All of us who seek to serve and strengthen American higher education need to take a fresh, hard look at the nature and essential properties of that complex reality we so easily call "a college."

I am here speaking of the college as the organizational unit, whether located within a university or independently, on which liberal learning in America has historically been based.

No one, not even the brashest master at portraying the cosmos in twenty minutes, no, not even an alumnus with the 20-20 insight of a fortieth reunion, is going to catch the full nature of any major, modern institution of higher education in any contrivance of words.

That, of course, is simply another way of saying that such a college is a highly developed, changing, living organism. Or perhaps to put it more precisely, if it isn't all these things it hasn't got much of a future.

Let me pursue this somewhat anatomical description of a college by speaking for a moment about the "living organism" characteristic of a college. I start here because I believe it is fundamental to all else in understanding the institutional quality of a college.

An organism is a unity of parts organized to function in mutual dependence in relation to the whole. In the case of a college it is precisely this mutual dependence of the parts in relation to the whole that gives the thing its institutional quality. And it is right here that I believe our major colleges have two of their most fundamental prob- lems today; namely, their concept of what the whole is and the quality of the relationship that exists between the whole and its parts.

The two problems I have in mind are related but it may be easier to see them separately. I refer to (1) the need for a strong sense of institutional purpose in any college and (2) the need for identification with the institution on the part of all who are "the stuff of that institution," to use one of my favorite phrases.

The interaction of these two needs on each other requires little elaborating. Let us focus for the moment on the college and its faculty. If today's young faculty member is to feel a compelling sense of identity with an institution and its overall educational mission he must develop a commitment to something in the work of the institution that transcends, as it also involves, his ongoing commitment to his particular field of scholarship. In today's situation where no major college can build and maintain a truly strong faculty by recruiting solely from its own graduates this transcending force in the formative years of a new recruit must usually be rooted in the work of the place rather than in place loyalty. Hopefully the latter will grow its own roots in the lives of committed teachers today as it did in the past, but in most cases today you cannot start with it.

It has seemed to me that there is no transcending force that has as good a chance of drawing both teachers and students into relationships of commitment to the institution as an articulated institutional purpose which is recognized by all as itself a pivotal factor in the educational experience of the place.

Conversely, if most faculty members regard the institution as simply a facility of convenience for exposing students to their individual offerings, there assuredly will be little institutional purpose on that campus and progressively all faculty members will regard their professional identification as being solely to their specialty and not to the institutions of which they traditionally have been essential parts of the whole.

The circumstances of contemporary American life generally and particularly in higher education are strongly on the side of making this problem worse. For example, the increased mobility of our society socially, physically, and economically works against the stability of contemporary employment relationships. Likewise, "loyalty" to enterprises and institutions is not so much in fashion today as it was in our earlier, less sophisticated society. I am told by my friends in non-academic enterprises that these factors are clearly noticeable in contemporary commercial and professional life.

In the world of higher education these general forces are augmented by such specific circumstances as:

(a) The rise of modern knowledge with its demand for ever more highly specialized training and new scholarship on the part of all scholars and teachers. I have called this the accelerating obsolescence of knowledge. This of itself creates a pull of professional attraction that tends to draw scholars into an ever-closer affinity with their professional counterparts regardless of where they are located.

(b) The financing of a teacher-scholar's professional development is increasingly dependent on outside grants from government, the foundations, and industry. This money is usually available to him wherever he is located and he can "take it with him" if he moves - as he is often invited to do.

(c) The stronger institutions are in an increasingly stiff competition for the best teacher-scholars. This tends to put a premium on scholarly achievement at the expense in some instances of teaching loads and other services to overall institutional purposes. This and other related factors accentuate the problem on the stronger campuses; for example, whereas President Goheen of Princeton in his 1960-61 Report states that "a researching faculty is the only kind of faculty which is able- out of its own passionate attachment to the search for truth - to infuse in- tellectual curiosity, excitement, and discipline into its teaching in a vital first-hand way," he goes on to say that "the pressures of competition [as to lighter teaching schedules] are telling more severely against us in this respect now than they are in the area of salaries."

I have said that these centrifugal forces are accentuated on the stronger campuses where academic activity is more demanding for both teacher and student. Here at Dartmouth these forces have been building up for at least sixty years, sometime in spurts but always cumulatively as one new strength has called forth another.

And there is a quantitative as well as a qualitative factor in the problem. Bigness in any human enterprise introduces various forms of pluralism. Federalism and departmental specialization in government are reflections of this fact, as is decentralization in the organization and management of our great commercial enterprises. Today's college with a student body of 3000 and a faculty of nearly 300 is inevitably a different organism from the institution of 500 students and 25 teachers on which Dr. Tucker began to build in 1893. The larger institution is almost cer- tain to be more pluralistic in all respects, and pluralism is everywhere the enemy of cohesive purpose. But my thesis is that the vice-versa is equally true; namely, a heightened sense of institutional purpose and identification can be the enemy of the ills of pluralism. This is the point where I believe the problem can be met affirmatively at Dartmouth and throughout the college world. I am sure there is no promise for us in the mere negative rejection of our present size, diversity, or strength.

I shall return in a moment to these problems of purpose and commitment in the nurture and care of institutions, but first let us remember that the living organism of a college, like the rest of us, has great need to be adaptable if it is to serve significantly a rapidly changing society.

It is now a fact that our society and all its constituent parts, e.g., its commercial, professional, and governmental enterprises, are irrevocably dependent on the quality of our higher education. This of itself is a revolutionary change that has happened for the first time in human experience within our lifetime.

At the Alumni Council meeting in June and at many meetings of the Board of Trustees I have talked about the ever-higher demands that our scientific and technologically dominated society is now placing on higher education. I shall not dwell today on that side of Dartmouth's business (a pointed reminder is the fact that about 70% of our graduates now require graduate school training for the kind of leadership life and job they want). There is, however, an underlying consequence of these demands that is relevant to this discussion. I refer to the increasingly competitive world in which these institutions find themselves in their efforts to excel, indeed to survive, as purveyors of competence. This competition focuses on the need of every aspiring institution to get its full share of topnotch teacher-scholars and students, and there is an inescapable reciprocal attraction between these two essentials.

If I had to pick out just one "fact of life" at Dartmouth which I would like to have all Dartmouth men understand better today it would be the present pace of the race in which we have chosen to run - a choice, incidentally, which I'm sure history will say was made at least as far back as Dr. Tucker's day, perhaps even as far back as Nathan Smith's founding of the Dartmouth Medical School in 1797. Certainly ever since 1900 when Dartmouth took the pioneer step of establishing the Tuck School as the first graduate school of business with, as the School's catalogue says, "the standards of a professional school," the die was cast against Dartmouth's long remaining, if even then it was, "a small country college."

And not so very incidentally it should be noted that while a modern America makes new demands on the modern college for drastically sharpened intellectual work on the part of both students and faculty, by and large our society is backing these new demands, particularly in science and technology, with money. For example, much teaching and a substantial portion of our new facilities in the sciences are directly or indirectly financed for us today by the sponsored research grants held by our faculty.

I do not say that this is all good, let alone that it is without dangers and disadvantages, but I do say that as matters stand today we would not even be in the race if it were not for these new resources. For example, the refounded and doubled Dartmouth Medical School is possible only because it now has an annual research program of about one million dollars as compared with one of about $10,000 ten years ago. And so it is with such fine departments as biology and mathematics in respect to staff, facilities, and such new ventures as the doctoral-level programs in molecular biology and mathematics.

Today, as at every point in her history, Dartmouth's primary obligation is to society, a society which she both reflects and helps to fashion. The great reality pervading this obligation is the dynamic, changing character of our society. Today's society demands, especially in the foremost institutions of higher education, a very different level of learning from that which passed current even ten years ago. And it will surely be more so ten years from now. If Dartmouth is to produce men today who will leave their mark on their time as her sons did in days of yore she must meet today's challenge and competition on today's terms, gladly and confidently in the spirit of the Dartmouth family motto, Gaudet Tentamine Virtus: Valor rejoices in contest.

In this spirit she will prevail and her purpose will endure to seek the utmost fulfillment of each man who comes to her in all his potentialities for both the meaningful enjoyment of life and significant service to his society.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE SHAPE OF DARTMOUTH 1969

April 1962 By C.E.W -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38, -

Feature

FeatureWho will pay—and how?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTPC: MASTER PLANNER

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Role for the Alumni?

April 1962 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26, -

Feature

FeatureWho will teach them?

April 1962

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLandauer Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1964 -

Feature

FeatureA Lifetime of Theater

JANUARY 1968 -

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

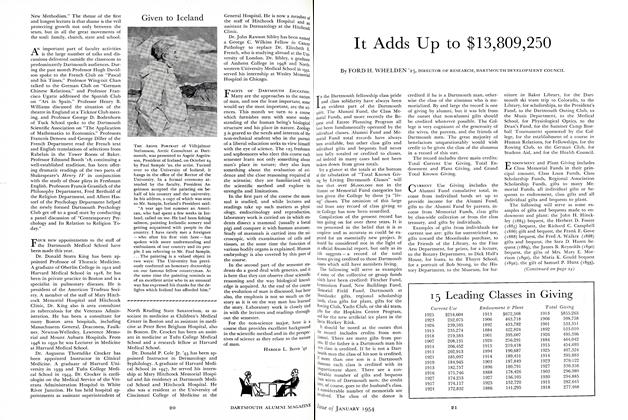

FeatureIt Adds Up to $13,809,250

January 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

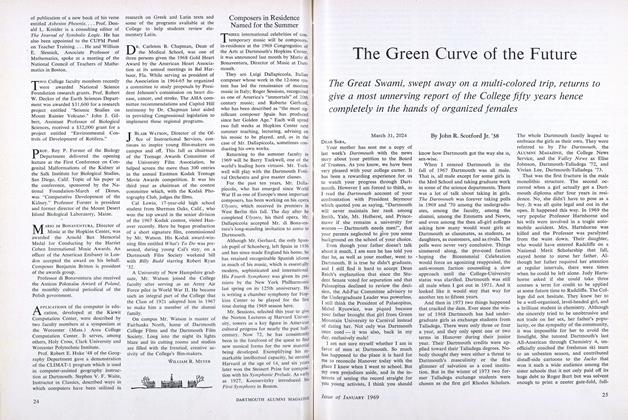

FeatureThe Green Curve of the Future

JANUARY 1969 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

Feature

FeatureStudents in a "Goldfish Bowl" Rise to Debate

MAY 1989 By Ron Lepinskas '89