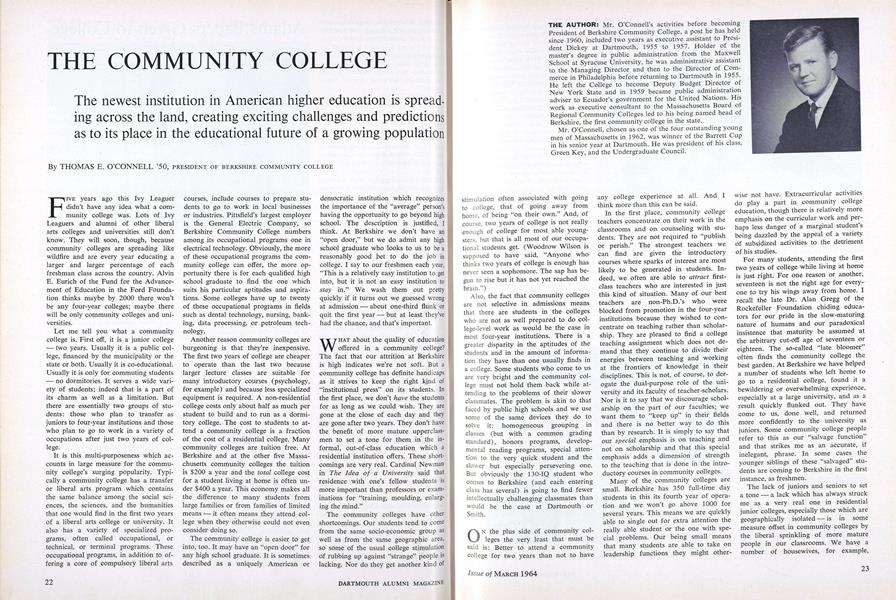

The newest institution in American higher education is spreading across the land, creating exciting challenges and predictions as to its place in the educational future of a growing population

PRESIDENT OF BERKSHIRE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

FIVE years ago this Ivy Leaguer didn't have any idea what a community college was. Lots of Ivy Leaguers and alumni of other liberal arts colleges and universities still don't know. They will soon, though, because community colleges are spreading like wildfire and are every year educating a larger and larger percentage of each freshman class across the country. Alvin E. Eurich of the Fund for the Advancement of Education in the Ford Foundation thinks maybe by 2000 there won't be any four-year colleges; maybe there will be only community colleges and universities.

Let me tell you what a community college is. First off, it is a junior college - two years. Usually it is a public college, financed by the municipality or the state or both. Usually it is co-educational. Usually it is only for commuting students - no dormitories. It serves a wide variety of students; indeed that is a part of its charm as well as a limitation. But there are essentially two groups of students: those who plan to transfer as juniors to four-year institutions and those who plan to go to work in a variety of occupations after just two years of college.

It is this multi-purposeness which accounts in large measure for the community college's surging popularity. Typically a community college has a transfer or liberal arts program which contains the same balance among the social sciences, the sciences, and the humanities that one would find in the first two years of a liberal arts college or university. It also has a variety of specialized programs, often called occupational, or technical, or terminal programs. These occupational programs, in addition to offering a core of compulsory liberal arts courses, include courses to prepare students to go to work in local businesses or industries. Pittsfield's largest employer is the General Electric Company, so Berkshire Community College numbers among its occupational programs one in electrical technology. Obviously, the more of these occupational programs the community college can offer, the more opportunity there is for each qualified high school graduate to find the one which suits his particular aptitudes and aspirations. Some colleges have up to twenty of these occupational programs in fields such as dental technology, nursing, banking, data processing, or petroleum tech- nology.

Another reason community colleges are burgeoning is that they're inexpensive. The first two years of college are cheaper to operate than the last two because larger lecture classes are suitable for many introductory courses (psychology, for example) and because less specialized equipment is required. A non-residential college costs only about half as much per student to build and to run as a dormitory college. The cost to students to attend a community college is a fraction of the cost of a residential college. Many community colleges are tuition free. At Berkshire and at the other five Massachusetts community colleges the tuition is $2OO a year and the total college cost for a student living at home is often under $400 a year. This economy makes all the difference to many students from large families or from families of limited means - it often means they attend college when they otherwise could not even consider doing so.

The community college is easier to get into, too. It may have an "open door" for any high school graduate. It is sometimes described as a uniquely American or democratic institution which recognizes the importance of the "average" person's having the opportunity to go beyond high school. The description is justified, I think. At Berkshire we don't have an "open door," but we do admit any high school graduate who looks to us to be a reasonably good bet to do the job in college. I say to our freshmen each year, "This is a relatively easy institution to get into, but it is not an easy institution to stay in." We wash them out pretty quickly if it turns out we guessed wrong at admission - about one-third flunk or quit the first year - but at least they've had the chance, and that's important.

WHAT about the quality of education offered in a community college? The fact that our attrition at Berkshire is high indicates we're not soft. But a community college has definite handicaps as it strives to keep the right kind of "institutional press" on its students. In the first place, we don't have the students for as long as we could wish. They are gone at the close of each day and they are gone after two years. They don't have the benefit of more mature upperclass- men to set a tone for them in the in- formal, out-of-class education which a residential institution offers. These shortcomings are very real. Cardinal Newman in The Idea of a University said that residence with one's fellow students is more important than professors or examinations for "training, moulding, enlarging the mind."

The community colleges have other shortcomings. Our students tend to come from the same socio-economic group as well as from the same geographic area, so some of the usual college stimulation of rubbing up against "strange" people is lacking. Nor do they get another kind of stimulation often associated with going to college, that of going away from home, of being "on their own." And, of course, two years of college is not really enough of college for most able youngsters, but that is all most of our occupational students get. (Woodrow Wilson is supposed to have said, "Anyone who thinks two years of college is enough has never seen a sophomore. The sap has begun to rise but it has not yet reached the brain.")

Also, the fact that community colleges are not selective in admissions means that there are students in the colleges who are not as well prepared to do college-level work as would be the case in most four-year institutions. There is a greater disparity in the aptitudes of the students and in the amount of information they have than one usually finds in a college. Some students who come to us are very bright and the community college must not hold them back while attending to the problems of their slower classmates. The problem is akin to that faced by public high schools and we use some of the same devices they do to solve it: homogeneous grouping in classes (but with a common grading standard), honors programs, developmental reading programs, special attention to the very quick student and the slower but especially persevering one. But obviously the 130-IQ student who comes to Berkshire (and each entering class has several) is going to find fewer intellectually challenging classmates than would be the case at Dartmouth or Smith.

ON the plus side of community colleges the very least that must be said is: Better to attend a community college for two years than not to have any college experience at all. And I think more than this can be said.

In the first place, community college teachers concentrate on their work in the classrooms and on counseling with students. They are not required to "publish or perish." The strongest teachers we can find are given the introductory courses where sparks of interest are most likely to be generated in students. Indeed, we often are able to attract first- class teachers who are interested in just this kind of situation. Many of our best teachers are non-Ph.D.'s who were blocked from promotion in the four-year institutions because they wished to concentrate on teaching rather than scholarship. They are pleased to find a college teaching assignment which does not demand that they continue to divide their energies between teaching and working at the frontiers of knowledge in their disciplines. This is not, of course, to derogate the dual-purpose role of the university and its faculty of teacher-scholars. Nor is it to say that we discourage scholarship on the part of our faculties; we want them to "keep up" in their fields and there is no better way to do this than by research. It is simply to say that our special emphasis is on teaching and not on scholarship and that this special emphasis adds a dimension of strength to the teaching that is done in the introductory courses in community colleges.

Many of the community colleges are small. Berkshire has 350 full-time day students in this its fourth year of operation and we won't go above 1000 for several years. This means we are quickly able to single out for extra attention the really able student or the one with special problems. Our being small means that many students are able to take on leadership functions they might otherwise not have. Extracurricular activities do play a part in community college education, though there is relatively more emphasis on the curricular work and perhaps less danger of a marginal student's being dazzled by the appeal of a variety of subsidized activities to the detriment of his studies.

For many students, attending the first two years of college while living at home is just right. For one reason or another, seventeen is not the right age for everyone to try his wings away from home. I recall the late Dr. Alan Gregg of the Rockefeller Foundation chiding educators for our pride in the slow-maturing nature of humans and our paradoxical insistence that maturity be assumed at the arbitrary cut-off age of seventeen or eighteen. The so-called "late bloomer often finds the community college the best garden. At Berkshire we have helped a number of students who left home to go to a residential college, found it a bewildering or overwhelming experience, especially at a large university, and as a result quickly flunked out. They have come to us, done well, and returned more confidently to the university as juniors. Some community college people refer to this as our "salvage function" and that strikes me as an accurate, if inelegant, phrase. In some cases the younger siblings of these "salvaged" students are coming to Berkshire in the first instance, as freshmen.

The lack of juniors and seniors to set a tone - a lack which has always struck me as a very real one in residential junior colleges, especially those which are geographically isolated - is in some measure offset in community colleges by the liberal sprinkling of more mature people in our classrooms. We have a number of housewives, for example, women in their twenties and thirties who come in to take one or two courses during the day while their husbands are at work and their children are in school. They lend a serious and purposeful tone. So do the older married veterans who find us the most feasible college to attend. These mature people, many of whom were caught in the "tender trap" and found themselves with families before they realized what they had missed in education, are almost wistfully grateful for the chance to pick up their lost opportunity. Their zest and energy in taking advantage of the opportunity make them a delight for their teachers and catalysts for their classmates.

THIS perhaps brings us to the "community" nature of the community college. Our colleges are assumed to be the opposite of the "ivory tower" institutions. One of our missions is to serve the community, to be the educational and cultural focal points in our regions. Hence the name "community college." We have adult education programs, lecture series, musical programs and plays, short non-credit courses for special groups to upgrade themselves, and a variety of other educational activities for which there is a need in our communi- ties. While these same functions are performed by lots of other colleges and universities, they are perhaps more central to the purposes of the community college. Last year Berkshire served over 1000 students in the day, evening, and summer programs; we held lectures by Norman Rockwell, Alistair Cooke, and C. Northcote Parkinson; we served as the "home" for a local symphony orchestra; we ran a series of seminars for business men in the area. But with all that we don't feel we are yet having nearly the impact on our community that many community colleges have on theirs.

One of the exciting things about this community college business is that many communities are having colleges established for the first time. Most of these communities are taking the colleges to their hearts as they would no other kind of institution. They sense what a college can mean to them, much as the upper Connecticut Valley communities did when they vied for Eleazar Wheelock's attention as he made plans for starting his college two centuries ago. And what has Dartmouth College meant to the upper Connecticut Valley? Visit the Hopkins creative arts center any weekend and you'll see. (We have a complex of two rooms at Berkshire devoted to some aspects of the creative arts; our Fine Arts man calls it "Son of Hopkins Center"!)

So municipalities and states are building flossy new campuses for their community colleges. They are planning to expand them to meet the crush of high school graduates during the next few years. That crush is enormous and it is almost on us. For example, the number of high school graduates here in Berkshire County jumps 40% in just two years between last June's class and the class finishing in 1965. Figures for New York and many other states are compa- rable. As for the community college's role in handling this avalanche of students, by 1970 three out of four high school graduates in the nation who go on to higher education will enroll in two-year institutions, according to a study by the Prudential Insurance Company.

The community colleges, in turn, must do their best to be sure that coping with this quantity doesn't preclude quality education. This brings us back to the key question of how good these colleges are and will be. They are, of course, like any class of colleges, uneven. If you want to see how bad they can be, read TheOpen Door College by Burton R. Clark, which describes a new two-year college and its difficulty in establishing itself as a genuine collegiate institution.

But community colleges can be fine colleges, too. One measure of their quality is how well their graduates do in good four-year institutions when they Transfer as juniors. The record is impressive. A number of studies have shown that community college student transfers do as well or better than their classmates who matriculated in the four-year institutions in the first place. At Berkshire we were pleased (no, overjoyed!) to find that our first group of 111 graduates who went on to forty different four-year institutions with credit for their community college work (there has been surprisingly little problem in transferring credits) achieved on an average a 2.45 cumulative index on a 4.0 = straight "A" scale their first semester. This would be slightly better than their junior-year classmates.

How do the four-year institutions feel about the new community colleges? The state universities are by and large delighted to delegate the task of screening large numbers of freshmen and sophomores so that they can concentrate most of their energies on upper-division and graduate education. On the campuses of the University of California, for example, there are twice as many juniors and seniors as freshmen and sophomores. In Florida, new state universities are not admitting any freshmen or sophomores. Their students will all be community college transfers. In the Northeast, too, the four-year institutions are beginning to demonstrate an awareness of the community colleges. Dean of Admissions Eugene S. Wilson of Amherst College announced a short time ago that Amherst would actively seek applications from fifty transfers from junior and community colleges each year. Students from Berkshire have already transferred to Middlebury, Brandeis, Simmons, and several other "prestige" institutions. (After all, it was a shorter time ago than most of us keep in mind - just before World War II, as a matter of fact - that the "prestige" institutions were admitting many "average" students who now find most doors closed to them except those of the community college.)

It may well be, though, that over the long pull the community colleges' greatest contribution will come not in this transfer function but in helping to meet what Walter Lippmann has called the most pressing unfinished business facing our nation: "the gigantic work of adjusting our way of life to the scientific revolution of this age and to the stupendous growth of the population." By providing the communities across the nation with flexible post-high school educational institutions committed to offering some form of higher education to everyone willing to prepare for it, the community college may be a decisive factor in our adjustment to this scientific revolution. Soon a high school education will be insufficient as preparation for any but the most menial job. Even now there are not enough menial jobs for those prepared to do no others. At the same time, our society's` need for technicians or pre-pro- fessionals is greater even than our need for professionally trained people. The occupational programs of the community colleges may prove the best way to meet this challenge, both by educating young people coming out of high schools and by retraining their elders to adjust to automation and new ways of doing the nation's work.

So far, the community colleges, including Berkshire, have talked much better than they have performed in occupational education. We have not really yet begun to educate technicians in anything like the numbers needed. We'd better start soon, and I think we will. The trick will be for our community colleges to remain flexible enough and zestful enough and imaginative enough to meet the special new educational needs of the United States which community colleges appear uniquely well-suited to handle. We must be in fact, as well as in name, "a new college for a new society."

For many of us at Berkshire Community College, and at other community colleges I know, the challenges we face are the most exciting in higher education.

Some psychology students at the Berkshire Community College in Pittsfield, Mass.

The community college also enrolls foreign students. Masri Maris from Indonesia(second from the left) is shown in this world affairs discussion group at Berkshire.

THE AUTHOR: Mr. O'Connell's activities before becoming President of Berkshire Community College, a post he has held since 1960, included two years as executive assistant to President Dickey at Dartmouth, 1955 to 1957. Holder of the master's degree in public administration from the Maxwell School at Syracuse University, he was administrative assistant to the Managing Director and then to the Director of Commerce in Philadelphia before returning to Dartmouth in 1955. He left the College to become Deputy Budget Director of New York State and in 1959 became public administration adviser to Ecuador's government for the United Nations. His work as executive consultant to the Massachusetts Board of Regional Community Colleges led to his being named head of Berkshire, the first community college in the state. Mr. O'Connell, chosen as one of the four outstanding young men of Massachusetts in 1962, was winner of the Barrett Cup in his senior year at Dartmouth. He was president of his class, Green Key, and the Undergraduate Council.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

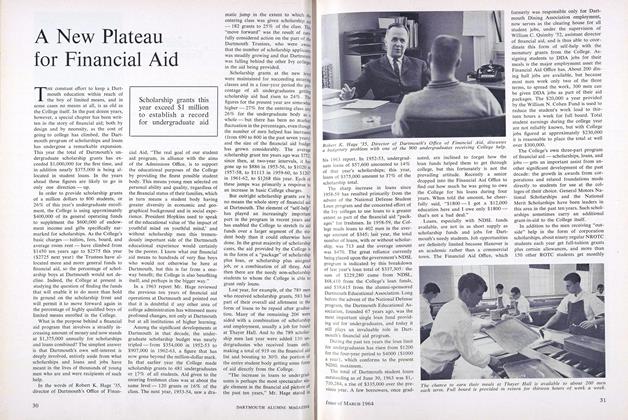

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

March 1964 -

Feature

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

March 1964 -

Article

ArticleA graduate of 1804 who stood up for an American Culture

March 1964 By BEN HARRIS McCLARY -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

March 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1964 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER

THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRUSSELL RICKFORD

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureNever Say Die or Adversity Foiled the Story of 100 Years of Rowing

April 1957 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

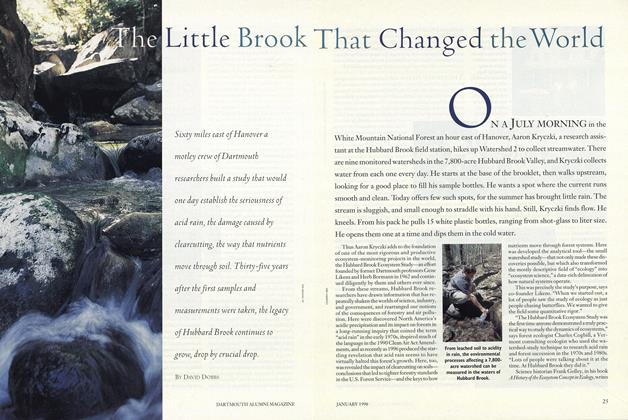

Cover StoryThe Little Brook That Changed the World

JANUARY 1998 By David Dobbs -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

November 1974 By V.F.Z. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Translation

DECEMBER • 1985 By WILLIAM C. SCOTT -

Feature

FeatureThree Civil War Letters

May 1958 By WILLIAM D. HARTLEY '58