PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

A COLLEGE or university in a democracy has a number of responsibilities, and among them, it seems to me, is the responsibility to society to prepare its students for the duties of citizenship in a nation that has become the leader of the free world. This is really what the Great Issues Course is about and this is why Dartmouth has on its faculty - one of the few schools in the country that does - a historian like myself whose specialty is the study of war. Not war in the technical sense of how to fight it - that is the job of the soldier - but war in its broadest social and political context. My presence here on this campus is a recognition of the importance of the study of war as a political and social institution, and of Dartmouth's conviction that a knowledge of the nature of war and its relationship and impact on the whole fabric of our society is essential to an understanding of the world today and to the performance of your duties as citizens and potential leaders in the nation.

There is another reason why you as civilians should know something about military affairs and that is that war is essentially a civilian activity. What I mean by this is that war like diplomacy is an activity of the state and its function is to further the policy of the state. Its essence therefore is political; the political authorities retain control over it not only in peacetime but even after hostilities have begun. Strategy is the instrument of policy; the soldier, the servant of the statesman. It is no accident that the Founding Fathers of the Republic made the President, a civilian, the Commander in Chief, and that every successful President has exercised this function boldly and firmly.

There is no question that war, no matter how you define it, is one of the great issues, if not the greatest issue of our time. It meets all the criteria that Archibald MacLeish, in one of the first G. I. lectures, laid down for a great issue - historical depth, current timeliness, and projection into the future. The first of these, historical depth, is uniquely the function of the historian, but there is real doubt in these troublesome times that a knowledge of the past has any relevance to the problems of war and peace in the present, or that it can contribute to a solution of these problems in the future. The character of war, it is said, has altered so radically since World War II that the study of military history not only has no lessons for us today, but may even be harmful if it continues to be used as it has in the past to train military men in the exercise of their profession. Besides, there are those who oppose the study of war because they abhor it in all its aspects. Believing war evil, they deplore its study as a human activity that were better left untouched - perhaps like prostitution.

These are curious arguments. They are essentially anti-intellectual, and represent opposition to the pursuit of knowledge because the subject is unpleasant or bad. We all hate war for its waste and destructiveness, but to assert we should not study it for that reason is to say the best way to fight a disease is to ignore it. Besides, to accept this kind of reasoning would pretty well put me out of business as a military or any other kind of historian, and I am not yet quite ready to give up. Nor do I have to, for history is a particularly hardy plant and has flourished since the days of Herodotus and Thucydides - both of whom, incidentally, were military historians. I am not alarmed, therefore, that we will go out of business and that history courses will no longer be taught because of the claim that they no longer have any relevance. And the reasons why I think so are important because they relate not only to the nature of history but also to the purposes of a liberal arts education.

We do not study history, or any of the humanities, because of its utility or because it can teach us how to perform a job or tell us what to do. History is not an exact science. It is the record of man's past and we study it partly out of curiosity, partly out of a deep instinct to search out our origins, and partly because we feel we should know where we have been to get some idea about where we are going. It is a record that the historian is constantly rewriting, using the strictest rules of evidence and with the highest regard for established facts, but always within the context of his own times. That is why it is always being rewritten. History can tell us much, but it cannot predict the future exactly. What it can do is produce generalizations about past events that may reasonably be expected to apply in a general way to similar situations, with due allowance for the uniqueness of events. This is a great deal, but it is not prophecy.

Let me give you an example or two. One often hears these days the assertion that arms races lead to war, or that war is always preceded by arms races. How does this stack up against the historical facts?

Between 1840 and 1941 there were twelve arms races involving the great powers of Europe and America, some on land, some on the sea, and at least one in the air. Of these, only five can be said to have ended in war in the sense that the race was still on when hostilities began. Furthermore, three of the wars in this period - the Franco-German War of 1870, the Riisso-Turkish War of 1877, and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 — were not related to arms races at all. The longest arms race of the period, that between England and France for naval supremacy, never resulted in hostilities and was finally ended by mutual consent in the Entente Cordiale of 1904. Between 1916 and 1930, England and the United States also vied for naval supremacy, a contest that both abandoned in the face of economic depression and the subsequent threat from Germany and Japan.

On the basis of the historical record, therefore, one can show that there have been wars without arms races, and arms races without wars. To assert that arms races lead to war is simply not correct. They may, but that is as far as we can go on the basis of the record.

Historical experience can be applied also to other aspects .of the nuclear age. It has been suggested, for example, that nuclear weapons should be prohibited, as was poison gas after the first World War. If it could be done for poison gas, why not for nuclear bombs which are much more terrible? The trouble with this argument is that history tells us that no weapons have been successfully banned from use, unless they were at least as disadvantageous to the user as to his intended victim. The crossbow, for example, could never be abolished, although every effort was made to do so. The Second Lateran Council in 1139 forbade its use, except against infidels, and called it "a weapon hateful to God and unfit for Christians." Yet it continued to be used throughout most of Europe, except in England where the longbow was preferred.

Similarly with gunpowder, which the Church tried to ban and which outraged all the canons of chivalric warfare. One medieval knight had the hands of captured musketeers cut off before killing them, and Cervantes decried "the devilish invention of artillery" that enabled a "base cowardly hand to take the life of the bravest gentleman." And in a more recent day, the airplane too was viewed as a barbaric instrument of war, striking civilians and soldiers indiscriminately; and efforts were made to restrict its use as a military weapon. But like gunpowder and the crossbow, it was considered the ultimate weapon and no one would give it up so long as he thought he could gain some advantage from its use.

It may be that our hope for the future lies in the fact that there is no theoretical upper limit to the explosive force of the nuclear bomb. This being the case, the destructive power of the bomb may reach such a point - some claim it already has - that its use not only will serve no purpose but will destroy the user. When both sides believe this, then perhaps it will be possible to outlaw nuclear weapons or to limit them in some way.

IT is a truism to say that we are living today in the midst of a revolution in military technology. The introduction of nuclear weapons, long-range missiles, and space vehicles has had an enormous impact on war, introducing an entirely new element into international relations. Mankind, it is said, has reached one of the turning points of history and is moving in an entirely different direction - and at breakneck speed.

For historians, who view revolutions in a somewhat longer perspective than most, this attitude is a familiar phenomenon. Every revolutionary age tends to assume that it has broken completely with the past and has embarked on a new era in history. Actually, no revolution ever cuts its bonds completely with the past. There is continuity as well as change in history, and revolutions occur within a specific political and social context. As a matter of fact, they can only be understood in terms of the past they seek to change.

So it is with the present revolution in military technology. It cannot be understood all by itself; it is the culmination, or rather the most recent stage in a revolution in warfare that began almost 200 years ago. This revolution may be said to consist of four revolutions or, more accurately, of four overlapping and interrelated movements - one in manpower,

one in economics, one in science and technology, and the last in manage ment and organization. The first produced the mass armies of the 19th and 20th centuries; the second the means to supply, feed, and move these armies while at the same time releasing more men for military duty. Developments in science and technology led to a revolution in weaponry and a steady increase in firepower that has enormously increased the capacity of destruction. And the revolution in the techniques of management has made it possible, through military staffs and civilian agencies, to mobilize these resources in men, weapons, and production for the purposes of making war.*

Not all these changes came at once, and their development has been uneven. But their consequences, not only on warfare but on all aspects of society, have been profound. They transformed war from the limited, professional activity that it was in the 17th and 18 th centuries to the great national effort we know today as total war. Armies grew in size until they numbered in the millions. All the resources of the nation — manpower, industry, and wealth - were harnessed to the needs of war, while war itself grew more violent and unrestrained until its object became total victory. Defeat and a negotiated peace were no longer enough; unconditional surrender, which led to a strategy of total destruction, had become the aim of war.

This was the fix we had gotten into by 1945, for by that time the revolutions in manpower, technology, industry, and organization had produced a situation in which the destructive power of military forces was beginning to exceed the rational uses of policy. Japan, for example, was already defeated in the military sense in the summer of 1945, but still American naval forces bombarded her coastal cities with naval gunfire and carrier-based aircraft, and fleets of U. S. bombers flew daily over Tokyo to drop their deadly load of explosives and napalm. The capacity for overkill, a characteristic of the nuclear age, was already evident. The development of the atomic bomb, even as World War II was coming to an end, greatly accelerated this capacity, at a rate and in such a way as to affect all other aspects of war in a decisive way.

IT is not my purpose here to deal with the full range of problems created by the development of nuclear weapons. But I should like to point out some of the more general effects of the introduction of nuclear weapons in terms of the evolution of warfare. Most striking is the level of destructiveness achieved by the new weapons of the present age, and to this I would add the range and speed of the means of delivery. For centuries the capacity for destruction and the range of weapons have been increasing, but never at so phenomenal a rate and with such dramatic suddenness. Most of recorded history lies between the javelin or the bow and the flintlock musket, but there is little difference in their effective range. In less than fifty years, the airplane increased this range from yards to hundreds and thousands of miles, and, just as significantly, the speed of delivery. In less than a decade the ICBM expanded both range and speed so radically as to destroy almost altogether the factors of time and distance.

Before the advent of gunpowder, weapons usually could kill only a single soldier. And even a rifle or machine gun, though it greatly increased the numerical capacity for destruction, could kill only one man at a time. High explosives and aerial bombs changed all this. A single fire raid of World War II could destroy four or five thousand people, a nuclear raid fifty to one hundred million — or even the entire human race. This represents an increase, mathematically, from earliest history to World War II of 1 to about 5,000, and from World War II to the present of 5,000 to infinity. "In the arts of death," wrote George Bernard Shaw prophetically in 1901, "[man] outdoes Nature herself.... When he goes out to slay, he carries a marvel of mechanism that lets loose at the touch of his finger all the hidden molecular energies, and leaves the javelin, the arrow, the blowpipe of his fathers far behind."

But the degree of destruction is not the whole story. The factor of time is, in a sense, more important. Even before Hiroshima, man had demonstrated a fine talent for destruction. The Mongol conquests in southwest Asia in the 13th century, for example, the religious wars of the early 17th century in central Europe, the round-the-clock bombing of Germany and the fire raids on Tokyo in World War II - all these caused devastation comparable to Hiroshima. And it is quite conceivable that a general war of the future fought with conventional and improved weapons would produce casualties and damage (except for radiation effects) comparable to a nuclear war. But it might take as long as a generation to achieve the kind of destruction that can be wrought by nuclear weapons in a matter of minutes. Thus, what characterizes the present revolution is not only the degree of destruction, but the time and effort required to achieve this destruction. This is more than a difference of degree. It is a substantive difference of real importance with enormous implications for the future.

For the first time in all of recorded history war has become really total. Up to now, even in World War I and World War II, the totality of war was only relative - limited by, if nothing else, the power of destruction and the range of weapons. Now, there are, theoretically, no limits, except those we impose on ourselves. Second, the potential destructiveness of nuclear warfare has placed increased emphasis on earlier forms of warfare, such as limited war and guerilla war, and has given increased urgency to the problems of arms control and disarmament. Third, it has raised a real question whether war has outlived its usefulness as a social institution and turned attention to the search for a substitute way to resolve international conflicts.

On the military level, the effects have been as profound. By 1945, war, horrible as it was, had achieved a relative stability; the revolution in military technology after World War II upset the stability and created an imbalance or lack of harmony between the terrible new weapons and the military systems that had evolved over the previous century. The new weapons have also given the advantage to the offense in the classic conflict between the offense and the defense. Historically, the defense has usually predominated, and every new weapon has been countered by another. So far, no adequate defense against nuclear weapons has been devised with the result that intelligence, evasion, mobility, dispersion, surprise attack, preemptive war, and civil defense have taken on new dimensions in warfare.

THE advent of nuclear power seems also to have reversed the century-long trend toward bigger and bigger armies and supply trains. Both have become redundant in the nuclear age, and it is difficult to envisage a nuclear war involving large bodies of troops. But if modern warfare is losing the qualities of mass and volume so characteristic of World War I and 11, it is becoming ever more complex and technical. Men must be more highly trained than ever before as the equipment they use becomes more intricate, more expensive, and more difficult to maintain and replace.

So far I have talked only about nuclear weapons. Actually, mankind has a choice in committing suicide, and if blast and fire don't kill us all off, radiation will do the rest. Or it can asphyxiate itself with the terrible new nerve gases about which we are told little except that there exists enough to wipe out all mankind many times over. And, finally, there are the bacteriological weapons. A little more than a glass of one strain of botulinus toxin, I understand, would be enough to achieve the total destruction of humanity. These are not pleasant choices, but it is more than interesting, I think, that one reads virtually nothing about gas or bacteriological warfare. So far as the public is concerned, their existence seems almost to be ignored. It is almost as though both sides by common consent have agreed not to talk about them.

WELL, where does all this leave us? We have tried to put the revolution in military technology into perspective and to indicate how a knowledge of history can be useful to the present. What about the future? Can we say anything about what is to come on the basis of the past? Historians are notoriously poor prophets - witness Karl Marx, Oswald Spengler, and, some would say, Arnold Toynbee - and war is a particularly treacherous field for prophecy. It is, to paraphrase Clausewitz's words, an unexplored sea, full of rocks which man may sense but never see and round which he must steer on a dark night.

Rather than venture into the dark sea of prophecy, therefore, I would only remind you that war has in the past served the purpose, for good or evil, of resolving conflicts between groups and societies when all other means had failed. Thus far, man has failed to devise any other institution or organization to achieve this, though the need for one obviously is more important, more urgent now than ever before. Unless the nature of man or of social organization is altered, it is folly I think to hope for the abolition of war without finding some means to resolve conflict. Further, war has rarely been waged without substantial restraints that mitigated its violence. Almost always, it has had rational and limited objectives related to the policy of the state. What was disturbing about the last two world wars was the development of the capacity for destruction so that it threatened to exceed ra- tional limits. Thermonuclear weapons and intercontinental missiles have carried this development to its ultimate point so that, theoretically, the entire civilized world could be destroyed by existing weapons. In this situation, it seems to me there is no choice but to return to the limited wars and conventional weapons of an earlier period until mankind can find a substitute for war itself. How this is to be done, while preserving our security and way of life, is perhaps the greatest issue of our time.

* Professor Morton in his lecture developed in detail the effects of these four revolutions on the evolution of warfare in the last two centuries.

PROFESSOR MORTON'S ARTICLE is adapted from his January 7 lecture in the Great Issues course. One of the country's foremost military historians, he served with the U. S. Army in the Pacific in World War II and later became deputy chief historian for the Department of the Army, supervising the preparation of twelve volumes on The War in the Pacific and writing two of them himself. His book The Pacific War:Strategy and Command has just been published, joining his books on The Fall of thePhilippines and Command Decisions in World War II (co-author). Professor Morton has recently accepted the general editorship of a 16-volume series for Macmillan on wars of the United States, and this year, under a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, he will begin an extended study of the World War II period with emphasis on the major problems that are relevant to present and future military policy and strategy. He came to Dartmouth in 1960 from the University of Wisconsin and earlier taught at C.C.N.Y. and William and Mary. In 1959 he received the Rockefeller Public Service Award for research in national security policy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

February 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureAND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

February 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

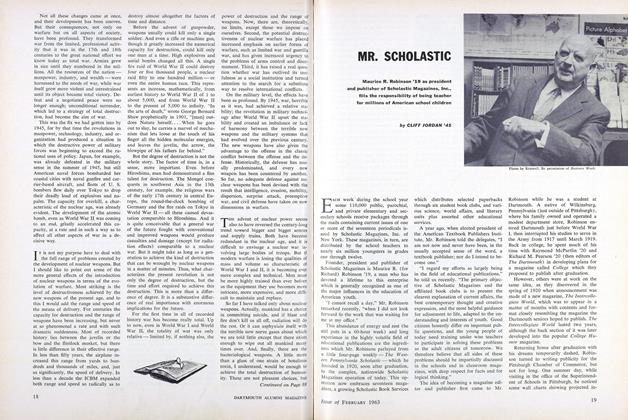

FeatureMR. SCHOLASTIC

February 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1963 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1963 By WM. W. FITZHUGH JR., DAVID D. WILLIAMS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

February 1963 By JOHN J. FOLEY, HENRY WERNER

LOUIS MORTON

-

Books

BooksTHE GETTYSBURG CAMPAIGN, A STUDY IN COMMAND.

DECEMBER 1968 By LOUIS MORTON -

Books

BooksMILITARISM, U.S.A.

OCTOBER 1970 By Louis Morton -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN CAMPAIGNS OF ROCHAMBEAU'S ARMY 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783. Vol. 1. THE JOURNALS OF CLERMONT-CREVECOEUR, VERGER, AND BERTHIER. Vol. 2. ITINERARIES AND MAPS AND VIEWS.

MARCH 1973 By Louis Morton -

Books

BooksTHE WAGES OF WAR 1816-1965: A STATISTICAL HANDBOOK.

MARCH 1973 By Louis Morton -

Books

BooksJUSTICE UNDER FIRE: A STUDY OF MILITARY LAW.

July 1974 By LOUIS MORTON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

MARCH 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureHONOR: The Vanishing Principle

February 1975 By JAMES A.W.HEFFERNAN -

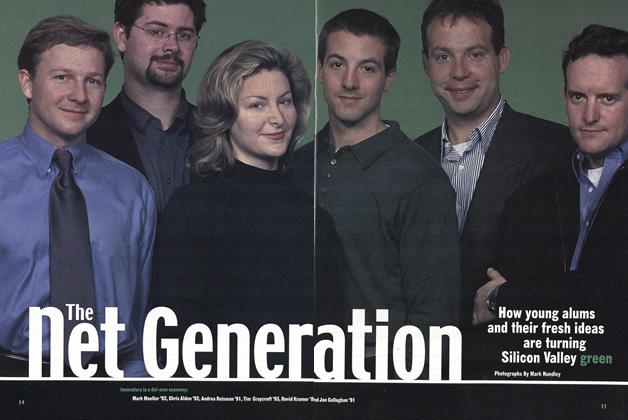

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Net Generation

April 2000 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

JUNE 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYTelevision’s Wonder Woman

MARCH | APRIL By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Study Urges ROTC Program Changes to Meet Nation's Needs

MAY 1959 By JOHN HURD '21

LOUIS MORTON

-

Books

BooksTHE GETTYSBURG CAMPAIGN, A STUDY IN COMMAND.

DECEMBER 1968 By LOUIS MORTON -

Books

BooksMILITARISM, U.S.A.

OCTOBER 1970 By Louis Morton -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN CAMPAIGNS OF ROCHAMBEAU'S ARMY 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783. Vol. 1. THE JOURNALS OF CLERMONT-CREVECOEUR, VERGER, AND BERTHIER. Vol. 2. ITINERARIES AND MAPS AND VIEWS.

MARCH 1973 By Louis Morton