Part II (1898-1914) in a three-part series

BY the end of the century some great songs of Dartmouth College had evolved, a few complete, some still in an amorphous state, and more awaiting the touch of a musical wand to bring tones and harmony to written but rarely recited verse.

There was sufficient substance available to warrant the publication of a Dartmouth Song Book, and that was a task that Edwin Osgood Grover set for himself a short time after his graduation in 1894.

Grover had always been a versifier, and had contributed to the volume of Dartmouth Lyrics published in his junior year by Bertrand A. Smalley, a classmate. This book contained about 120 poems written by undergraduates during the previous decade. Many of them were later set to music, as will be indicated. Grover's companions in . this effort, besides the over-towering Hovey, included Wilder Quint 'B7, Fred Pattee '88, Ozora Davis '89, Samuel Bartlett '87, Benjamin Gillette '88, Charles Milliken '87, and Nathan Washburn '85.

All of these, with the exception of historian Wilder Quint, were recognized in the Song Book - but only two, Pattee and Gillette, through their "Twilight Song," have managed to survive the 20th century competition.

It is only proper that these early settlers on the plain of Hanover music be given the benefit of thumb-nail biographies.

Samuel Colcord Bartlett, who has been mentioned previously, had illustrious relations. He was the son of President Bartlett, for whom he was named, the brother of beloved chemistry Professor Edwin J. Bartlett, and the father of Prof. Donald Bartlett '24. The greater part of his life was spent as a missionary in Japan, and for a time he was Chaplain at Doshisha University at Kyoto. His brief claim to musical fame arose from his collaboration with A. F. Andrews in the writing of the words to "Praise of Dartmouth."

Ozora Stearns Davis was born in the town of Wheelock, Vt., which had been in controversy as to College ownership half a century before. For a while after graduation he remained in the Green Mountain area, being principal for a time of the Hartford (Vt.) High School. He later attended Hartford Theological Seminary, received degrees at Leipzig, lowa College, and Chicago Theological Seminary, of which latter institution he became president in 1909. That same year he received the honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity from his alma mater. In his junior year at Dartmouth, he too had published, along with William D. Baker '89, a collection of poems gleaned from the undergraduate publications. The purpose of this work, also titled Dartmouth Lyrics, was "to preserve the best that had been written by Dartmouth students up to 1888." In the song "Eleazar," to the tune of "Co-ca-che-lunk," he tells of Eleazar

"Calling pupils to their Hebrew With his conch shell in his hands."

Not quite as dramatic as Hovey's later references to bible, drum and rum.

Nathan Washburn 'B5 was possibly the first Dartmouth man to have joined with Hovey in the writing of a Dartmouth song. It was entitled "Dartmouth Hall" and appeared in Ditson's American College Songbook in 1882. This accomplishment, plus the fact that he was active in various campus musical organizations, was the sum total of his known musical career. He went forth from college to be a judge and an associate justice in the Massachusetts courts - and was able to send a son to Dartmouth, Kendrick H. Washburn '15.

Charles D. Milliken '87, born in Littleton, N. H., was another in the long line of Dartmouth preachers, receiving his Bachelor of Divinity degree from Yale in 1892 and finally settling in California. He was reported to be "musically inclined and possessed of an exceptionally fine voice." He united with Richard Hovey to write the first music for "You Remind Me Sweeting." Although this appeared in the First Song Book it cannot be termed a Dartmouth song. It became very popular after a new setting by F. F. Bullard and publication in sheet music form in 1900 by John Church. Fred Lewis Pattee and Benjamin B. Gillette, both of the Class of 1888, must not be dismissed lightly. Hovey was in his last year at Dartmouth when they were freshmen, but there is nothing to indicate that they had any associations with him.

Pattee came from nearby Bristol, N. H., and made many contributions to the campus publications. He was Class Day Poet, which was more than Hovey could claim. He was an educator all his life, spending 34 years at Penn State College, ending up in later years at Rollins. He was most beloved at Penn State because of his authorship of their alma mater song in 1901...He has been memorialized at that institution by the dedication of a beautiful building, the Fred Lewis Pattee Library.

Ben Gillette took up the musical profession while in college, and carried it as his shield and banner for the remainder of his life. He was born in Hartford, Vt., so came early under the Hanover influence. He was college organist and also performed the same function at St. Thomas Episcopal Church. For varying periods he was the organist at Trinity Church, Boston, St. Stephen's Church in Lynn, and the First Congregational Church in Cambridge. He wrote many religious musical settings, such as the "Te Deum" which was sung at the tenth annual festival of the parish choirs of the Diocese of Vermont. He was honored with the degree of Associate of the College of Musicians, which is proof of excellence in his field. His career came to an end with his death in Hanover, Mass., on February 9, 1933.

Pattee and Gillette joined forces to write that delightfully harmonious piece, the "Twilight Song." It has soul-satisfying close harmony, especially adaptable to four-part singing. For that reason it is rarely heard in mass gatherings, except when a few glee-clubbers sneak off into a corner for a little reminiscent vocalizing of their own. It is significant that, except for a change of a half-tone in key (which makes it easier to read) there have only been about a dozen minor note changes in sixty years of rendition. Which speaks well for the Gillette arrangement.

Omitted for no apparent reason from the fourth and fifth editions of the Song Book it was put back into circulation in 1950, where it should remain as one of Dartmouth's finest songs.

Another whose walk in life closely parallels Gillette's was Walter T. Sumner '98 who likewise played the organ at the college chapel and at St. Thomas'. His musical life appears to have been more diversified, because he also played the piano and guitar, baritone and tenor horn, double bass, and cello. He was a member of the Glee Club for four years, singing second tenor. He organized and managed the college orchestra. In his spare moments he found time to be a member of the Dramatic Club, and in his senior year was editor of The Dartmouth. His life work was in the Episcopal Church, where he achieved his highest honor as Bishop of Oregon.

Bishop Sumner's only monument to fame as far as Dartmouth songs are concerned was his setting to "Salve, Salve" - which appeared just once, in the Song Book's first edition. The words had been written years earlier by John Robie Eastman '62, who taught math at the U.S. Naval Academy and was astronomer at the Naval Observatory for 36 years. He was retired with the rank of Rear Admiral in 1898. Thereafter his alma mater beckoned and he was a Trustee of the College from 1900 to 1912.

Bertrand Smalley '94 has been previously mentioned as the publisher of one of the Dartmouth Lyrics volumes. Besides the eight poems appearing in the 1893 edition, he wrote a "Dartmouth Song," which unfortunately never had the benefit of a setting. Perhaps this is just as well, since its trite platitudes would have soon faded under the resplendence that soon dissipated the morning vapors of our musical campus.

Another flash of nostalgia came from the pen of George A. Green '98, who became a successful lawyer in New York City. As a freshman he likewise was caught in the spell of chapel and wrote the words to "Chapel Bell" which endured only briefly:

"What cuts athwart the morning air, Arousing me to daylight's glare? What makes me chew my morning steak In haste; some crullers grab, and make speedy break?

What makes me take a morning slide Across the campus, on the glide, feet denied?

CHAPEL BELL! Hmmmmm!"

The College Clock also came in for some musical comment, in a bass solo written by Harry B. Metcalf '93. He was a litterateur all his life, being managing editor of The Dartmouth, editor of the Aegis, and thereafter publisher of the Newport (N.H.) Argus-Champion until his retirement. Here again, the author outlived the poem - and the clock itself or its successor has survived them both.

Another newspaper man, Philip S. Marden '94, wrote a whimsical poem, set to music by Custance, called "The Principle's Just the Same." It deals with the difficulties encountered by Professor "Chuck" Emerson in explaining the principle of the "Cartesian Diver" to his classes in physics. After leaving the sciences behind, Marden became editor of the Lowell Courier-Citizen, served on the Alumni Council, and was a Trustee of the College from 1932 to 1942, when he was made Trustee Emeritus.

Up to this point we have attempted to cover all the songs of Dartmouth written, and we assume in use, up to the conception of the first Dartmouth Song Book. It has been difficult to draw a definitive line. Some of the principals appearing in the Song Book were not making their debut, having appeared previously in "bit parts." Others who had undertaken to supply settings now found themselves supplanted by others who, presumably, were equipped to give a more polished performance. Many of Richard Hovey's poems, which had been published as such, were extracted from the files and embellished with tunes.

The publication in 1898 of this first Dartmouth Song Book created a storm of some magnitude, with life-giving rain, minor gusts of small importance, a few resounding claps of thunder, and a suecession of rainbows that are still good conversation pieces.

The attempt has been made to include some words about everyone in the cast, so they become part of the record. This recital may have been dull reading at times - but such must be the case in a factual presentation.

We proceed now to the story of the first edition of Dartmouth Songs published by Grover and Graham at Hanover in 1898. This was bound in an olive green paper cover embellished by a design by Mr. Louis Rhead of New York City, embodying the armorial bearings of the Earl of Dartmouth. Hope was expressed in the preface that "the collection may serve to revive the general campus singing among Dartmouth students, as well as to recall for the Alumni happy memories of their own college days."

In 1894 Edwin Osgood Grover was graduated from Dartmouth. He had always been a writer of verse and he knew Richard Hovey and had published an article about him in the DartmouthLiterary Monthly entitled "Dartmouth's Laureate." Their paths were to cross many times in the ensuing six years.

For eight months following graduation Grover traveled in Europe, ranging from Algiers in Africa to the Shetland Islands north of Scotland. During the winter of 1895 he called on Hovey and his bride of about a year. Henriette Hovey, in a letter to Richard's family in Washington, gives this description of one of their meetings: "Mr. Grover came, he of the Dartmouth Lit. I seized my opportunity — my Wednesday class in which only geniuses and pupils are admitted. I tipped the wink to all, invited him to stay. Then I gave a show-off lesson. He listened with all his ears, and the first thing he said afterward was 'Do they do this in Boston?' In honor of my conscience, in spite of my modesty, I was obliged to answer 'no.' His next remark was, 'Why, they ought to have this at Dartmouth instead of that old stuff.' I smiled blandly and poured tea. They would not have a mere woman, and they could not get Richard by the time they will want him. But we mean to have it down on them some day that they have missed something." Bliss Carman echoed the same sentiment sometime later when we wrote, "One wishes he might have given a course of lectures at his own college, even if it was not yet bold enough to place him on the faculty." Long after Hovey's death, President Tucker is reported by Mrs. Hovey as saying, "We made an irretrievable mistake."

Upon Grover's return to the States he enjoyed a pleasant visit with Mother Hovey in Washington and met Hovey's son who was living with her. He spent the evening chatting about Richard and some of his friends whom she had "mothered," especially Bliss Carman with whom Hovey had collaborated to produce the Songs of Vagabondia series.

About that time Grover's older brother Frederick, Class of 1890, was Professor of Botany at Oberlin College. He introduced the younger Grover to Henry Hilton '90 of Ginn and Company, who induced him to sell high school and college textbooks in the Minnesota area.

It was in Minnesota that Grover's notion of a Dartmouth Song Book began to take form, and he began to enlist the services of persons who could edit the work and, where necessary, frame the selections. As editor he chose Addison Fletcher Andrews '78. This gentleman ended up by writing the words to five songs and the music for sixteen. Apparently his star didn't last long in its ascendancy because when the second Song Book appeared eleven years later, Andrews' name was attached to only one number, an innocuous bit titled "The Atom" and five years later it too disappeared into limbo.

Andrews was a fine musician. He had been prominent in the Glee Club, having a clear tenor voice. His most sensational feats were in the art of yodeling, which was then (and might even be today) very much of a novelty. He played first violin in the orchestra, composed dances, wrote unusual rhymes for publication, and competed on the track team in the 220-yard dash and the hop, skip and jump. No wonder his contemporaries in Hanover called him "the most versatile man in his class." He sang in church choirs for more than twenty years and was with the Schumann Male Quartette for fifteen. At various times he was manager of Carnegie Hall and the New York Symphony Orchestra (1891-1892). He was also involved in the Handel Society, and was the originator of the Manuscript Society. On the side he found time to be secretary for his uncle, Congressman A. A. Ranney '44.

One of Andrews' creations, most unusual because of its prolific use of abbreviations, is entitled "Old Dart on the Conn." It treats of Gov Wentworth John, Eleazar the Rev, Sam Occum who went to old Eng, got some Lbs from the King - and some more from Lord Dart. Other verses sing of D. Webster and Rufe Choate; the first four gratis Jim, Jack, Billy and Ben. This silly ditty ends with the warning that things are not now quite so easy and:

"If you go on a spree, or adore the fair sex,

You will get the G.B. from his Giblets, the Prex, With a Hoo-Wah, Wah-tfoo-Wah, Wah-tfoo-Wah."

THE mystery man of the Song Book was one Arthur F. M. Custance, who was the composer of fifteen of its numbers. Best known as the first framer of the "Stein Song," he also supplied the tunes for "Comrades" and the "Hunting Song" - words by Hovey. The rest were in much the same category as Andrews' contributions, dashed off on some unknown contract basis with Grover.

Custance was referred to in notes accompanying the 1950 Song Book as an English composer, and all that Edwin Grover ever had to say about him was that "he was a friend of mine, an instructor in music in the Duluth high schools." However, he deserves a better encomium than that. A bit of extended sleuthing now enables us to draw a full-length portrait of the man.

Grover encountered Custance in Duluth, where he was an instructor in Latin at the then-new Central High School. As is often the case with high school faculty members, he had a secondary assignment, director of music. This was without a doubt his own primary affection. Although born in Hereford, England, on January 28, 1866, where his father and grandfather were clergymen in the Anglican Church, he had come to Canada at the age of 25. He brought with him a rich heritage of music, because he had graduated from Brasenose College at Oxford four years before with a degree of Bachelor of Music. His stay in Canada was short, and the year 1892 found him in Duluth, where he spent the remainder of his life.

Until the music department of Central High School was established Custance voluntarily took charge of the choruses of the school and directed the music at commencement exercises. His Alma Mater Song for Central was one of the most unusual songs ever written and has survived several generations. The wife of Charles R. Bailey '21, who had Custance as "home room teacher" and Latin instructor, recalls that he took a little portable organ to all the high school football games so he could lead the students in the songs, many of which he had written.

Custance is most beloved by Duluthians for his long and faithful services as organist for St. Paul's Church. He wrote many hymns and other church music, much of which is still used in St. Paul services. On November 6, 1927 a memorial tablet was unveiled in his honor in the church chancel, and all eight of the musical numbers on the program of the ceremony were by Arthur p. M. Custance. What a lucky caprice of fate that he should have been on the spot when Grover was searching for someone to bring the lilt of music to some of Hovey's treasures.

THE impression is created, as details surrounding the first Song Book are unearthed, that it was largely a commercial venture, and not purely one of love. There was the need for bulk content with sufficient Dartmouth leaven to give the volume a strong taste of Green. The frosting between the layers, and on top, was, of course, provided by Hovey's fine poetry, in proper settings.

Hovey was at this time - and it seems eternally — in dire financial straits. He was striving desperately to find publishers for his longer works, and the relatively few verses which would later become epic at Dartmouth were "small change." Mrs. Hovey was in poor health, living in New York City, unable to contribute to the family finances through elocution lessons., or the lectures to fashionable ladies' societies on the mysteries of Delsarte, which was her specialty. Hovey, himself, was traveling from Washington to Bar Harbor to Boston and back again - in the meantime having continual correspondence with Edwin Grover concerning his - contributions to the Song Book.

Mrs. Hovey expressed grave concern in her letters about the manner of recompense which Grover was suggesting. This was, in brief, the payment of small lump sums for the copyright privileges of using certain songs. For example, she wrote to Hovey on November 5, 1897, "Don't let Barney McGee get into a songbook unless you have the right to sheet music too. You need to get known in places where they don't treat you as if you were still a freshman sowing wild oats. If you are giving these poems I shall bolt on signing off my third on Barney McGee. Are you giving them? ... If the Alumni can get all your things (and use them) in places from which you get no pay, you are throwing away a big lump. ... The object of selling outright is to have the money now. Otherwise one should take percentage, wait for it and continue to get more until the end of the copyright."

Needless to say, the glint of hard cash and the pangs of an empty stomach prevailed, and all of Richard Hovey's material in the Dartmouth Song Books was obtained by either prize money or specific payments in cash.

There is a manuscript carefully preserved in the Hovey section of the Dartmouth Archives, in Richard Hovey's own handwriting, containing the words of "Eleazar Wheelock." The date inscribed thereon is Easter Day, 1894 - the same date definitely assigned to "Men of Dartmouth." It is incomprehensible that these two masterpieces, of such different moods, could have or would have been written at the same time.

Much of the chronological data for this song has been derived from Mrs. Hovey's correspondence with Mother Hovey. Besides being an atrocious penwoman she very often would write a letter over a period of several days, or even weeks, and then either neglect to insert the date, or put in an incorrect one. So, if dates are omitted or arrived at based on the "best evidence" available, the reader may understand the reason for such apparent laxity.

It appears that "Eleazar Wheelock" was written in England at the behest of Edwin Grover. The sum of $5O is reputed to have been paid for it, but there is no information as to who paid for, or who received payment for, the setting by another stranger to the Dartmouth scene, Miss Marie Wurm.

Henriette Hovey mentions meeting "a lady at the Club to whom we took a fancy. She wished to see Richard's manuscript with reference to writing music for it. She is having some music brought out in England next month." In the midwinter of 1895 she writes again that "Marie Wurm came with the rough manuscript of 'Men of Dartmouth' and 'Eleazar.' Richard is delighted with them. Some very cultural musical ladies were here and they were enthusiastic. We had such a nice time trying the things over and arranging little spots in them."

Hovey could not have picked a better arranger so far as talent and ability went. Marie Wurm at the time was 34 years of age. Born in Southampton, England, the daughter of a German musician, she had studied at the Stuttgart Conservatory with Franklin Taylor, Clara Schumann, Joachim and Raff. She had played at the Crystal Palace at the age of 22, and in the Popular Concerts two years later. In that same year she gained the Mendelssohn Scholarship. She gave successful pianoforte recitals in London and Germany, and in 1898 established a women's orchestra in Berlin. In her later years she resided in Hannover and Berlin as a teacher, spending the last thirteen years of her life in Munich, where she died at the age of 78. She had many minor compositions published, ranging from pieces for instructional purposes to piano concertos, children's operettas, string quartets, sonatas and two- and four-hand piano arrangements.

And so the only woman to appear in our song history walks briefly across our stage. If Hovey had had his way, we might have been singing "Men of Dartmouth" to her setting, at least until Harry Wellman came along. She also wrote the first setting for "Our Liege Lady, Dartmouth," but that was later superseded by another version in the fifth Song Book.

THE "Hanover Winter Song" is of Dartmouth and for Dartmouth alone, and yet the title is the only place in the piece where there is reference to its locale. It could be based anywhere in the North Country where there are "logs on the fire," the "snow drifts deep along the road," and the "great white cold walks abroad." In consequence it is often programmed by alien choral groups as just "The Winter Song" but any college man present knows that it is the spirit of Dartmouth College that is being symbolized.

Hovey's poem was written on specific commission from Edwin Grover for $50. It was intended expressly for the Song Book, and permission was extended to advertise it as such. It likewise appeared as a poem in Along the Trail, published as a book of lyrics by Small, Maynard & Co. in 1898.

Because of its superior quality Grover decided to use the artistry of Bullard for the framing of "Hanover Winter Song," and this was quite an agreeable arrangement since it would be an excellent number for sheet music. On April 16, 1898, Bullard wrote Grover that he was submitting the manuscript. It was his opinion that the composition had turned out very well "I have taken unusual pains with it, have tried it a number of times in public, and changed and altered it until it is in the best possible form." He reported that the Apollo Club of Boston planned to use it the following season. Its Hanover premiere occurred at Dartmouth Night, September 17, 1898, when it was sung in the Old Chapel of Dartmouth Hall.

And so, in Allan Mac Donald's words, "decades before the rise of skiing, winter carnivals and the glorification of the north country, Hovey's imagination leaped to set the feeling men would some day enter. It is as if he created the present Dartmouth, the Dartmouth of myth which stands any assault of reality, a pagan, Anglo-Saxon myth of primitive living and comradeship quite unlike that of Latin piety toward Alma Mater. To have sensed that coming spirit was a flash of intuition."

There were three more of Hovey's poems that turned up in the first Song Book. These may be termed Dartmouth songs, but they were not of or about Dartmouth. One, the "Hunting Song," had music by Custance and appeared only in the Song Book's first edition. The other two were in settings by Bullard and have achieved considerable outside popularity as concert numbers in sheet music form.

Harlan Pearson '93 had a brother John Pearson in the class of 1883. He has claimed that his older brother was dubbed "Barney" in college, and that he was the subject of the famed "Barney McGee," and that this fact was a campus tradition while he was an undergraduate. Hovey thought quite a bit of this poem, because he refused to let Grover take the rights to it without retaining royalties from the sheet music. He wrote Mrs. Hovey, "I have written Grover that he can have all except Barney, for a consideration. Barney I think I can do better with." This coincided with Henriette's views, as has been mentioned previously. After all, she was to get one-third of the proceeds from the sheet music sales, an arrangement that continued even after Richard Hovey's death.

"Here's a Health to Thee, Roberts" was first copyrighted by G. Schirmer Jr. in 1897 and was also published as a bass or baritone solo by the Boston Music Company. There was no proper reason for including this toasting melody in a Dartmouth song book, and it was dropped after the third edition. The words had first appeared in Carman and Hovey's Songs of Vagabondia.

"Our Liege Lady, Dartmouth" has had a checkered career. It was first published in Along the Trail as a poem in 1891. However, an index of Hovey's works written in the poet's own handwriting gives 1887 as the date of its genesis. Marie Wurm wrote the setting which appeared in the first Song Book, and in the two editions which followed. It was in four-part harmony, full of chromatics and lilting runs - a most difficult thing to sing. In consequence, Hovey's fine words were rarely heard, and the song never was popular.

This grieved many people and finally Richard Crawford Campbell '86 decided that something should be done about it. He was a Dartmouth man through and through, having been a member of the Alumni Council (1913-1919) and having sent two sons to Hanover, Thomas P. '18 and Richard Jr. '21. The younger son, whose untimely death occurred in the fall of his sophomore year, is memorialized today by the Richard Crawford Campbell Jr. Fellowship for graduate study in English.

In February 1929 Mr. Campbell offered a prize of $1000 for the best setting for "Our Liege Lady." An able committee of judges consisted of Judge Nelson P. Brown '99, Ex-Governor Channing H. Cox '01, and Charles E. Griffith 'l5 of the music publishing house of Silver Burdett Company. The competition must have been given good publicity because over 200 manuscripts were submitted. An apparent stranger to the Hanover scene, Rob Roy Peery, was announced as the winner. Peery was a well-qualified musician, having been director of his own school of music in Salisbury, N. C. He was already well known for his male quartet compositions, and had been the composer of two popular college songs, for Oberlin and Midland College.

The new setting bore no resemblance to its predecessor with a slow andante movement, a range of only an octave, and designed to be sung in unison. Its first public interpretation was at the Wet Down exercises in 1930, when it received a great ovation.

Another entry in the contest was purchased by the College for use by the musical clubs. This rendering was by Osbourne W. McConathy and was in full harmony for orchestral use and ensemble singing. Another Hovey masterpiece had reached a final and suitable form.

HAVING partaken of the rich musical fare dished up by Hovey and served by Grover, with side dishes provided by a score of others, the appetite of the Dartmouth tribe was well surfeited for about a decade. The Spanish-American War, the depression of 1903, the emergence of intercollegiate athletics as a major campus activity, and many other factors rendered the first years of the new century a barren one for songs.

In September 1907 Edwin Grover wrote to Henriette Hovey that he was writing to Oliver H. Ditson Company in regard to the book of Dartmouth songs. He complained that they were doing nothing to push it, not listing it with their other college song books, or even keeping it on sale on their ground floor in Boston. It was his hope to re-edit the book and put it into "more popular form."

This hope must have been expressed to Harry Wellman '07 during a visit to Hanover. Wellman had been sparking Dartmouth shows with scintillating music and comedy. The end result was a second edition of Dartmouth Songs, copyright by Grover and Wellman in 1909.

In the new volume only fifteen songs were retained, and twelve more added. All but two of these remained in the indexes of Volumes 2 through 5. Five of the twelve new songs have survived the ravages of time and editors, and are in the latest Song Book. All of which speaks for the solid quality of the writers in the Classes of 1908, 1909, and 1910.

It is significant that most of the new songs appearing in the second and third editions of the Song Book were written by undergraduates, who brought to their works vitality, verve - the fresh air of campus life, words and music of action - the glories of athletic contest, the conviviality of the student body as it cheered its heroes at campus rallies and during the "peerades" to Boston and New York. This will be evidenced as we immerse ourselves in the stories behind the songs of "circa" 1910, give or take a few years.

The major domo of the whole operation, unofficially, was Harry Richmond Wellman 'O7. All through his undergraduate days he was the leading force behind the musical scenes, staying in Hanover long enough thereafter to appoint his successors who followed.

Born in Lowell, Vt., on June 7, 1881, he earned his education the hard way. He was 22 years old before he finished his preparatory work at Brigham Academy. He entered Dartmouth with almost no money and was willing to wash dishes in Commons and stoke fires in faculty homes. But he was always ready to display this friendly, sparkling half-smile that graced his outward charm and won him so many friends for the ensuing four decades.

By the beginning of sophomore year Harry had begun to find himself, or rather the College had discovered him. He was elevated to the job of checker in the grill at College Hall, after having had a successful summer at the World's Fair in St. Louis. Out there in the then "far west" he had pushed a wheel chair and cadged his way into some of the concessions where a piano player was a necessary prop. He had gone to St. Louis with Jim Wallace '07 who had been born in the Fair City. The two of them were fascinated by the Navajo Indians in their snake and eagle dances. These Indians were reincarnated in Hanover as the three dancing sons of Sammy Occom, yclept Little Big Joke, Henry Hit the Bottle, and Sammy Occom II. They were part of the cast of "The Founders" which had its debut in 1906 - the first musical show ever given in Hanover. It was Wellman's conviction that if Harvard could put on an annual Hasty Pudding Show, and Princeton could work up a yearly production with its Triangle Players, then the hay-shakers of New Hampshire should be able to come up with something worth while.

There are many interesting sidelights to the story of "The Founders" which must be left for a more complete account when the narrative of Dartmouth musical shows is written. The show was the vehicle for that perennial favorite — "Williams True to Purple" or "D-A-R-T-M-O-U-T-H." This was the finale of the show, and it must have shaken the eaves. The performance was repeated later in the spring when it went on the road as a series of vaudeville acts. The production staff was augmented by George Terrien '06, a Littleton, N. H., boy who was to make and lose a fortune in Oklahoma oil.

Harry played the piano expertly, and it was almost a nightly occurrence for him to get together in College Hall with such confreres as Paul Felt 'O6 and Nate Redlon '06 to "sing our own music." One other summer he took a job as assistant stage manager for a traveling company of "Beauty and the Beast," and about that time was considering making the stage his career. However, his mother showed up one night at a Lowell, Mass., performance and dragged him home by the ears. His only remonstrance was, "But, why shouldn't I become a second Belasco?" History does not record his mother's reply.

His impact on Dartmouth musical history as an undergraduate would have been sufficient reason for enshrinement in Dartmouth's Hall of Fame, so it is almost an anti-climax to point out that as a member of the Tuck School faculty from 1919 to 1952 he became even more beloved, achieving national recognition as an educator and counselor through artides in Collier's, the American Magazine and the Saturday Evening Post.

At the risk of being disputed we would like to make the brash statement that Harry Wellman was the friend and intimate of more Dartmouth men than any other figure in the history of the College.

DARTMOUTH songs of the 1910 era were undergraduate songs, spawned overnight, tried out on a rented upright in a dormitory room, or fingered softly on the battered baby grand in College Hall, given a dry run at the Phi Gam house when most of the brothers were engaged in less empyreal occupations, test-fired at a Glee Club concert

in Hanover prior to a western spring trip, and finally given the blast-off at an out-of-town football game. They were vigorous, spontaneous, exuberant, dashing, peppery, instinctive, overflowing. It was clearly a new era.

This was not merely a Dartmouth renaissance. It was happening all over the collegiate realm. Gone was the "hymn" type with its ivied walls, love and faith undying - "though memory fails and friends be few, we love thee still, old N.Y.U." Mellow fellowship and wassail disappeared with their foaming glasses of ale, beer or burgundy. No more logs on the fire or flowing bowls. Let's get out in the open air, for "victory or die" at Harvard, Fordham, Wesleyan and Wooster.

With two possible exceptions, the new songs of the 1909 and 1914 Song Books were those of the athletic field and hoped-for victory. Whether in defeat or victory, as the backs go tearing by, as the team goes plunging forward, here's to the team, Harvard must give in, cheer for old Dartmouth, our team's a winner, touchdown-touchdown, Dartmouth's in town again, when the green comes forth to battle. Don't know all the words? That's all right. Just keep time with the FRUMP, FRUMP, FRUMP of the bass drum and bellow the tune. No one will know the difference.

Let's get back to Hanover and review some of these new phenomena at close range, at the side of Rollo Reynolds, Walter Golde, Charles Libbey, Tom Keady, Art Wyman, Walt Rogers, Emmet Naylor, Larry Adler, Ray Wilkinson, Mose Ewing, Lyme Armes, Bob Hopkins, Rufe Sisson, Winsor Wilkinson, Warde Wilkins. What a double octet they make!

Walter Golde '10 was probably the most prolific song writer of that era. His fame is equally divided between Dartmouth songs and musical shows - from which some of these songs were lifted. To a greater or lesser degree he was involved in four Prom Shows given in the springs of 1907 to 1910 - "If I Were Dean," "The Promenaders," "The King of U-Kan," and "The Pea-Green Earl."

The third of this series is the one that interests us the most because it gave us "Dear Old Dartmouth." Rollo Reynolds '10 and Charley Libhey '10 wrote the book and lyrics, and Walter Golde wrote all of the music. During the summer following sophomore year Reynolds and Golde had tried to get some ideas together for a show while rusticating at the Reynolds farm in East Cambridge, Vt. But apparently Vermont hillsides in summer are not conducive to the writing of musical comedies, so they declared a moratorium until fall. Golde reports that "Rollie was a genius at writing lyrics, and we wrote songs rapidly, one after the other." By mid-winter everything was complete, the offering was put into competition and won the selection for that year's production. It was a conspicuous success, and the piece de resistance was "Dear Old Dartmouth," which appeared in the third act. It was encored seven times at its first performance.

During Commencement that year some of the visiting alumni led by Heinie Hobart '05 sang it on the porch of the C & G House,.and from that day forward it became a "must" for the entire College. It was introduced publicly at the Harvard game that fall where it was a great success musically, but failed inspirationally, since Harvard won the game 12-3. It did better at Princeton by bringing about a 6-6 tie. Aesthetic Harvard approved the number, and Golde reported that for the first time in his memory the Crimson stands applauded the tuneful efforts of the Dartmouth partisans.

"Dartmouth Days," which has always been a favorite in the realm of nostalgia, was also in the same Prom Show, again with music by Golde, words by Libbey. With its plain melody and words it has the faint aura of an alma mater song, but in competition would probably run a poor third to "Come Fellows" and "Men of Dartmouth." It is unfortunate that it is rarely heard in these later years, and it is questionable how many Dartmouth alumni today could sing it, or would even recognize it if they heard it.

The composition of music brought great satisfaction to Walter Golde in his early student years. His father had come up to Hanover to see the 1909 show and realized, along with his son, that music should be Walter's life work. So, after graduation, he was, sent to Vienna to study music at the Imperial Conservatory. After three years of professional training abroad he was thoroughly prepared to start a career of collaboration with singers and instrumentalists such as Mischa Elman, Pablo Casals, Richard Bonelli, Elizabeth Rethberg, Maria Jeritza, Mary Garden, and Maggie Teyte. They, and many others, used his music - and he performed with them in public and in recordings.

The first few years he toured a great deal, but later on was kept occupied in the environs of New York, where he handled all the debuts of these artists in the various concert halls. He did a great deal of coaching and, after studying "voice" all over again, qualified as a successful teacher of singing, with pupils both from the Met and the New York City Opera Company. Later, he became associated with the University of North Carolina, eventually reducing his activity to the tutelage of private pupils, while at the same time continuing with his compositions. He attained membership in ASCAP and the New York Singing Teachers' Association, and was a charter member of the National Association of Teachers of Singing.

Charles O. Libbey '10 was Rollo Reynolds' roommate. He was a fine co-worker and editor, and did much to add finesse and flourish to the work that his confreres turned out. Working behind the scenes, his light was partly obscured, but he was most assuredly one of the 1910 ensemble. He has told us through his son, Harrison Libbey '35, of the circumstances surrounding the writing of "Dartmouth Days." "Walter Golde came up to Dad's room in Middle Fayer looking for Rollie who was Dad's roommate. But Rollie was out of town. Walter was anxious to get a song written, so Dad said he'd try his hand at it. He'd never written a complete song before. It took all afternoon, but the result was 'Dartmouth Days'."

Rollo Reynolds was probably the most aesthetic member of the group. As a senior he was awarded the Hovey Poem Prize and was named Class Poet. He received his Ph.D. from Columbia in 1923 in tribute to his work in education, having at one time been principal of Horace Mann High School.

Lawrence Adler '08 wrote the music for the first Prom Show of note, "If I Were Dean." This was produced on. an improvised stage in Commons. He also produced, with Arthur Wyman 'OB, the song "Our Lady Dartmouth" which achieved fame by being included in the second Song Book. Larry was acknowledged as the musician of his class. He was accompanist for the Glee Club and sang in the College Choir. He went on to become a writer, teacher, and professional musician. While at Henderson's School for Boys in Samarcand, N. C., he composed a new setting for Hovey's "A Health to Thee, Roberts," and presented it to the Dartmouth Glee Club.

Walter C. Rogers '09 also used Art Wyman as his poet in that gridiron rouser "As the Team Goes Plunging Onward." This song must have had some emotional appeal because it appeared in four editions of the Song Book. The music was bright and had an easy lilt to it.

Although it was a fine marching song for the Band, it never achieved the popularity of three or four other gridiron tunes that will be cited later on. Similar comment might be made of Golde and Naylor's "Here's to the Team." Its music is terrific for a marching number, and only the chorus uses the words. Since, as such, they occupy only one third of the 97 bars in the piece they may be tolerated, if they could, by chance, be memorized. Golde apparently was aware of the song's defects, because in a letter to Harry Wellman on September 10, 1923 he admitted that "the piece is a flivver, and it wouldn't offend me in the least if you thought it best to leave it out altogether." The suggestion failed to register properly, since it still appeared in several subsequent editions.

In any event, the appearance of these songs indicates the proliferation that was present on the campus in that era. Such creativity has not been seen since.

ONE of the liveliest of the football perennials is "As the Backs Go Tearing By," regularly followed by "Glory to Dartmouth" with which it meshes perfectly. The lyricist of the former was John Thomas Keady '05, but the setting has been variously attributed to Carl W. Blaisdell or Charles W. Doty, neither of whom were Dartmouth men.

On August 21, 1917 Oliver Ditson published the Khaki Song Book which contained a piece entitled "When the Boys Go Marching By." The words were reputed to be by Charles Dasey and the music by Carl Blaisdell. This was incorrect. The truth is that this song was completely written (both words and music) by Charles W. Doty, copyright 1901. The chorus went as follows:

When the boys go marching by On their way to do or die, Many sobs and many cheers Mingle with the falling tears When the boys go marching by.

Keeping step as martial strain Echoes back a sad refrain To the mother old and kind And the girl he leaves behind When the boys go marching by.

Since no biographical reference to Charles Doty can be found in the standard sources, it is possible that the name is a pseudonym.

As can be seen from the above, Keady did a fine job of paraphrasing to make a football song out of this rather bellicose rhyme. At the time he did it, Carl Blaisdell's band was regularly employed by the College for commencement and other social events. Keady apparently prevailed on Blaisdell, who came from his home town, to rearrange the music to suit his own words.

Tom Keady was no poet laureate, and never aspired to any such fame. He was a tremendous football player and athletic coach who just happened to dash off a nine-line bit of doggerel, attached some music that was animated and brisk, and handed the combination on to posterity to be used before, during and after every gridiron victory, tie or defeat. Tom was Ail-American at Hanover and thereafter made football coaching his profession. He was head coach for nine years at Lehigh and four years at the University of Vermont, was in charge of all athletics at the Quantico Marine Base for seven years, added three more years in football at Western Reserve, and, in his final years of physical activity, came back to New England as athletic director at Lowell High School. He has said that he coached 3,200 athletes, and at one Christmas received holiday greetings from more than 3,000 of them. More than 36 years after he had left Lehigh he was called back to receive a bronze plaque in belated recognition of his services to that institution. His lone contribution of poesy to Dartmouth will long sustain his memory.

Another musical great during the 1910-1914 era was Moses Courtwright Ewing '13, known to his classmates as Mose, and to many students and pupils as "Prof." He was probably the most prolific writer of settings that Dartmouth ever had, with the span extending from the music for the "Touchdown Song" written in 1910 right up to 1940 when he wrote the organ arrangement for "Dartmouth Undying." Fortunately, all of his manuscripts are now in the possession of the Music Department of the College, many having been given prior to his death, and the remainder by his widow, Bertha Ewing. They should prove a never-failing fount of remembrance when Dartmouth musical aficionados have a desire to observe, firsthand, the ebullience of a musical mind with his college as the prime motive. It would appear that he was also quite a lyricist, because about half of his works indicate both "words and music by M. C. Ewing." His subjects varied from football (Hit Them Again for Dartmouth, The Thunder of Your Cheers, Dartmouth Will Win) to history (Samson Occom, Rollins Chapel) and affection for the College (Men of Dartmouth Gather Round, Vox Clamantis in Deserto, The Spirit of Dartmouth).

Ewing must have felt that if he were to follow a career in music some other campus could provide a broader experience, because he transferred to McGill after his junior year. His degree of Mus.B. was not received there until 1920, the years in between being used to buttress his finances as orchestra conductor and arranger of music at Keith's Imperial Theater in St. John, New Brunswick. However, at the Princeton football game, played at the Polo Grounds in his sophomore year (1910), he heard the first public performance of the "Touchdown Song," which so inspired the Princeton team that they won 6-0.

Another baccalaureate degree in music was awarded to him by the Royal College of Church Music in London, England, where he was a member of the Royal College of Organists. Back in St. John he was president of the St. John Musicians Protective Association. In 1921 he wrote the words and music for a comic opera "Salvagi" which had its premiere on February IS of that year. Then the Southland called, and in 1931 we find him as Professor of Music at the Berry Schools and College at Mt. Berry, Georgia. As evidence of his versatility, he was assistant professor of both Greek and German. In 1936 he wrote a textbook on Rudiments of Music and also a Short History of Music. For a time he returned to New England, but was back at Mt. Berry again by 1951. Here, once more, his musical life was full, as director of choirs, glee clubs, quartets, orchestras and bands for several schools, in addition to Berry. This extremely active life finally exacted its toll because, after several heart attacks he succumbed in the Rome (Ga.) General Hospital on January 24, 1958, at the age of 69. And now the granite of New Hampshire keeps a record of his fame.

Another exceptional combination of talent appeared in the peaceful half of the World War I decade, when Henry Lyman Armes '12 and Robert Carl Hopkins '13 appear on our stage.

In the autumn of 1911 there was an offer of a cash prize for a "peerade" song. Bob Hopkins had produced a good march tune, and with less than 24 hours to go he put pressure on Lyme Armes to write some appropriate words. Hour after hour Bob pounded out the melody and rhythm on an old battered piano in Wheeler Hall, and then left Lyme to "an endless round of humming, whistling, fretting, fuming, with occasional bursts of scribbling that served no purpose save to fill the wastebasket."

Lyme continues his narrative: "The whole day and the evening - total loss! I had an important quiz next day, but by that time Hopkins' hypnotic tune wouldn't let up on me. Around midnight, I tore the last uninspiring scribble off the yellow pad under my tin lampshade, set my alarm for an early-morning study period - went to bed dog-tired, dimwitted - and probably still hypnotized.

"When I turned out next morning, there on that yellow pad - in my own pencil-scribbling, were all the words of 'Dartmouth's In Town Again' to fit Bob's blessed old march tune - just as they were turned in for the College Hall mass meeting that night, the tryouts, just as they were printed in The Dartmouth."

Lyme Armes has a couple of complaints in connection with this intriguing episode. One is that as far as he can recall they never saw the prize money. The other is that the original words were and always have been "We have a Dartmouth team, and say." That line never did end with "hoorah," as footnoted in the 1950 Song Book. Also, the original second line was "Thunder the old refrain" instead of "Echo the sweet refrain" as it appeared in the fourth edition. For a generation or so, in consequence, there may be some confusion in the bleachers, with half the crowd "echoing sweetly" and the other half "thundering oldly."

The acme of satisfaction came to the co-authors of this dynamic piece on the afternoon of November 4, 1961 when, on the 25th anniversary of the song's genesis, over a national TV and radio network thousands of Dartmouth adherents heard and sang it, as it was played in the Yale Bowl during the midgame ceremonies. May its echoes and reverberations never cease as long as two or more fellows get together.

As a bit of side information, Lyman Armes is most proud of the fact that he can claim a remote relationship to Richard Hovey. His father, the Reverend Arza H. Armes was a classmate of Hovey's, before going to Andover Theological Seminary, where he came under the tutelage of President-to-be Tucker. In Andover he married Blanche Spofford Poor who was a great-grandchild of a Spofford, who, at the same time, was the great-grandfather of Richard Hovey.

Robert Hopkins, brother of Ernest Martin Hopkins '01, was a talented musician. He never learned to read music but he played' beautifully by ear. He loved to sit at the piano and improvise. During his years at Worcester Academy he developed an original tune which he never used - always tucking it away in the back of his brain to use some day for something special. It finally emerged as "The Cardigan Hymn," composed for the dedication of the chapel at Cardigan Mountain School where he was an original incorporator, the first vice-president, and a life-long trustee. He did not live to hear it sung at the dedication because he died after a short illness on January 29, 1962. He was buried in the country cemetery at Perkinsville, Vt., near the snow-swept slopes of Mt. Ascutney.

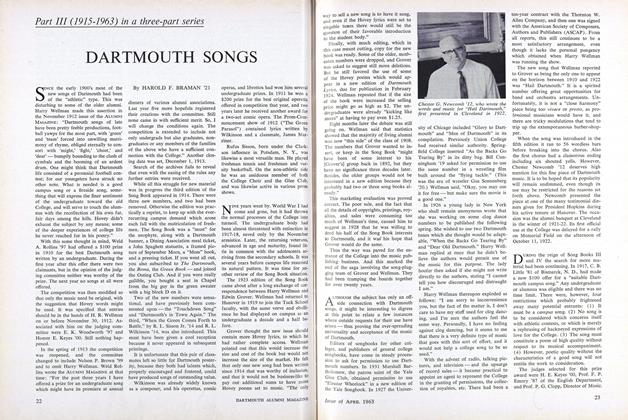

The words of "Eleazar Wheelock" in Hovey's handwriting. The date,the same as for "Men of Dartmouth," is believed to be inaccurate.

"The Founders" in 1906 introduced the song "Williams True to Purple."

"Men of Dartmouth" was a rousing finale for "The Promenaders" in 1908.

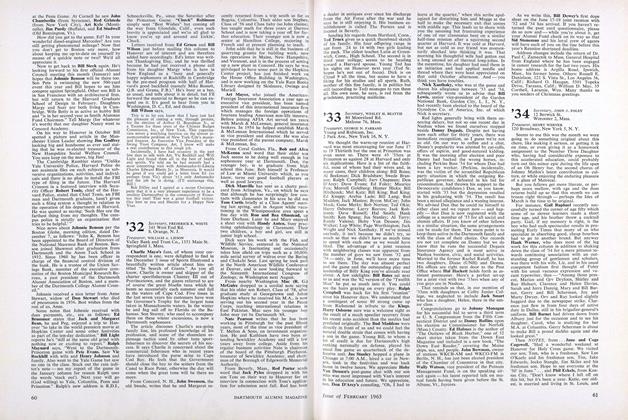

The late Harry R. Wellman '07, a brightstar in the history of Dartmouth songs,shown at Tuck School where he was amember of the faculty from 1919 to 1952.

Three classmates of 1910 and the songs they wrote as undergraduates.

Dartmouth's two most popular football songs and pictures of the men who wrote thewords while undergraduates, Keady in 1904 and Armes in a 1911 song contest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

February 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND HISTORY

February 1963 By LOUIS MORTON -

Feature

FeatureMR. SCHOLASTIC

February 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1963 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1963 By WM. W. FITZHUGH JR., DAVID D. WILLIAMS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

February 1963 By JOHN J. FOLEY, HENRY WERNER

HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

JANUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

APRIL 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fated Morning

FEBRUARY 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

APRIL 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

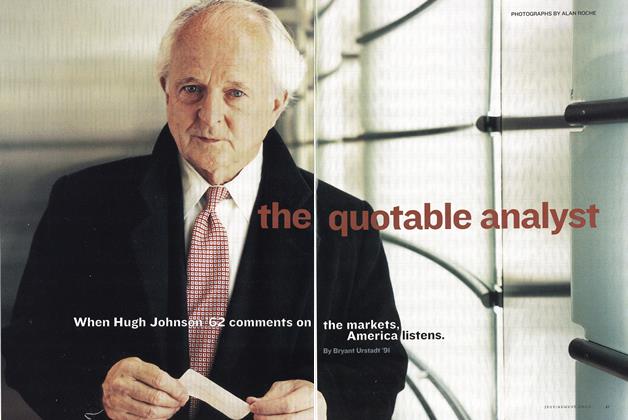

FeatureThe Quotable Analyst

July/Aug 2002 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

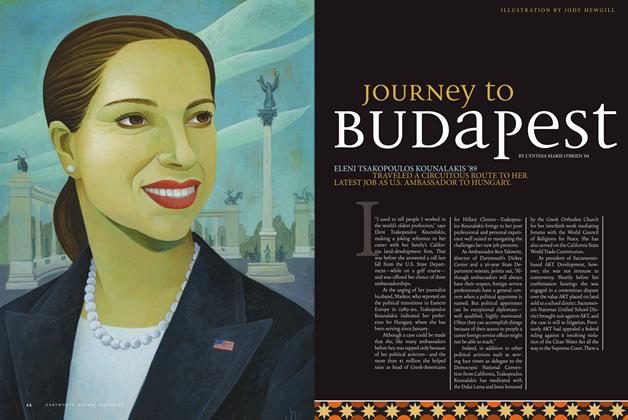

FeatureJourney to Budapest

Nov/Dec 2010 By CYNTHIA MARIE O'BRIEN ’04 -

Feature

Feature"As I Remember..."

January 1960 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThey're Putting the D in Debating

April 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Sept/Oct 2007 By Kristine Keheley '86