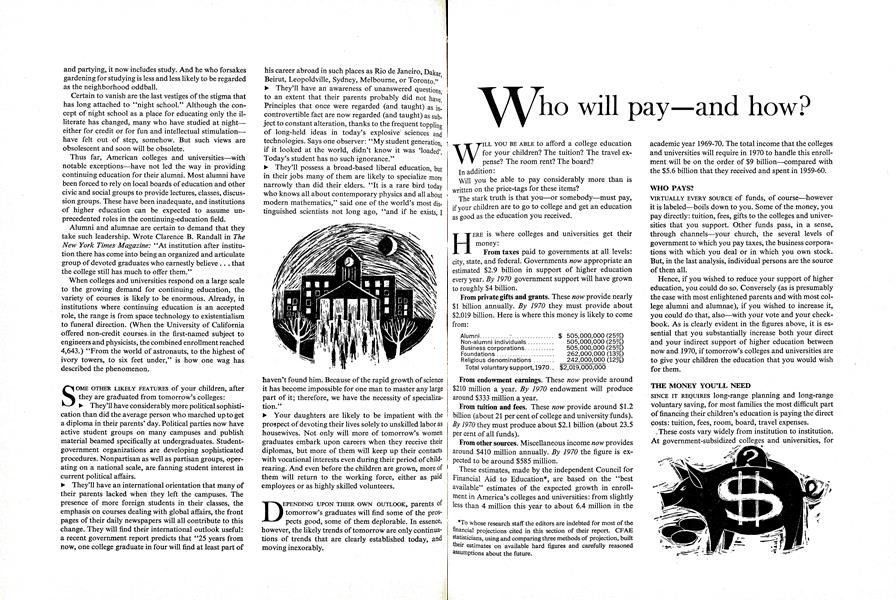

WILL YOU BE ABLE to afford a college education for your children? The tuition? The travel expense? The room rent? The board?

In addition:

Will you be able to pay considerably more than is written on the price-tags for these items? The stark truth is that you—or somebody—must pay, if your children are to go to college and get an education as good as the education you received.

HERE is where colleges and universities get their money:

From taxes paid to governments at all levels: city, state, and federal. Governments now appropriate an estimated $2.9 billion in support of higher education every year. By 1970 government support will have grown to roughly $4 billion.

From private gifts and grants. These now provide nearly $1 billion annually. By 1970 they must provide about $2,019 billion. Here is where this money is likely to come from:

Alumni $ 505,000,000(25%) Non-alumni individuals 505,000,000 (25%) Business corporations 505,000,000 (25%) Foundations 262,000,000 (13%) Religious denominations 242,000,000 (12%) Total voluntary support, 1970.. $2,019,000,000

From endowment earnings. These now provide around $210 million a year. By 1970 endowment will produce around $333 million a year.

From tuition and fees. These now provide around $1.2 billion (about 21 per cent of college and university funds). By 1970 they must produce about $2.1 billion (about 23.5 per cent of all funds).

From other sources. Miscellaneous income now provides around $410 million annually. By 1970 the figure is expected to be around $585 million.

These estimates, made by the independent Council for Financial Aid to Education*, are based on the "best available" estimates of the expected growth in enrollment in America's colleges and universities: from slightly less than 4 million this year to about 6.4 million in the academic year 1969-70. The total income that the colleges and universities will require in 1970 to handle this enrollment will be on the order of $9 billion—compared with the $5.6 billion that they received and spent in 1959-60.

WHO PAYS?

VIRTUALLY EVERY SOURCE of funds, of course—however it is labeled—boils down to you. Some of the money, you pay directly: tuition, fees, gifts to the colleges and universities that you support. Other funds pass, in a sense, through channels—your church, the several levels of government to which you pay taxes, the business corporations with which you deal or in which you own stock. But, in the last analysis, individual persons are the source of them all.

Hence, if you wished to reduce your support of higher education, you could do so. Conversely (as is presumably the case with most enlightened parents and with most college aiumni and alumnae), if you wished to increase it, you could do that, also—with your vote and your checkbook. As is clearly evident in the figures above, it is essential that you substantially increase both your direct and your indirect support of higher education between now and 1970, if tomorrow's colleges and universities are to give your children the education that you would wish for them.

THE MONEY YOU'LL NEED

SINCE IT REQUIRES long-range planning and long-range voluntary saving, for most families the most difficult part of financing their children's education is paying the direct costs: tuition, fees, room, board, travel expenses.

These costs vary widely from institution to institution. At government-subsidized colleges and universities, for example, tuition fees for state residents may be nonexistent or quite low. At community colleges, located within commuting distance of their students' homes, room and board expenses may consist only of what parents are already paying for housing and food. At independent (non-governmental) colleges and universities, the costs may be considerably higher.

In 1960-61, here is what the average male student spent at the average institution of higher education, including junior colleges, in each of the two categories (public and private):

Public Private Institutions Institutions Tuition $179 $ 676 Board 383 404 Room 187 216 Total., $749 $1,296

These, of course, are "hard-core" costs only, representing only part of the expense. The average annual bill for an unmarried student is around $1,550. This conservative figure, provided by the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan for the U.S. Office of Education, does not include such items as clothing. And, as we have attempted to stress by italicizing the word "average" wherever it appears, the bill can be considerably higher, as well as somewhat lower. At a private college for women (which is likely to get relatively little money from other sources and must therefore depend heavily upon tuition income) the hard-core costs alone may now run as high as $2,600 per year. ,

Every parent must remember that costs will inevitably rise, not fall, in the years ahead. In 1970, according to one estimate, the cost of four years at the average state university will be $5,800; at the average private college, $11,684.

HOW TO AFFORD IT?

SUCH SUMS represent a healthy part of most families' resources. Hard-core costs alone equal, at public institutions, about 13 per cent of the average American family's annual income; at private institutions, about 23 per cent of average annual income.

How do families afford it? How can you afford it?

Here is how the typical family pays the current average bill of $1,550 per year:

Parents contribute $950 Scholarships defray 130 The student earns 360 Other sources yield 110

Nearly half of all parents begin saving money for their children's college education well before their children are ready to enroll. Fourteen per cent report that they borrow money to help meet college costs. Some 27 per cent take on extra work, to earn more money. One in five mothers does additional work in order to help out.

Financing the education of one's children is obviously, for many families, a scramble—a piecing-together of many sources of funds.

Is such scrambling necessary? The question can be answered only on a family-by-family basis. But these generalizations do seem valid:

Many parents think they are putting aside enough money to pay most of the costs of sending their children to college. But most parents seriously underestimate what these costs will be. The only solution: Keep posted, by checking college costs periodically. What was true of college costs yesterday (and even of the figures in this report, as nearly current as they are) is not necessarily true of college costs today. It will be even less true of college costs tomorrow.

If they knew what college costs really were, and what they are likely to be in the years when their children are likely to enroll, many parents could save enough money. They would start saving earlier and more persistently. They would gear their family budgets to the need. They would revise their savings programs from time to time, as they obtained new information about cost changes.

Many parents count on scholarships to pay their children's way. For upper-middle-income families, this reliance can be disastrous. By far the greatest number of scholarships are now awarded on the basis of financial need, largely determined by level of family income. (Colleges and other scholarship sources are seriously con- cerned about the fact, indicated by several studies, that at least 100,000 of the country's high-school graduates each year are unable to attend college, primarily for financial reasons.) Upper-middle-income families are among those most seriously affected by the sudden realization that they have failed to save enough for their children's education.

Loan programs make sense. Since going to college sometimes costs as much as buying a house (which most families finance through long-term borrowing), long-term repayment of college costs, by students or their parents, strikes many people as highly logical.

Loans can be obtained from government and from private bankers. Just last spring, the most ambitious private loan program yet developed was put into operation: United Student Aid Funds, Inc., is the backer, with headquarters at 420 Lexington Avenue, New York 17, N.Y. It is raising sufficient capital to underwrite a reserve fund to endorse $500 million worth of long-term, lowinterest bank loans to students. Affiliated state committees, established by citizen groups, will act as the direct contact agencies for students.

In the 1957-58 academic year, loans for educational purposes totaled only $115 million. Last year they totaled an estimated $430 million. By comparison, scholarships from all sources last year amounted to only $16O million.

IS THE COST TOO HIGH?

HIGH AS THEY SEEM, tuition rates are bargains, in this sense: They do not begin to pay the cost of providing a college education.

On the national average, colleges and universities must receive between three and four additional dollars for every one dollar that they collect from students, in order to provide their services. At public institutions, the ratio of non-tuition money to tuition money is greater than the average: the states typically spend more than $700 for every student enrolled.

Even the gross cost of higher education is low, when put in perspective. In terms of America's total production of goods and services, the proportion of the gross na- tional product spent for higher education is only 1.3 per cent, according to government statistics.

To put salaries and physical plant on a sound footing, colleges must spend more money, in relation to the gross national product, than they have been spending in the past. Before they can spend it, they must get it. From what sources?

Using the current and the 1970 figures that were cited earlier, tuition will probably have to carry, on the average, about 2 per cent more of the share of total educational costs than it now carries. Governmental support, although increasing by about a billion dollars, will actually carry about 7 per cent less of the total cost than it now does. Endowment income's share will remain about the same as at present. Revenues in the category of "other sources" can be expected to decline by about .8 per cent, in terms of their share of the total load. Private gifts and grants—from alumni, non-alumni individuals, businesses and unions, philanthropic foundations, and religious denominations—must carry about 6 per cent more of the total cost in 1970, if higher education is not to founder.

Alumnae and alumni, to whom colleges and universities must look for an estimated 25 per cent ($505 million) of such gifts: please note.

CAN COLLEGES BE MORE EFFICIENT?

INDUSTRIAL COST ACCOUNTANTS—and, not infrequently, other business men—sometimes tear their hair over the "inefficiencies" they see in higher education. Physical facilities—classrooms, for example—are in use for only part of the 24-hour day, and sometimes they stand idle for three months in summertime. Teachers "work"—

i.e., actually stand in the front of their classes—for only a fraction of industry's 40-hour week. (The hours devoted to preparation and research, without which a teacher would soon become a purveyor of dangerously outdated misinformation, don't show on formal teaching schedules and are thus sometimes overlooked by persons making a judgment in terms of business efficiency.) Some courses are given for only a handful of students. (What a waste of space and personnel, some cost analysts say.)

A few of these "inefficiencies" are capable of being curbed, at least partially. The use of physical facilities is being increased at some institutions through the provision of night lectures and lab courses. Summer schools and year-round schedules are raising the rate of plant utilization. But not all schools are so situated that they can avail themselves of even these economies.

The president of the Rochester (N.Y.) Chamber of Commerce observed not long ago:

"The heart of the matter is simply this: To a great extent, the very thing which is often referred to as the 'inefficient' or 'unbusinesslike' phase of a liberal arts college's operation is really but an accurate reflection of its true essential nature ... [American business and industry] have to understand that much of liberal education which is urgently worth saving cannot be justified on a dollars-and-cents basis."

In short, although educators have as much of an obligation as anyone else to use money wisely, you just can't run a college like a railroad. Your children would be cheated, if anybody tried.

*To whose research staff the editors are indebted for most of the financial projections cited in this section of their report. CFAE statisticians, using and comparing three methods of projection, built their estimates on available hard figures and carefully reasoned assumptions about the future.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE SHAPE OF DARTMOUTH 1969

April 1962 By C.E.W -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38, -

Feature

FeatureTPC: MASTER PLANNER

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Role for the Alumni?

April 1962 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26, -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Ongoing Purpose

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWho will teach them?

April 1962

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA New Look for Reunions

JULY 1966 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May/June 2012 By Anna Schuleit Adv ’05 -

Feature

FeatureCarnival Post-Mortem

March 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMaster of the Game

MAY | JUNE 2017 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

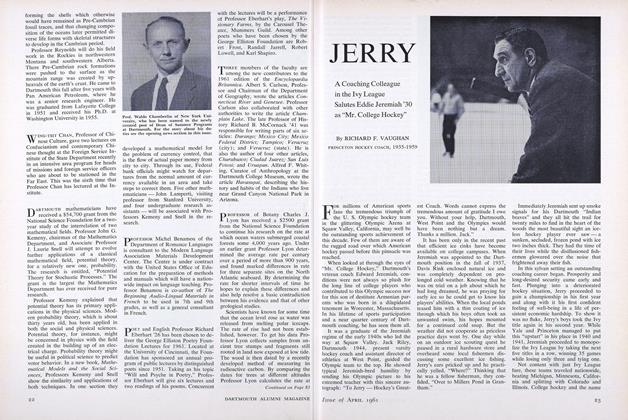

FeatureJERRY

April 1961 By RICHARD F. VAUGHAN