By Michael H. Cardozo'32. Ithaca: Cornell University Press,1962. 142 pp. $3.50.

Professor Cardozo has written a book that should be read by all serious observers of the international scene and by all who are concerned about making the influence of the United States more effectively exerted. He defines his terms carefully, making it clear that he refers to diplomats and diplomacy in the older sense of being related to the practice of negotiation. He states his purpose equally clearly, as being "to consider what kinds of diplomats and diplomatic practices the United States will have to develop for the successful conduct of relations with other peoples and nations in an atmosphere of international cooperation and through various kinds of international organizations."

Much of the book is an explanation of how the need for new types of diplomat have developed in the last twenty years and how their work is actually carried on. All this is useful indeed and in itself would make the book justified. From this basis Mr. Cardozo points out that we are not using the best-trained people in the best ways and makes suggestions for improvement. Much of what he says is unfortunately true, but it may be suggested, with some hesitation, that the picture is not quite so bad as painted and that changes are taking place rather rapidly.

There may be, for example, a significant share of the total job still for the older type of diplomat. Indeed, international organizations are in many ways only switchboards for bi-lateral negotiation. Last October, within two weeks spent at the United Nations, Secretary Rusk talked, that is negotiated, separately with the diplomats of more than sixty nations.

There may be, also, less of the "deplorable tendency of the career diplomats to treat their new colleagues as stepchildren of the foreign service." Ten years ago as a novice bureaucrat I was not sure whether the real enemy of the State Department was the Soviet Union or the U. S. Economic Cooperative Administration. Today even the Information Service is well thought of, and an officer of USIS has been made an ambassador. Officers from all services are freely inerchanged, on loan to other agencies. More significant, perhaps, is a fact I discovered from reading this fall several hundred personnel files of Foreign Service Officers - that the older, generalist career officer is to a real degree disappearing. Within the ranks of the Foreign Service itself there are developing a great many who want to deal with nothing except one special area - economics, science, labor, public relations, etc. Of the three career Foreign Service Officers serving with me on the Selection Board panel, two were such specialists as Mr. Cardozo wants, without the faintest knowledge of how to grant a visa.

All this is, however, avoiding the major issue — should there be one or several foreign services? There should be only one, with room within it for every type of officer, generalist or specialist, and all trained to meet the needs of the modern world. Mr. Cardozo quite correctly is impatient for the change to be complete.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

February 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

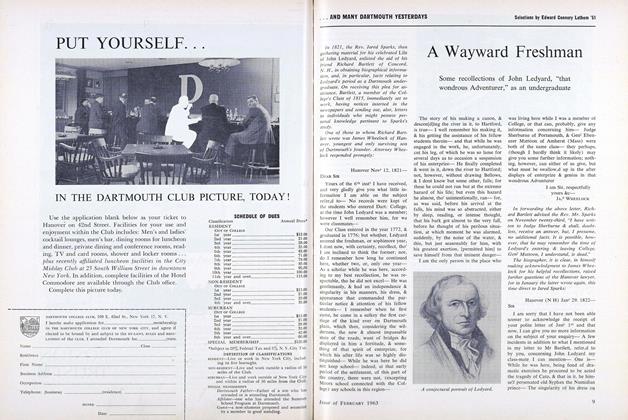

FeatureAND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

February 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

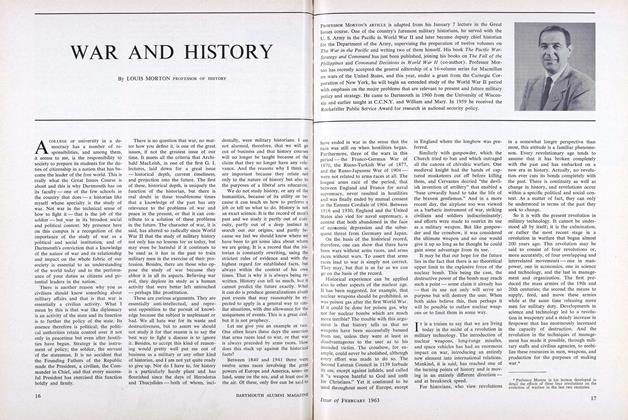

FeatureWAR AND HISTORY

February 1963 By LOUIS MORTON -

Feature

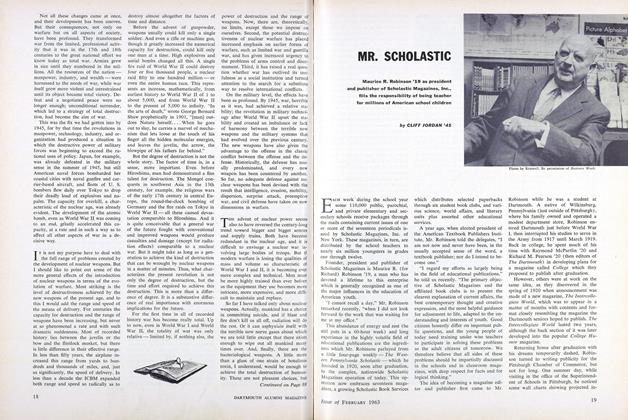

FeatureMR. SCHOLASTIC

February 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1963 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1963 By WM. W. FITZHUGH JR., DAVID D. WILLIAMS

HERBERT W. HILL

-

Books

BooksREVOLUTIONARY NEW HAMPSHIRE: AN ACCOUNT OF THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL FORCES UNDERLYING THE TRANSITION FROM ROYAL PROVINCE TO AMERICAN COMMONWEALTH

October 1936 By Herbert W. Hill -

Books

BooksA SYNOPTIC HISTORY OF THE GRANITE STATE,

February 1940 By Herbert W. Hill -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S SKIPPER

June 1944 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksYANKEE KINGDOM.

July 1960 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksAS A CITY UPON A HILL.

FEBRUARY 1967 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Article

ArticleThose Early Days of Alumni College

MARCH 1971 By HERBERT W. HILL

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE FLEET TODAY

February 1941 By A. L. DEMAREE. -

Books

BooksTHE FULBRIGHT PROGRAM: A HISTORY.

APRIL 1966 By DAVID A. BALDWIN -

Books

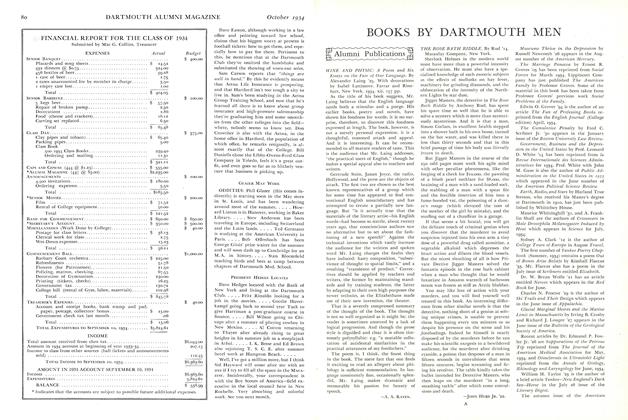

BooksTHE ROSE BATH RIDDLE

October 1934 By John Hurd Jr. '22 -

Books

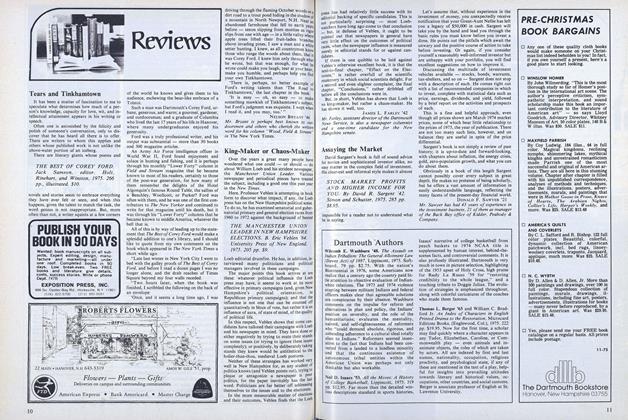

BooksTears and Tinkhamtown

November 1975 By NELSON BRYANT '46 -

Books

BooksAT THE SIGN OF THE GOLDEN COMPASS

October 1938 By RAY NASH. -

Books

BooksTHE FOUR SEASONS OF SUCCESS.

FEBRUARY 1973 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38

HERBERT W. HILL

-

Books

BooksREVOLUTIONARY NEW HAMPSHIRE: AN ACCOUNT OF THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL FORCES UNDERLYING THE TRANSITION FROM ROYAL PROVINCE TO AMERICAN COMMONWEALTH

October 1936 By Herbert W. Hill -

Books

BooksA SYNOPTIC HISTORY OF THE GRANITE STATE,

February 1940 By Herbert W. Hill -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S SKIPPER

June 1944 By HERBERT W. HILL