By PageSmith '4O. New York: Alfred A. Knopf,1966. 332 pp. $6.95.

Many attempts have been made to explain American history, notably that by Turner some 75 years ago with the theory of the influence of the frontier. Once the accepted explanation, it was challenged by some who saw the American way coming out of the cities, or by others who preferred to think of changes caused by people moving to the cities, to the suburbs, to anywhere but not just to Turner's frontier.

Now Mr. Smith, the distinguished author of John Adams, and head of Cowell College at Santa Cruz, offers another explanation in the influence of the small town, as it started in the east and spread westward. In doing so, he speaks primarily of what he calls the colonized town, created through the deliberate acts of some cohesive group, and of the covenanted town, existing with some idea of compact among its inhabitants, with each other and usually with God. In such a town, he says, most Americans lived down to the start of the present century, and so it becomes important to find out what the towns were like in order to know why we are the way we are today. Throughout his book, Mr. Smith constantly raises interesting ideas, and offers interesting answers to some of them. The temptation to write an extensive review testifies to that statement, and there can be no doubt that much more attention should be paid by historians to the small towns. Here, in an exploratory way, Mr. Smith has read widely, and offers much.

Since he also says he is offering only conjectures and hypotheses, it is perhaps unfair to take any issue with them. He does insist that the small town was "the basic form of social organization experienced by the vast majority" down to 1910 or so. Certainly one might also say that till well into the nineteenth century most Americans lived on farms, and while in some ways farm life and small town life were alike, in many ways they were not, a point Mr. Smith had some trouble with in Chapter X.

Indeed, the need for further study of the town is, in a way, clearly shown by the whole book, which seems to me to alternate between genuine perception of what small towns were like, and real open spaces. For example, the chapter on town politics is not quite right to the eye of anyone who has seen even Hanover politics for 40 years, nor does Mr. Smith refer to such obvious sources as Grant's outstanding study of Kent, Connecticut, or Labaree's of New buryport, or Powell's on Sudbury.

In a chapter on temperance, he has Matthew Patten of Bedford, New Hampshire, drinking "enormous quantities" of rum, because he bought roughly a quart a week all fall and nineteen quarts on March 7. Even in New Hampshire a town leader had to provide drinks on Election Day, and in some places around here still does.

As a final point, the towns considered are New England towns, here and as New England spread west, and Mr. Smith so states. This does raise the question of the southern town and its influence as it too went west. But this is merely one more question raised by the book, and hopefully all will be answered, if not by Mr. Smith then by others stimulated by him to accepting the thesis that the small town, as well as the frontier and the city, had a part to play in our history.

Professor of History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

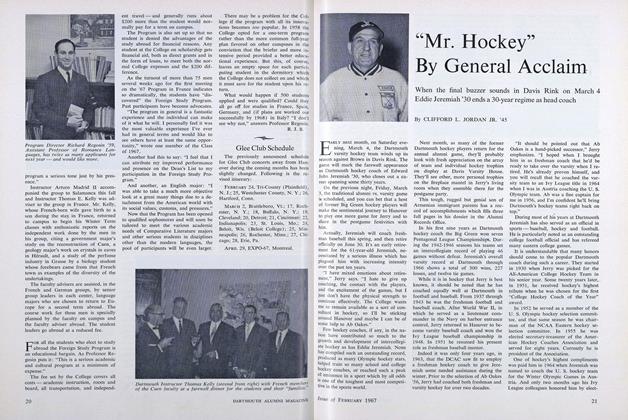

Feature"Mr. Hockey" By General Acclaim

February 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

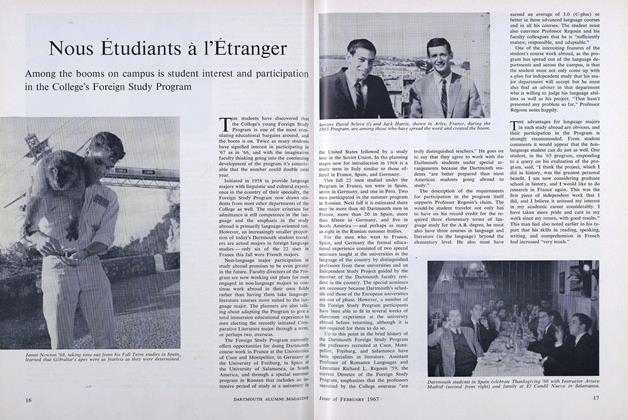

FeatureNous Étudiants à l'Étranger

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureMammalogist

February 1967 -

Feature

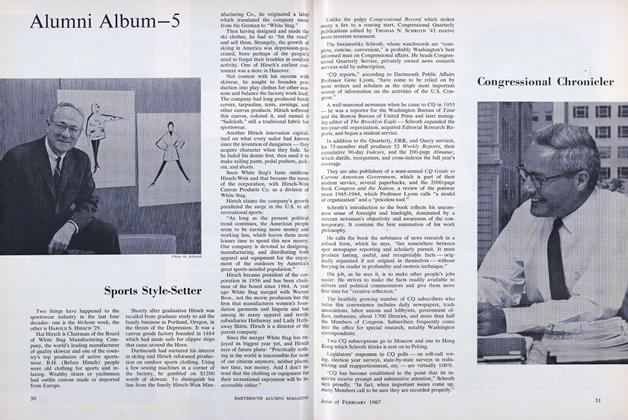

FeatureSports Style-Setter

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureCongressional Chronicler

February 1967

HERBERT W. HILL

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

February 1940 -

Article

ArticleFifth Hanover Holiday

February 1941 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksTHE UNITED STATES.

June 1954 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksDEMOCRACY IN THE CONNECTICUT FRONTIER TOWN OF KENT.

October 1961 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksCOUNT RUMFORD: PHYSICIST EXTRAORDINARY.

APRIL 1963 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksTRAVELS IN NORTH AMERICA IN THE YEARS 1780, 1781, and 1782.

MARCH 1964 By HERBERT W. HILL

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Bio Bookshelf

Sept/Oct 2004 -

Books

BooksSOLDIERS AND SCHOLARS: Military Education and National Policy

March 1957 By DONALD H. MORRISON -

Books

BooksACCRETIONS OF A MINOR NATURALIST

October 1945 By Douglas E. Wade. -

Books

BooksPEN-DRIFT: AMENITIES OF COLUMN CONDUCTING

APRIL 1932 By F. L. Childs -

Books

BooksGUERNSEY CENTER MOORE FOUNDATION LECTURES

April, 1923 By FRANK MALOY ANDERSON -

Books

BooksTHE NATURE WRITERS, A GUIDE TO RICHER READING

February 1939 By Robert McKennan '25