TV Is Credited with a Major RoleIn Expanding the Educational View

PRESIDENT, EDUCATIONAL BROADCASTING CORPORATION

FIFTY YEARS AGO the American college or university proudly reflected the alleged characteristics of our present-day British "Establishment." It was intended for the few, comparatively speaking, and it kept its activities and its secrets to itself. In fact, it went still further, for once its own initiates had achieved their various degrees, even they were rather summarily ignored except for re- unions, traditional gatherings at sports events, and requests for financial assistance.

But a radical change has come about in recent decades. The medieval slits in the ivory tower are being transformed into broad and open expanses of modern picture windows. These invite the curious to look in and they make such peeping easy, not only for the college or university alumnus but for everybody who is interested. They also invite the scholar to look out and see clearly his responsibility for developing the larger community culture. With so much more viewing and so much less wall, the whole tower is beginning to weaken and will soon disappear. No greater blessing can be vouchsafed to a democratic nation. And no other single technological tool presently in existence can do more to bring about this blessing than can television when it is properly used.

The history of this rather amazing phenomenon, one that within a space of twenty years has become the tyrant of public time and taste, is worth examining.

It was almost inevitable in America that television, the brainchild of scientific and technical workers, should have had its major force devoted to promoting values stemming from technology and materialism. Television was merely following a pattern that radio had previously established, In the 1920's the Federal Communications Commission assigned a large number of AM radio frequencies to educational purposes. One by one, however, either they were not taken up at all or when they were, they soon withered away from lack of financial support and stability. Gradually these frequencies gravitated to commercial interests quick to see the profit possibility, and a great opportunity to give education its place in the sun was lost.

When television came into being, education once more was neither willing nor ready to take on the expense and responsibility of operating VHF channels. With almost no exceptions such channels were taken over by commercial interests, just as had occurred in radio. A huge and powerful industry emerged, dominating virtually all the available channels and pointing its energies toward reaching and holding a great mass audience of all age levels and of all social, economic, and educational conditions.

That the first television activity of consequence in this country was geared to commercialism is significant. Its artistic and educational possibilities were sublimated from the beginning to those essential for advertising and sales. Programs of quality and variety do develop from a policy of commercialism, it is true, but all too many programs of inferior quality or questionable purpose also develop because of this policy.

Today's concentration upon the advertising of products and the development of programs sure to please and rarely intended to tax the mind has led to an emphasis upon values in life that are compatible with a technological and materialistic society. The possession of things in larger quantity and better quality than ever before, already a dominant part of American life before the existence of television, has become even more important. Humane and individualistic values have been dealt with cavalierly. Adventure has been so completely equated with violence and bloodshed that a callousness toward the dignity of individual human life has unwittingly been fostered, with a minimum of countervailing portrayals of gentleness and graciousness. Conformity of many sorts has been encouraged—in dress, habits of eating, drinking, smoking, and the like; in recreational pleasures; in transportation; and even in family relationships. Correspondingly, a strong sense of the importance of security and an almost pathological avoidance of controversy have made their mark upon the values of the viewer.

Just as this medium affects consumer habits and values, so does it also affect and alter standards of taste. If ratings are to be believed, the mass taste of our citizenry tends very largely toward western drama, family situation comedy, detective fiction, popular ballad singers, and comedians. It reflects a willingness to view the same stock plots and stereotype characters week after week together with an equal willingness to forego any subtleties of dramatization or characterization. It reflects wholesale acceptance of the slick, the smooth, the competent program in preference to the provocative. It reflects a kind of hypnosis or suspension of critical judgment overcoming the viewer as he sits hour after hour before his set.

Another unmistakable influence of television relates to the disappearing regional differences in our population. Through network broadcasting and syndicated programs the same drama, music, comedy, special events, and even commercial messages are seen from border to border. Urban and rural citizens are subject to the same stimuli The same catchwords are parroted everywhere from the television screen, and the same star performers are idolized. All this testifies to the power and importance of the word "mass" inherent in the term "mass communications."

IT should be noted that as these phenomena of mass taste have developed, a minority of respectable size has also emerged, a minority searching for the occasional program of high purpose and merit with which the total television schedule is dotted. Educational television seeks to provide a broader set of cultural choices for this minority and also undertakes to explore more systematically the instructional possibilities of the medium.

At present there are over eighty educational television stations, with more to come. They vary greatly in size, power, financial stability, and program emphasis. There are also a number of closed circuit operations in school systems and universities. Together these illustrate the three purposes of educational television: to offer instruction through open circuit transmission, thus making the broadcasts available in school or at home; to offer instruction through closed circuit transmission, thus limiting the broadcasts to a single building or group of buildings; to offer to the community cultural programs encompassing discussion of literature, art, or public affairs and performances of music, dance, drama, and so on.

The most important possibility of educational television stems from the tradition of education itself, when properly interpreted. This tradition holds the individual in great respect, recognizing his potentiality for growth and endeavoring to help him toward fulfillment of that potentiality. A sound process of education tries constantly to raise the level of understanding, to encourage students to higher expectations of their individual possibilities, and to protect them from being frozen into a conformist mass. If educational television is to perform its mission well, it must operate according to this self-same tradition, for if it questions the intellectual capacity of its viewers, it ceases to be creative and merely perpetuates mediocrity.

So much for the history and characteristics of the medium. Of what importance is all this to alumni?

The potentialities of television should be of interest to college and university alumni for at least three significant reasons. First, from a purely personal and selfish point of view, alumni should recognize the greatly expanded "refresher" possibilities television can make available. Some institutions of higher education, sensing the need for a deeper sort of relationship between themselves and alumni, are attempting systematically to revive the intellectual interests of their graduates. A goodly number present such a revival opportunity, for example, through the so-called "alumni college," usually organized for a few days at commencement time; a few institutions provide similar opportunities at periodic intervals of the academic year; a very few maintain an ongoing process of alumni education that parallels the regular program at least partially. The newly created Alumni Center at M.I.T. is an outstanding example of this kind of effort.

But it is frequently difficult for one to return to school for a sustained period of time or even for an occasional evening or weekend in order to be updated in one's professional specialty or even in more general areas. And it is even more difficult today for the institution to find rooms and other resources to mount such a program, being so absorbed in the almost overwhelming problem of how to provide education adequately for the increasing number of undergraduate students.

A logical solution would be the offering of telecourses for alumni, the subject matter fields chosen according to the wishes of alumni themselves, the courses presented by the college faculty and made available not only to alumni but to all who have the urge to participate. A systematic, academically worthwhile program could be developed without the red tape and clutter of rules about course credit hours and all the rest. It could be adult or continuing education based upon its finest motivation, namely that of learning for the joy of learning and nothing more. It could encompass literature, the arts, the sciences, and world affairs. And it would require no classrooms, no subway or bus or automobile rides, no large number of faculty, no registration procedures, no examinations.

Second, from such a beginning in adult education by television, spurred by the interest of alumni, could come more confidence on the part of our institutions of higher education in the adaptation of this approach for the undergraduate student also - a more complicated procedure for the latter, perhaps, but nonetheless possible. Results of experiments show conclusively that there are many ways to use television effectively, ways that make possible new techniques of instruction or that help in coping with enormous student bodies and inadequate physical facilities. This is not to advocate the substitution of television for all our conventional methods; it is rather to plead for its intelligent and proper use where it performs a particular service otherwise not practicable. For example, it can bring each student in a class of three hundred as close to the slide under the biology professor's microscope as though he were at the professor's side. Similarly, it can guarantee that the maximum number of students will have the opportunity to benefit from the instruction of the most distinguished and ablest faculty members.

Third, the potentialities of television should make alumni realize more fully their responsibilities as educated men and women for the cultural development of their communities. This powerful instrument can open new vistas to great numbers of people hitherto unreached. Mass education and mass culture can be raised to new levels of understanding and appreciation once there is an awareness of how important and how attainable such levels are. Democratic approaches to culture are not predestined to culminate in mediocrity. Only because there has been a passive attitude or even a snobbish attitude on the part of intellectual leaders has such mediocrity come into being. But with intelligence and perseverance on the part of the community leaders and with the use of all the communicative means at hand, new emphasis can be placed upon the fundamental values by which we live and the gracious attributes of an enlightened society.

College and university alumni must be in the forefront of such a community movement since they are fitted by background for the task. And in performing this task they can and should turn to the exciting and rewarding possibilities of reaching into every home by television. The process of elevating the public taste may be slow but, if properly and assiduously pursued, it will be sure. Television can carry on this process inexpensively and effectively, offering a rich and varied sampling of all aspects of education and culture and strengthening the inner fiber of America.

Here, then, is a new mission for alumni - contemporary, vital, unceasing, and dynamic.

Copyright 1963 by Editorial Projects for Education, Inc.Sketch by Mary Sandoe

About the Author: DR. SAMUEL B. GOULD, President of Educational Broadcasting Corporation, operators of Channel 13 (WNDT) in New York, has had a long and distinguished career in education and communications. Prior to assuming his new position, Dr. Gould was Chancellor of the University of California at Santa Barbara for three years. From 1954 to 1959 he was President of Antioch College. Dr. Gould was educated at Bates College and at New York, Oxford, Cambridge, and Harvard Uni- versities. After secondary school teaching, he organ- ized and directed the Department of Communications at Boston University. Dr. Gould is a trustee of Wilberforce University, the Thomas Alva Edison Foundation, and the Charles F. Kettering Founda- tion. He is also chairman of the board of the Broadcasting Foundation of America.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHORNING: Invention of the Devil

December 1963 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

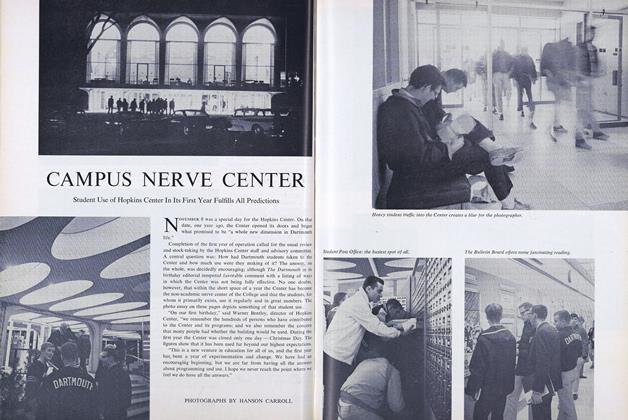

FeatureCAMPUS NERVE CENTER

December 1963 -

Article

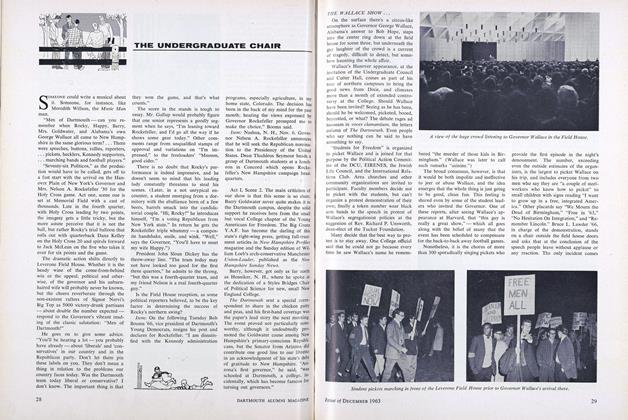

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1963 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1963 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON -

Class Notes

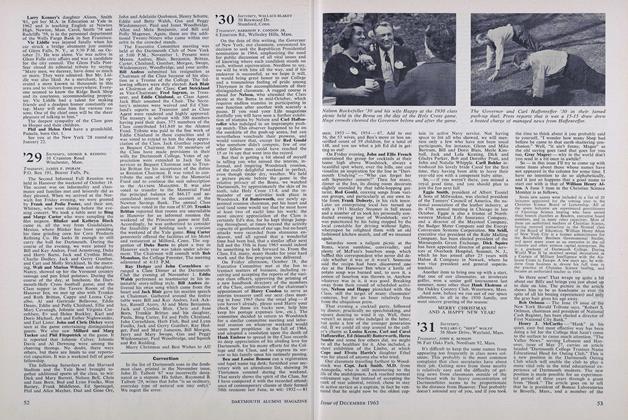

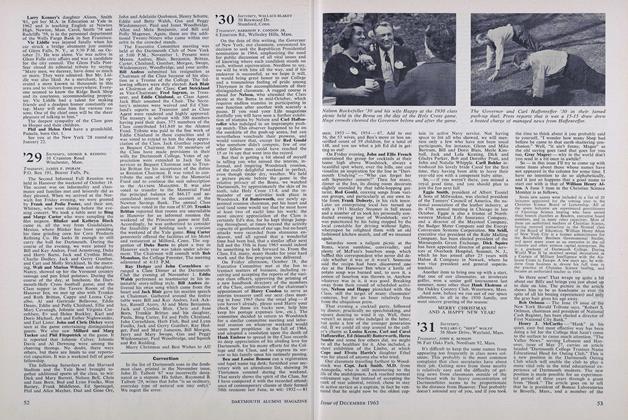

Class Notes1930

December 1963 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HARRISON F. CONDON JR -

Class Notes

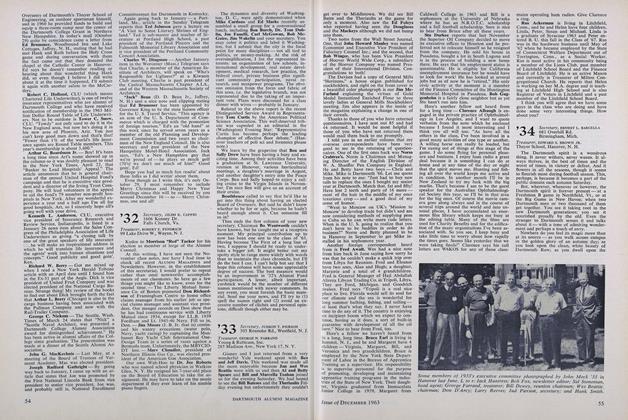

Class Notes1933

December 1963 By JUDSON T. PIERSON, GEORGE N. FARRAND

Features

-

Feature

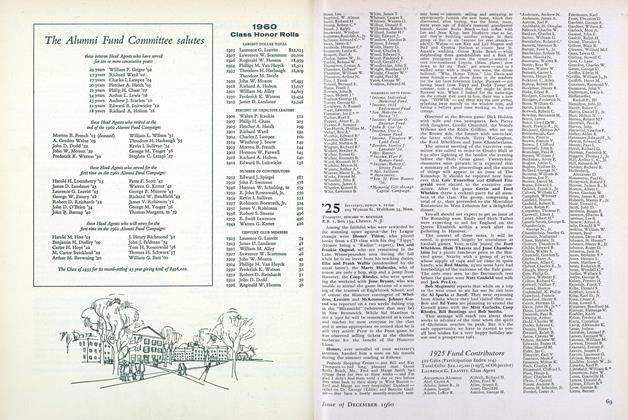

Feature1960 Class Honor Rolls

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1961 -

Feature

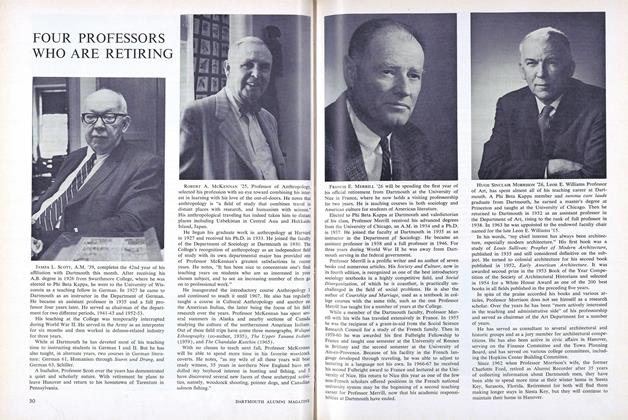

FeatureFOUR PROFESSORS WHO ARE RETIRING

JUNE 1969 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Plan

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureFrost, Mencken, And Webster's Socks

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 By Howard Coffin -

Feature

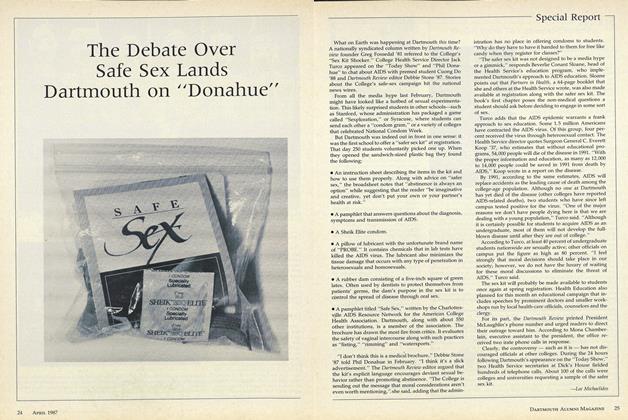

FeatureThe Debate Over Safe Sex Lands Dartmouth on "Donahue"

APRIL • 1987 By Lee Michaelides