NEW HISTORY PUBLISHED THIS MONTH

DEAN OF FRESHMEN

THE COLLEGE ON THE HILL: ADARTMOUTH CHRONICLE. Editedby Ralph N. Hill '39. Hanover: Dartmouth Publications, 1965. 380 pp., illustrated. $10,00.

IT will take iron self-discipline on the part of this writer if the review of this beautiful book avoids being tagged as a rave notice. The College on the Hill is superbly planned, subtly organized, gracefully and concisely written, and edited with extraordinary selectivity. Handsomely designed, illustrated and printed, it is a magnificent piece of book-making.

This Dartmouth Chronicle fills a long-felt need; but the reader, in finishing its 300 pages, will find that it has done much more than that. It develops a sense of movement, and of power and continuity of institutional purpose, that marks it significantly as the first of the Bicentennial publications.

"An educational enterprise at its best is always in the process of becoming rather than a finished thing ready for its official portrait," writes President Dickey in the Foreword. This sense of continuous becoming is conveyed throughout the pages of this book.

Some readers may wonder what one means in saying this chronicle fills a long-felt need. Dartmouth has been singularly fortunate in her historians, and the serious scholar will find a well-nigh overwhelming richness of resources. The problem is the embarrassment of riches. Richardson admirably consolidated available resources in his definitive history published in 1932, combining sound historical scholarship with charming writing; but while almost everybody "means to" read Richardson "from cover to cover," how many have actually read his 800 highly readable pages in any reasonably consecutive fashion? Quint's The Storyof Dartmouth served the purposes of a popular Dartmouth history from its publication in 1914 until it went out of print about 1930. Ever since, persons holding responsibility for Dartmouth publications have fretted about the need to fill this gap. More recently, another historical need has been growing. Richardon's history can be considered definitive only up to the beginning of the Hopkins administration in 1916. That is now a half-century ago.

The College on the Hill does not pretend to be the definitive history of the Hopkins and Dickey administrations and at this point in time, could not be; but with careful perspective and meticulous accuracy, it provides a substantial historical account of the last fifty years and brings the Dartmouth chronicle neatly up to the eve of the third century as a Bicentennial backdrop.

President Dickey's foreword is a powerful kick-off for this book. "The difficulty," he says, "is that the College seen in its entirety is always more varied and more ongoing than it ever seems when put to words." This makes the reader, as he goes through the pages, more appreciative the Chronicle does convey. Mr. Dickey sets the book in motion by translating Dartmouth's historic purpose into her continuous becomingness. Even for those who have aversions for other people's puns, the title, "Dartmouth on Purpose," will prove meaningful and apt. The writing here is at his very best - concise but not, as sometimes, almost too tight. One predicts that many readers by instinct will turn back to this foreword after the final chapter, as this reader did, to find that it is as suitable and effective a conclusion as it is a beginning of a chronicle that will be forever unfinished.

One of the most remarkable qualities of this book is the way it coheres. It has five authors. It presents the Dartmouth story in five parallel chronological narratives about the College, the Place, the Faculty, the Students, and the "Wearers of the Green." Yet it happily escapes all the manifest dangers of such a format. Its five narratives are skillfully interwoven into one chronicle. It is one book - not a compilation or anthology. Its several authors write in styles which are distinctive, yet they come together in harmony. And the miracle for which Ralph Hill earns his summa cum laude as editor is the absence of repetition.

It is no surprise to find Author Hill fully as skilled a craftsman as Editor Hill. The succinct 67 pages of his opening chapter, "The Historic College," would stand by itself as a gap-filling short history of the College except that it ends a bit too soon, in 1893. He encompasses so much in so little space not by using broad strokes but by being skillfully selective and characteristically concise, leaving himself room for some vivid detail and giving the reader intermittent tastes of the Hill brand of sly humor. Readers who think they have "read it all before" will find a freshness in the narrations of familiar events that makes them seem somehow new.

In the earliest pages of Stearns Morse's "Chapter II: The Place" the subtle organization of this book becomes apparent. Professor Morse sticks faithfully to his topic; i.e., Dartmouth's environment from "then" to now. He covers the town and countryside from the hewing of the first pines to the Super Duper market, from the stagecoach to this afternoon's four o'clock jam at the Main and Wheelock traffic light, and the town characters from Hod Frary, Ira Allen and Jason Dudley to the Tanzis and Julius Mason's fall into the cistern. But many of the town characters were also College characters and could have fitted quite appropriately into Chapter I or Chapter III: "Bobby" Fletcher, Nathan Smith and Dr. Gile, for example. They fit best here, however, and hence have been sedulously edited out of other contexts. This is a charmingly written, wholly delightful chapter.

In "Chapter III: The Faculty," Professor Morse begins again at the beginning of the two-century chronology and starts with Eleazar Wheelock and his four tutors. He proceeds, again with scrupulous avoidance of repetition, through a gallery of well-remembered teachers vividly portrayed. He intermittently takes note of the changing conditions and curricula under which they taught. He frankly confesses that his choices have been "governed by my personal bias of interest, recollection or affection." At the same time he says he has "not intended to include in this account anyone who was dull or mediocre." Indeed he has not.

Author Hill - always, no doubt, operating under the minatory scrutiny of Editor Hill, but always surely having fun at his task - returns with "Chapter IV: The Students." This is one of the most colorful chapters, starting vividly with the trek to Hanover of Joseph Vaill and the Osborn boys, and the rigors of their college days; and proceeding rapidly and sometimes gaily through the ordeals, pranks, and peccadilloes of successive generations of Dartmouth men, their changing numbers, origins, character, mores, purposes, goals, and destinations. There is much that seems fresh and new here, and much that is amusing. Clearly Ralph Hill had his greatest fun in this chapter.

F. William Andres '29, a Trustee of the College and erstwhile member and chairman of the Dartmouth College Athletic Council, collaborates with Ernest Roberts, DCAC publicity director, on "Chapter V: The Wearers of the Green." After dispatching Ledyard down the Connecticut on his canoe trip and noting the track and field feats of Dr. Wheelock's Indians, they cover Dartmouth sports from football to football: from the early Dartmouth football in which classes competed en masse against one another, to the recent international triumphs of Dartmouth "ruggers." There's a good deal of the other kind of football in between, along with many other sports.

When "Chapter I: The Historic College" ended at 1893, a reader may have wondered why it stopped there, 72 years ago. But it is quickly clear as one starts "Chapter VI: The Modern College" why this concluding section starts here with President Tucker, because this is where the modern College begins. To have hitched Dr. Tucker back there as an appendage to President Bartlett would have been like hitching the locomotive onto the caboose. Here Ralph Hill updates Dartmouth's history with his customary competence, and breaks new ground with his accounts of the Hopkins and Dickey administrations.

No chronicle was ever more amply, imaginatively and discriminatingly illustrated. Numbering about 100, the illustrations embrace the widest variety of medium and subject matter - portraits, photographs, engravings, line drawings, cartoons, printed programs - of all sizes and shapes, each set just right on its page and closely related to the text.

Scattered through the book are three-or four-line inserts of quotations printed in a quietly distinctive brick-red. For this delightful and original feature, the editor earns still another encomium. These carefully selected nuggets mined from the writings of Wheelock, Tucker, Hopkins, Dickey, and numerous others, ranging from Dwight D. Eisenhower to Alonzo A. Stagg, were not discovered and selected in any small number of hours.

A reviewer must find something to cavil at to prove he's approached his task conscientiously. Pedants immersed in aptitude scores and percentiles may raise eyebrows at the reference to aptitudes "in the seven hundred percentile range" (page 258). If there were thousands of V-5 aviation cadets around here during World War II, they escaped this observer's eye. This reader relished every paragraph of "The Faculty" chapter, but younger readers who have not known all the latter-day characters mentioned and shared Stearns Morse's affection for them may find this section over-long in proportion to the disciplined dimensions of the other chapters. The omission of captions for the illustrations is esthetically pleasing, leaving the handsome pages typo- graphically uncluttered. At first the reader enjoys an identification game, checking his guesses against the "answers" in the front. Eventually, however, this reader concluded that he, for one, would sacrifice this particular esthetic value to the peruser's convenience. Surely this is an insubstantial catalog of cavillings for a truly conscientious caviller.

From end-paper to end-paper (fine drawings of the "Prospect of College and Village" in 1864 and 1964, respectively), The College on the Hill reflects in every detail the four years that went into its preparation. From cover to cover, its superb design and production bear the unmistakable mark of that rare artificer of book-making, Ray Nash, who regrettably omitted a colophon. This beautiful book deserves one. Good indexes cannot just be taken for granted. This one was done by Richard Morin.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

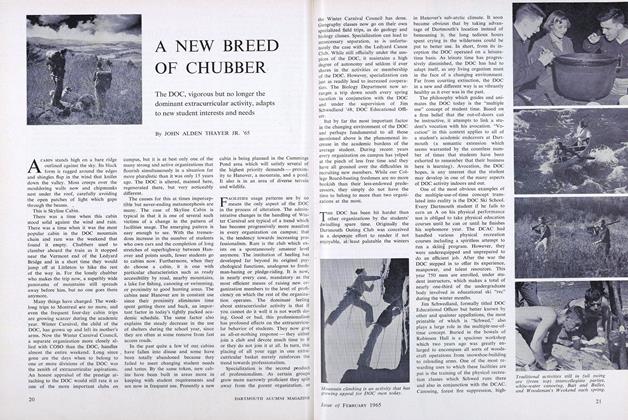

FeatureA NEW BREED OF CHUBBER

February 1965 By JOHN ALDEN THAYER JR. '65 -

Feature

Feature"It Was Quiet, Serene, and Beautiful"

February 1965 By GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37 -

Feature

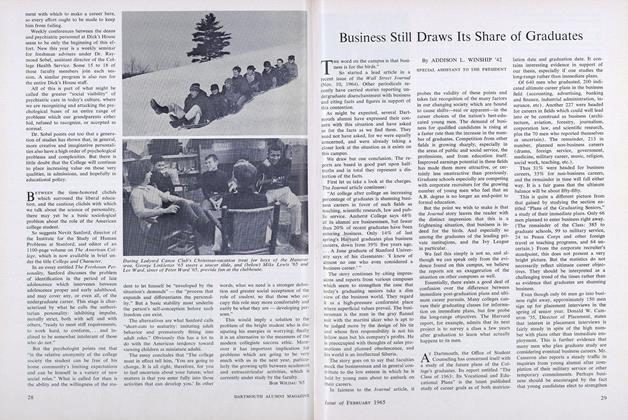

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

February 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

February 1965 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleThe Battle of the Non-Teachers

February 1965 By M. DANIEL SMITH '46

ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30

-

Article

ArticleHanover Holiday Plus Alumni College

May 1937 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksAN ACCOUNT OF CALLIGRAPHY PRINTING IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

March 1940 By Albert I. Dickerson '30 -

Article

ArticleA DAY WITH A TRAINEE

January 1944 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksAn Authoritative Obituary for "Well-Roundedness"

June 1962 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Article

ArticleValedictories to Retiring Class Agents

April 1942 By Harvey P. Hood II '18, Albert I. Dickerson '30 -

Cover Story

Cover Story24th Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1939 By Luther S. Oakes '99, Edward K. Robinson '04, Fletcher R. Andrews '16, 2 more ...