SOMEONE could write a musical about it. Someone, for instance, like Meredith Willson, the Music Man man.

"Men of Dartmouth - can you remember when Rocky, Happy, Barry, Mrs. Goldwater, and Alabama's own George Wallace all came to New Hampshire in the same glorious term?...There were speeches, buttons, rallies, reporters, ...pickets, hecklers, Kennedy supporters, ...marching bands and football players."

"Seventy-six Politicos," as the production would have to be called, gets off to a fast start with the arrival on the Hanover Plain of New York's Governor and Mrs. Nelson A. Rockefeller '30 for the Holy Cross game. Act one, scene one is set at Memorial Field with a cast of thousands. Late in the fourth quarter, with Holy Cross leading by two points, the imagery gets a little tricky, but the more astute perceive that it is not the ball, but rather Rocky's trial balloon that rolls out with quarterback Dana Kelley on the Holy Cross 20 and spirals forward to Jack McLean on the five who takes it over for six points and the game.

The dramatic action shifts directly to Leverone Field House. Whether it is the heady wine of the come-from-behind win or the appeal, political and otherwise, of the governor and his auburnhaired wife will probably never be known, but the cheers reverberate through the non-existent rafters of Signor Nervi's Big Top as 5000 victory-drunk partisans - about double the number expected - respond to the Governor's vibrant reading of the classic salutation: "Men of Dartmouth!"

He goes on to give some advice. "You'll be hearing a lot - you probably have already - about 'liberals' and 'conservatives' in our country and in the Republican party. Don't let them pin these labels on you. They don't mean a thing in relation to the problems our country faces today. Was the Dartmouth team today liberal or conservative? I don't know. The important thing is that they won the game, and that's what counts."

The score in the stands is tough to assay. Mr. Gallup would probably figure that one senior represents a goodly segment when he says, "I'm leaning toward Rockefeller, and I'd go all the way if he shows some gear today." Other comments range from unqualified stamps of approval and variations on "I'm impressed," to the freeloaders' "Mmmm, good cider."

There is no doubt that Rocky's performance is indeed impressive, and he doesn't seem to mind that his leading lady constantly threatens to steal his scenes. (Later, in a not untypical encounter, a student emerging from a dormitory with the ebullience born of a few beers, barrels smack into the candidatorial couple. "Hi, Rocky!" he introduces himself, "I'm a voting Republican from New York state." In return he gets the Rockefeller triple whammy - a composite handshake, smile, and wink. "Well," says the Governor, "You'll have to meet my wife Happy.")

President John Sloan Dickey has the throw-away line. "The team today may not have looked too good for the first three quarters," he admits to the throng, "but this was a fourth-quarter team, and my friend Nelson is a real fourth-quarter guy."

Is the Field House reception, as some political reporters believed, to be the key factor in determining the success of Rocky's northern swing?

Item: On the following Tuesday Bob Booms '66, vice president of Dartmouth's Young Democrats, resigns his post and declares for Rockefeller. "I am dissatisfied with the Kennedy administration programs, especially agriculture, in my home state, Colorado. The decision has been in the back of my mind for the past month; hearing the views expressed by Governor Rockefeller prompted me to make the choice," Booms said.

Item: Nashua, N.H., Nov. 6. Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller announces that he will seek the Republican nomination to the Presidency of the United States. Dean Thaddeus Seymour heads a group of Dartmouth students at a luncheon in Concord which opens Rockefeller's New Hampshire campaign headquarters.

Act I, Scene 2. The main criticism of our show is that this scene is so short. Barry Goldwater never quite makes it to the Dartmouth campus, despite the solid support he receives here from the small but vocal College chapter of the Young Americans for Freedom. The Big Green Y.A.F. has become the darling of this state's right-wing press, getting full-treatment articles in New Hampshire Profiles magazine and the Sunday edition of William Loeb's arch-conservative Manchester Union-Leader, published as the NewHampshire Sunday News.

Barry, however, got only as far north as Henniker, N.H., where he spoke at the dedication of a Styles Bridges Chair of Political Science for new, small New England College.

The Dartmouth sent a special correspondent to share in the chicken patty and peas, and his first-hand coverage was the paper's lead story the next morning. The event proved not particularly note-worthy, although it undoubtedly promoted the Goldwater cause among New Hampshire's primary-conscious Republicans, but the Senator from Arizona did contribute one good line to our libretto in an acknowledgment of his state's debt of gratitude to New Hampshire. "Arizona's first governor," he said, "was schooled at Dartmouth, a college, incidentally, which has become famous for turning out governors."

THE WALLACE SHOW...

On the surface there's a circus-like atmosphere as Governor George Wallace, Alabama's answer to Bob Hope, steps into the center ring down at the field house for scene three, but underneath the gay laughter of the crowd is a current of tragedy, difficult to detect, but some-how haunting the whole affair.

Wallace's Hanover appearance, at the invitation of the Undergraduate Council and Cutter Hall, comes as part of his tour of northern campuses to bring the good news from Dixie, and climaxes more than a month of extended controversy at the College. Should Wallace have been invited? Seeing as he has been, should he be welcomed, picketed, booed, boycotted, or what? The debate rages ad nauseam in voces clamantium, the letters column of The Dartmouth. Even people who say nothing can be said to have something to say.

"Students for Freedom" is organized to picket Wallace and is joined for that purpose by the Political Action Committee of the DCU, EIRENES, the Jewish Life Council, and the International Relations Club. Area churches and other community organizations are invited to participate. Faculty members decide not to picket with the students, but can't organize a protest demonstration of their own; finally a token number wear black arm bands to the speech in protest of Wallace's segregationist policies at the suggestion of Rev. Richard P. Unsworth, dean-elect of the Tucker Foundation.

Many decide that the best way to protest is to stay away. One College official said that he could not go because every time he saw Wallace's name he remembered "the murder of those kids in Birmingham." (Wallace was later to call such remarks "asinine.")

The broad consensus, however, is that it would be both impolite and ineffective to jeer or abuse Wallace, and the idea emerges that the whole thing is just going to be good, clean fun. This feeling is shared even by some of the student leaders who invited the Governor. One of these reports, after seeing Wallace's appearance at Harvard, that "this guy is really a great show," — which all goes along with the belief of many that the event has been scheduled to compensate for the back-to-back away football games.

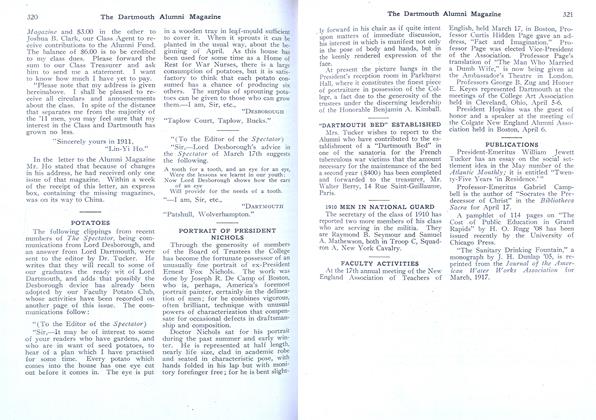

Nonetheless, it is the chorus of more than 300 sporadically singing pickets who provide the first episode in the night's denouement. The number, exceeding even the outside estimates of the organizers, is the largest to picket Wallace on his trip, and includes everyone from two men who say they are "a couple of steel-workers who know how to picket" to small children with signs reading "I want to grow up in a free, integrated America." Other placards say "We Mourn the Dead of Birmingham," "Free in '63," "No Hesitation On Integration," and "Remember Lincoln." Bruce L. Lawder '66, in charge of the demonstration, stands on a chair outside the field house doors and asks that at the conclusion of the speech people leave without applause or any reaction. The only incident comes when a student goes up to Lawder and calls him a "nigger-loving b-d."

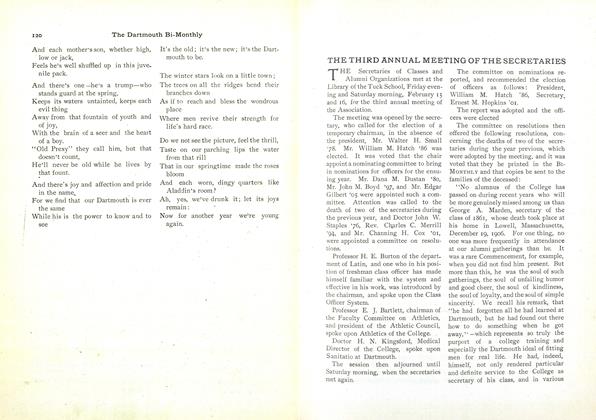

The overflow crowd of 3600 is seated quietly and efficiently by Green Key members and applauds when Wallace is introduced. The polished and personable - but still folksy - demagogue is in his best out-on-the-hustings style as he begins with a tribute to New Hampshire's long states' rights tradition. Loud applause is given by the partially non-Dartmouth crowd when he says, "We in Alabama don't believe that everything coming down from Washington is 'heaven-sent'." He has a good story about the old Alabama storekeeper who was willing to change the Washington counterfeiter's $18 bill, offering the counterfeiter his choice of "two nines or three sixes." Applause also follows his remark that "anyone would be an improvement over the present administration in Washington," but his best line is one he used at sexscandalized Harvard the night before: "I hope you all don't believe everything you read about Alabama because I sure don't believe everything I read about Harvard."

For the most part, however, the crowd is amused rather than impressed, prefer ring to laugh at rather than hiss unpopular statements, such as Wallace's contention that the southern whites have helped the Negro, "brought him to the point where he is today." This prompts him to quip, "I don't understand. You laugh when I don't think you will, and don't laugh when I think you should." The only serious booing is reserved for the remark that "segregation is the law of nature from South Africa to New York."

The Alabama Governor is least effective when reading his prepared speech on the 1954 school segregation case, a speech which The Dartmouth classifies as "legal drivel" in its editorial the following morning. But, that same editorial wonders what the effect of that same speech would be on a southern audience which wanted to believe in segregation. From this standpoint the Governor is indeed a "frighteningly fascinating figure."

A somewhat favorable impression of Dartmouth students is voiced by Wallace, who praises, believe it or not, their neat appearance — as compared with Harvard's. The students aren't quite sure what they think of him. Some are surprised that he is not a "real hick," others concede that he has "a few good points." Others are quite upset by the audience reaction. Lawder, for instance, later tells this reporter that "the real tragedy is that most people don't understand how serious the situation is." Objections are also heard to the misuse of statistics by Wallace in regard to the number of Alabama's Negro school teachers (he didn't say they were teaching in all-Negro schools), and the number of Negroes voting in Alabama (the Governor apparently inflated the figure).

The majority, though, regard the speech and question period purely as entertainment, and the dissatisfaction with the maturity of the Hanover audience felt by many is well summed up by Professor of Psychology Milton J. Rosenberg in a letter to The Dartmouth: "Certainly some quality of compassion is missing, some quality of responsible involvement in vital and tragic social issues is absent, when hundreds of students can approach such a performance in an unreflective or carnival mood."

The show isn't really over. Rocky, Barry, and maybe even George will be back in March for the New Hampshire primary and Act Two. Don't miss it.

ALL GOOD THINGS...

It was sad, yes it was sad, on that sickly warm afternoon in Allston, Massachusetts, when a Harvard football team brought to an inglorious end the longest major college undefeated string in the nation. It was a most unhappy group that filed out of the Dartmouth side of the stadium to seek refuge and forgetfulness in the bars and hotel rooms of Boston. Yet there was no escape. One man came into a small grocery store down near South Station late that evening in quest of some ginger ale. "You must be from Dartmouth," said the small, whiteaproned man behind the counter in a not unsympathetic way. How did he know? "Because you look so sad."

THE AX-MAN COMETH...

Each fall the cliches of rush are dragged out like Christmas tree ornaments, to be used briefly then put away for another year as soon as the occasion is over.

The "rushees" are soon classified. There is the sad case of the "screamers" who are "flushed" by the "ax-men." The "glad-handers" and "face-men" probably will not get a "visitation" the next afternoon. But the "sincere guys" with "a lot to them," often athletes, or "jocks," ... these are put on the "S.O.S. list" to be "sunk on sight." After "sinking" they continue on to become brothers and ex officio "good men."

Under these conditions one man accomplished what can he considered nothing less than a linguistic breakthrough. Requested to pin down his negative reaction to a certain rushee he thought for a moment. "I'd have to say," he began, "that he is, well...squamulous."

The word, for what it's worth, means "minutely scaly."

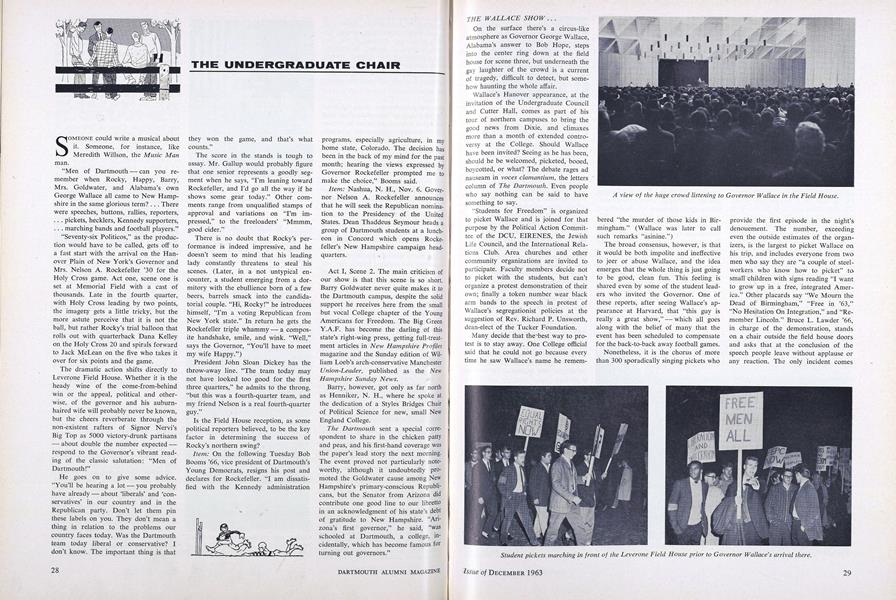

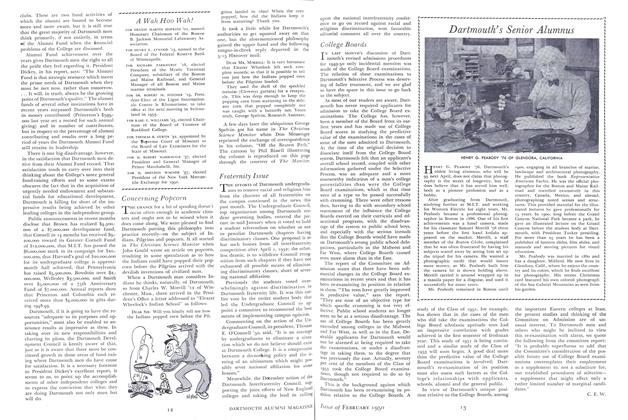

A view of the huge crowd listening to Governor Wallace in the Field House.

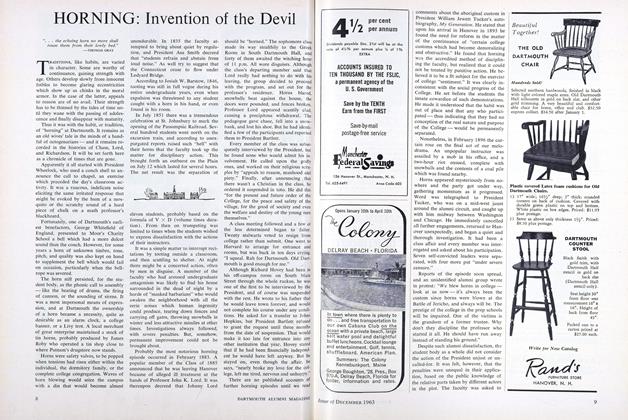

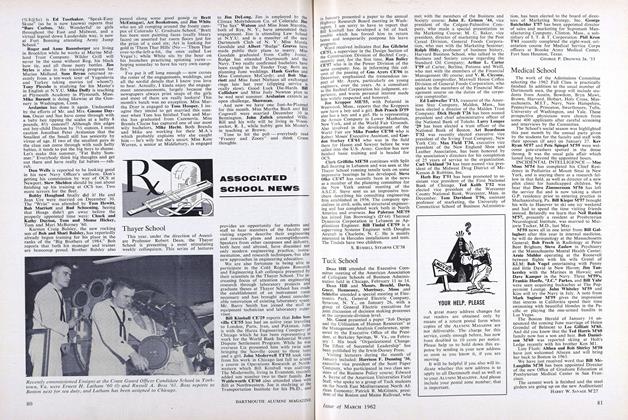

Student pickets marching in front of the Leverone Field House prior to Governor Wallace's arrival there.

Student pickets marching in front of the Leverone Field House prior to Governor Wallace's arrival there.

For the first time since 1956 the freshmen last month lost the tug of war to the sophomores. In a riotous aftermath, the '67s claimed the sophs had upperclass ringers andtied their end of the rope to a tree, but the 2-1 score was declared official and freshmen had to keep on wearing their beanies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Disappearing Ivory Tower

December 1963 By SAMUEL B. GOULD -

Feature

FeatureHORNING: Invention of the Devil

December 1963 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureCAMPUS NERVE CENTER

December 1963 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1963 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1963 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HARRISON F. CONDON JR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

December 1963 By JUDSON T. PIERSON, GEORGE N. FARRAND

DAVE BOLDT '63

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleDanube Adventure

FEBRUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE THIRD ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES

FEBRUARY, 1907 -

Article

Article"DARTMOUTH BED" ESTABLISHED

May 1917 -

Article

ArticleGIFT FROM HARVARD MEN TO DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

August, 1926 -

Article

ArticleNo Cloak, No Dagger

November 1948 -

Article

ArticleCollege Boards

February 1950 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleTuck School

March 1962 By GEORGE P. DROWNE Jr. '33