER 1967 FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26By Robert O. Blood Jr. '42.New York: The Free Press, 1967. 264 pp.$7.95.

The author of this monograph is a well- known and highly-respected member of that intrepid band of sociologists who, in recent decades, have ventured into the complex and burgeoning field of marriage and family relationships. His previous research has involved the American family, notably that segment living in the Detroit metropolitan area. In the present study, the scene shifts to Tokyo, where the author spent a year as a Fulbright Research Fellow. The work under review is the first intensive investigation into marriage in an Asian country by an American sociologist.

In recent decades, marriage and the family have changed in Japan, along with everything else, and Blood poses two general questions in this connection. (1) What is the differential impact of "arranged" and "love" systems of marital choice? (2) What are the differences (and similarities) between marriage in Japan and the United States? This is not the place to go into detail concerning either the methodology of the study, which is refreshingly simple, or the conclusions, about which the author is modestly tentative. In general, urban, middle-class marriage in Japan is changing from the traditional system, in which marital choice was a contract between families, to one in which the principals play an increasingly important role.

Pursuant to the above hypotheses, Blood examined a number of related questions. Item: What about the genial old Japanese proverb: "Love matches start out hot and grow cold. Arranged marriages start out cold and grow hot." Is this true? Well, sort of. Any such strict dichotomy, the author concludes, is unsound, and the "best" mar- riages involve judicious combinations of "arranged" and "love" elements. Item: What about dating as a way of getting acquainted? fhis happy practice, it seems, is beneficial both in America and in Japan, notably because it helps to counteract the potentially heavy hand of the parents in the latter country. Item: What about outside interests (e.g., foreign travel, higher education) as factors in marital felicity? This seems to depend upon whether these interests are shared by both spouses (good) or not (bad).

In conclusion, Blood remarks that, after expecting to study a family system very different from our own, he found the differences not so great after all. Comparing his sample of 405 Detroit couples and 444 Tokyo couples, he discovered that many interpersonal problems are essentially similar. Such hardy perennials as sex, money, status, boredom, authority, courtesy certain loutish types, belying the famed Japanese courtesy, habitually address their wives as "oi" (hey) or "chotte" (look here) companionship, and sociability are important in both cultures. Such homely little touches are interspersed with more conventional sociological data to give the reader a sound and fascinating series of glimpses into marriage in two societies.

Professor of Sociology

Author of many articles and books aboutthe family, Mr. Merrill is also an authorityon Balzac and the sociological implicationsof French realistic novelists.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

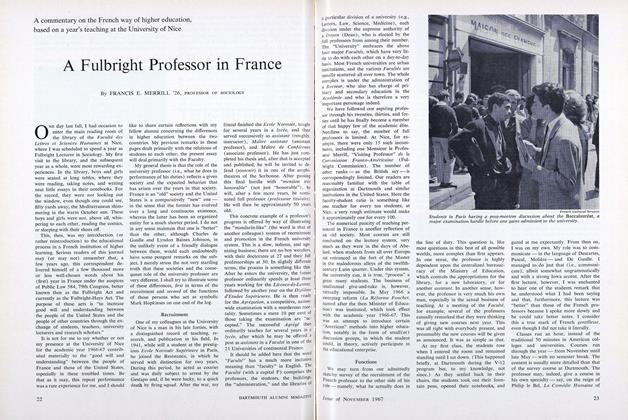

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

November 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26, -

Feature

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

November 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

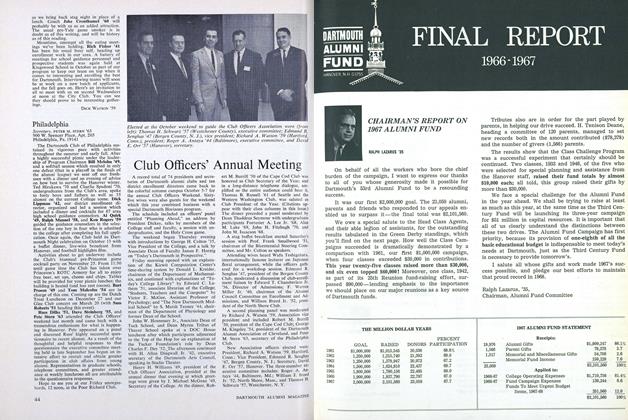

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

November 1967 -

Feature

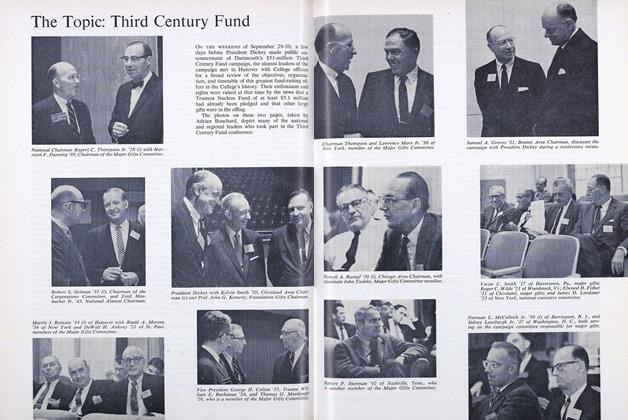

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

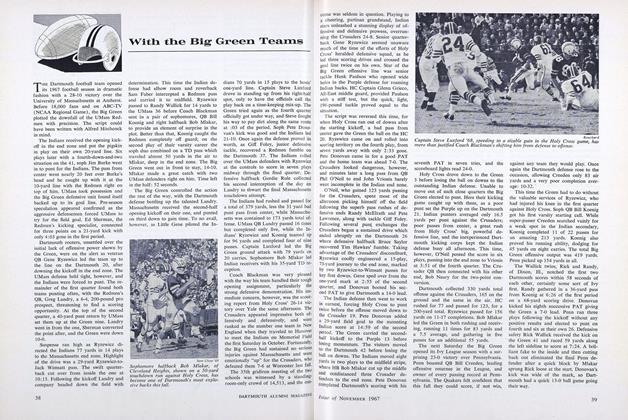

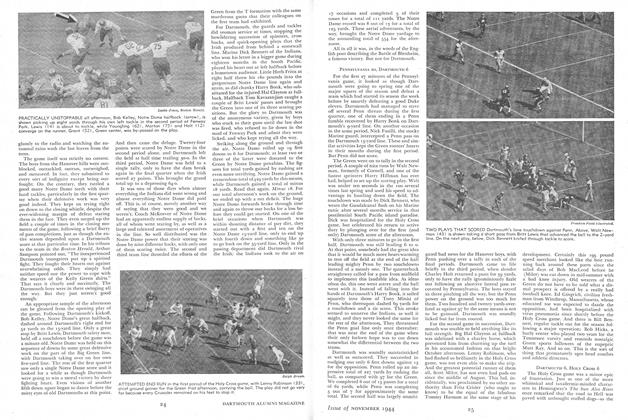

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967

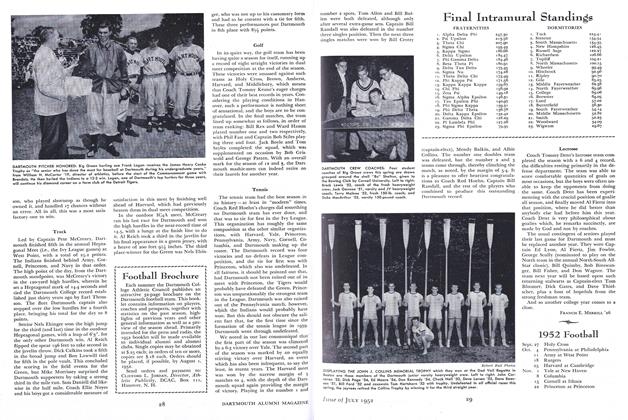

FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26

-

Sports

SportsNOTRE DAME 64, DARTMOUTH 0

November 1944 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsHOCKEY

January 1945 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsBaseball

July 1951 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsSwimming

February 1952 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Sports

SportsFootball Brochure

July 1952 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsTennis

July 1952 By Francis E. Merrill '26

Books

-

Books

BooksROOSEVELT AND THE RUSSIANS

December 1949 By Charles B. McLane '41 -

Books

BooksA Strong and Hungry Spirit

June 1975 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksTHE MEANING OF CULTURE

MARCH 1930 By H. F. West -

Books

BooksTHE LONDON STAGE 1600-1800, PART 4, 1747-1776.

JULY 1964 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksANTICIPATING YOUR MARRIAGE.

November 1955 By RALPH P. HOLBEN -

Books

BooksPROSPECTS FOR PEACEKEEPING.

MARCH 1968 By RICHARD W. STERLING