By William Lee Baldwin. Durham, N. C.: Duke UniversityPress, 1961. 307 pp. $8.75.

This is an intriguing intellectual history of anti-trust policy in the United States. In it Professor Baldwin critically examines the changing economic and social attitudes toward big business from the laissez-faire doctrines of the late-nineteenth century to the recent organizational theories of the corporation. He concludes that economics can make a useful contribution to anti-trust enforcements only when it is recognized that the goals of anti-trust policy must be specified.

Baldwin shows how enactment of the Sherman anti-trust law was motivated less by economic than social and political considerations. It found almost no support among contemporary economists, who were concerned over its interference with the "natural evolution" of industry. Not until the dissolution of the Standard Oil Co. and American Tobacco Co., in 1911, was professional interest fully awakened to the economic implications of the merger movement. Laissez-faire yielded to a recognition of the need for some form of public regulation to preserve competition.

Justification of the merger movement by claims of greater efficiency and stability came under increasing scrutiny during the 1920's. And public concern over the effects of monopoly power on the economic collapse of the 1930's culminated in the T. N. E. C. investigation in the late 1930's. But this monumental inquiry left unanswered most of the important questions about the role of monopoly in the American economy. The Committee concluded with a warning about the threat of big business to democracy, but economists faulted the unusual challenge to influence public policy.

Meanwhile, the concept of "workable competition," formulated by J. M. Clark, offered a more hopeful criterion for anti-trust policy. But this departure from the rigorous tenets of perfect competition was found wanting as an objective guide to action. A more adequate analytical framework awaited the development of the theories of. imperfect competition by Chamberlin, Robinson and others. Schumpeter questioned the useful ness of static equilibrium theory and ad vanced a more dynamic model of the firm Following him, Galbraith delineated a theory of "countervailing power" that eschews the traditional competitive theories. Baldwin reminds us, however, that while the economist can play an important role in perfecting hypotheses, public anti-trust policy is also dictated by other than economic goals

Baldwin acknowledged the useful contributions made recently by social scientists and others in constructing models of the firm as a business organization. These fill the void left by the disappearance of the traditional entrepreneur. But, he argues, they can only supplement - not replace - profit maximization as the guiding principle; this he ranks in importance with competition and laissez-faire.

Professor Baldwin set himself an ambitious task in reviewing and evaluating the voluminous literature on anti-trust policy that has accumulated over the years. This he has successfully woven into an account which gives a new perspective to the evolution of economic policy in this area.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE SHAPE OF DARTMOUTH 1969

April 1962 By C.E.W -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38, -

Feature

FeatureWho will pay—and how?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTPC: MASTER PLANNER

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Role for the Alumni?

April 1962 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26, -

Feature

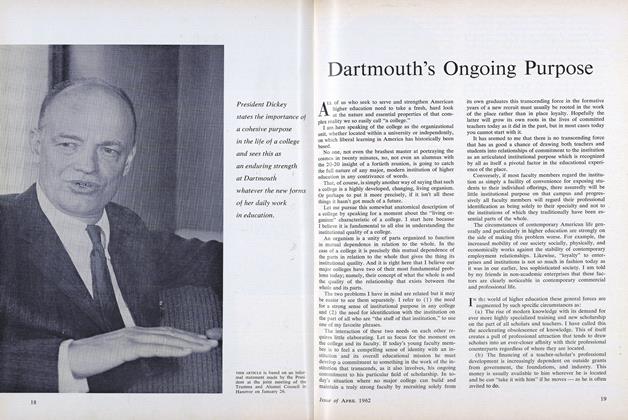

FeatureDartmouth's Ongoing Purpose

April 1962

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE MOTIVES OF NICHOLAS HOLTZ

March 1936 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksTHE DOCTOR OF MAGIC

June 1947 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksOHIO AN ARCHITECTURAL PORTRAIT

October 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksLaw of the Jungle

NOV. 1977 By JOHN S. RUSSELL JR. '38 -

Books

BooksCIVIC RIGHTEOUSNESS AND CIVIC PRIDE

January 1915 By Newton Marshall Hall -

Books

BooksAn Attendant Lord

November 1976 By R.H.R.