TO THE EDITOR:

As Dartmouth's only living ex-director of admissions, I was glad to see Mr. Donald McKinlay's letter in your last issue. The persistent myth of individual "well-roundedness" as a supposed criterion for admission dies hard.

The reminder that diversity of inter- ests, skills, and talents in the undergrad- uate body has been an aim of Dartmouth admissions ever since this college took the pioneer step in selective, admissions in 1921 is also useful.

In addition to the references provided by Mr. McKinlay, readers with relatively limited time perspectives might also be referred to President Hopkins' convocation address in 1922, entitled "An Aristocracy of Brains," which produced a considerable dust-up at the time, here and abroad. Statements by President Hopkins, and since 1945 by President Dickey, contain many aspirations to excellence; and, with respect to applicants, excellence hopefully in more than one dimension. But careful readers will find no exhorta- tions by Dartmouth presidents in pursuit of individual "well-roundedness."

In a decade of work as director of admissions, I never heard anyone responsibly connected with admissions at any college espouse "well-roundedness" as a criterion of selection. The late Radcliffe Heermance, Princeton's director of admissions from 1921 to 1950, was credited with the statement almost twenty years ago that the quintessence of "well-roundedness" is the billiard ball. "It takes on a high polish," he is said to have said, "and is easily pushed around."

Few topics have been longer cherished by article-writers, orators and cocktail-party conversation-makers as a straw man for their passionate attack. This is not to say, however, that well-roundedness does not have its earnest advocates. You can find one at any university club bar. (This is one reason why admissions officers shun university club bars.)

Mr. McKinlay, who is one of the most admired in my circle of Dartmouth acquaintances, displays a sophistication in geometry approximately equal to my own when he appears to separate the question of radius from that of circumference. (Don, have you never heard of ?)

What I think Don McKinlay has in mind is a statement which he and I have heard Dartmouth's director of admissions, Eddie Chamberlain, attribute to Dartmouth's articulate coach of track, Elliot B. Noyes '32. This statement was about a particular candidate who showed no especially distinguishable qualifications for admission in a competitive situation. "This," Mr. Noyes is reported to have said, "is a very well-rounded man . . . but with a very short radius."

One wonders indeed who first dreamed up this odd notion that the symbol of desirability for college most resembles the symbol of zero.

One might also recall Mr. Chamber- lain's own satirical piece, published in the Fall 1954 issue of the College BoardReview. Entitled by the Review's editors as "The Chamberlain-Rorschach Master Card," it illustrated, within circular out- lines, the "well-rounded man" as vari- ously viewed by faculty, deans, coaches, and others. The resulting designs took on haunting forms which were distinctly non-spherical.

What do you say that we try to give "well-roundedness" a decent burial somewhere - say, back of Massachusetts Row, not too far from the grave of the splendidly angular Eleazar Wheelock under the new parking lot, if necessary?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDays of Controversy: 1816-1819

June 1962 -

Feature

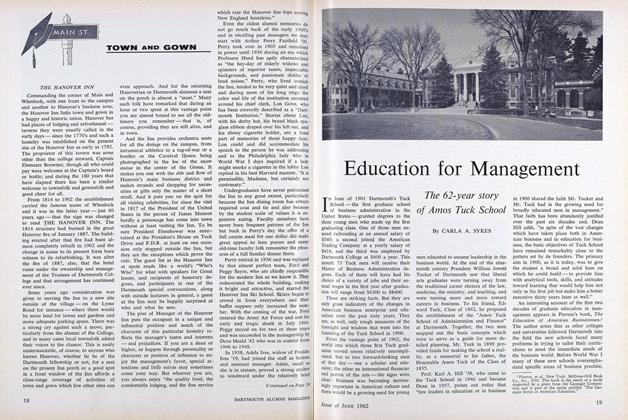

FeatureEducation for Management

June 1962 By CARLA A. SYKES -

Feature

FeatureA College-Church Partnership

June 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

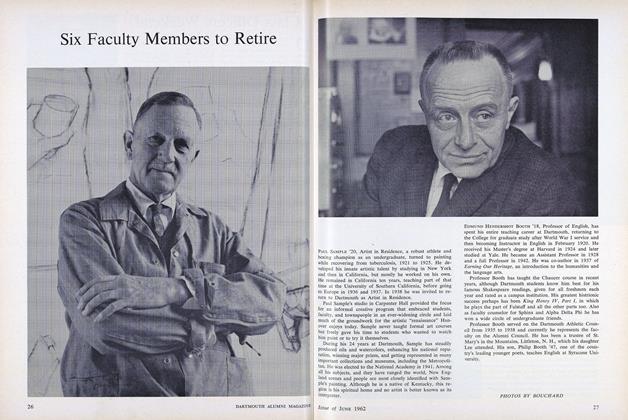

FeatureSix Faculty Members to Retire

June 1962 -

Feature

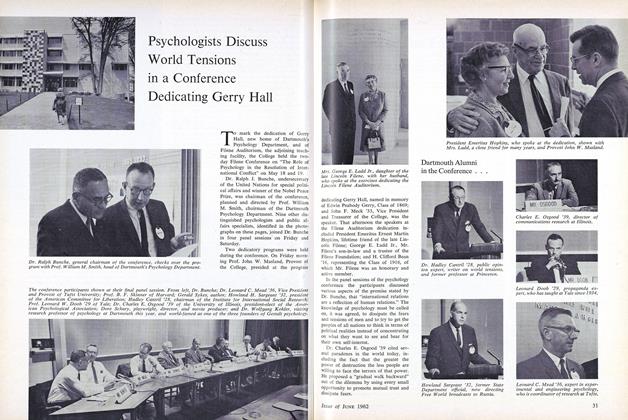

FeaturePsychologists Discuss World Tensions in a Conference Dedicating Gerry Hall

June 1962 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

June 1962 By WILLARD C.WOLFF, WILLIAM T. WENDELL

ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30

-

Article

ArticleHanover Holiday Plus Alumni College

May 1937 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksAN ACCOUNT OF CALLIGRAPHY PRINTING IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

March 1940 By Albert I. Dickerson '30 -

Article

ArticleA DAY WITH A TRAINEE

January 1944 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksNEVER SAY DIET.

November 1954 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Article

ArticleValedictories to Retiring Class Agents

April 1942 By Harvey P. Hood II '18, Albert I. Dickerson '30 -

Cover Story

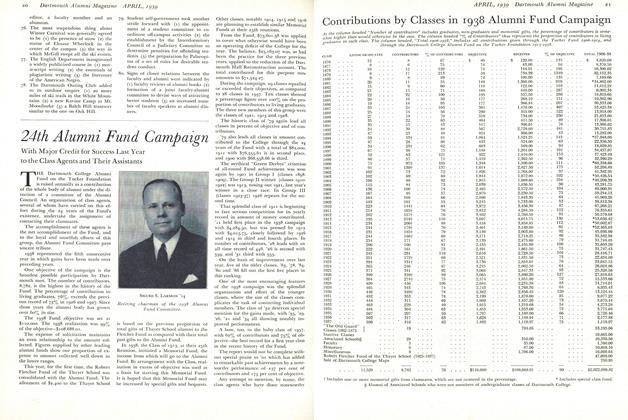

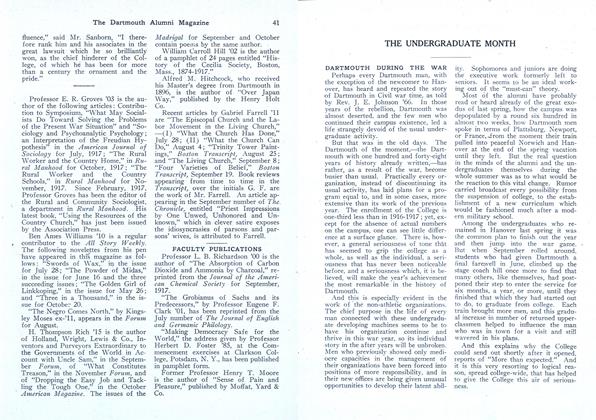

Cover Story24th Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1939 By Luther S. Oakes '99, Edward K. Robinson '04, Fletcher R. Andrews '16, 2 more ...

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November 1917 -

Books

BooksThe Graphic Arts in Belgium

November 1938 -

Books

BooksJOURNALISM AND THE STUDENT PUBLICATION

June 1952 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksEDUCATION AND LIFE

January, 1931 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksLooking Back

April 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksSPUN SEQUENCE.

July 1962 By RICHARD EBERHART '26