George Champion '26, Chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank, is also close to being the No. 1 U. S. banker, both in the size of the institution he heads and in his personal contributions to its special style of operation

SENIOR EDITOR, FORBES MAGAZINE

THERE is no question about George Champion's primacy among Dartmouth bankers, despite the challenge of men like Chairman Lloyd D. Brace '25 of Boston's redoubtable First National. For Champion, as chairman of Chase Manhattan, heads New York's biggest commercial bank, with year-end deposits of nearly $11 billion and assets of over $12 billion.

Indeed, Chase Manhattan might be regarded the top U.S. commercial bank, depending on how one classes that Western giant officially named Bank of America National Trust & Savings Association. For its deposits of over $13 billion and assets of over $14 billion were acquired in a state lacking the big mutual savings banks with which Chase Manhattan must share one part of its business. And Bank of America blankets California with its 850-odd branches, while Chase Manhattan has been allowed to open just nine branches in New York outside the city's five boroughs, where it has 115.

George Champion's story has a slightly unreal tintype cast, until one reflects that the tale of the widow's-son-who-rose-to-be-bank-president became a tintype only because of how often it really happened. Born in 1904 in central Illinois, he grew up on a farm outside the little Illinois college town of Normal near Bloomington (teacher-training colleges were then called "normal schools"). When he was 11 he lost his father, and soon moved with his mother and two sisters to San Diego. His public high school days there were punctuated by brief periods of manual labor in the wonderful unspoiled country around San Diego, which he remembers fondly as "the greatest place in the world for a young fellow to grow up in." After graduating from high school he stayed out for a year, working part-time and taking a few courses in a local college, before entering Dartmouth in the Class of 1926 - the first, he recalls, to be chosen on a regional basis.

But there were not enough kindred spirits to keep him from being, he admits, "homesick as the devil" when he first hit Hanover — which is strong language for a man whose speech runs to farm-country epithets like "dag-gone." However, he recovered quickly as do most pea-green freshmen, and went on to become something of a campus leader. He joined Psi U and (later) Casque & Gauntlet; eased the financial pinch by waiting on tables at the Wheelock Club, selling banners door-to-door ("We put on our 1926 numeral sweaters and went to work on the freshmen"), and helping set up special vacation trains to distant points like Chicago; and formed his lifelong attachment to men like President Emeritus Hopkins, whom he calls "one of the greatest influences in my life."

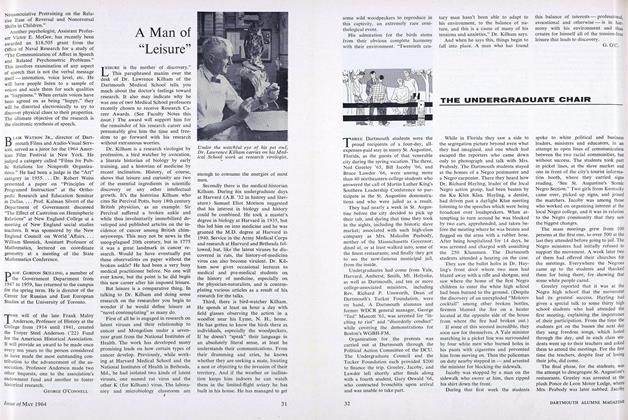

Champion, at 60 still a rangy and powerfully built man, played right guard on the famous undefeated football team of 1925. But his most vivid football recollection is, interestingly, a moral one. He describes almost with awe how Swede Oberlander, great halfback of the 1925 team, refused on principle offers of thousands of dollars to play single professional games, offers that Red Grange and others accepted. And Oberlander, observes Champion in true bankerly fashion, was doubtless in debt at the time and had long years of medical education just ahead.

Perhaps the most noteworthy thing about Champion's academic career was how a man who majored in political science and history, and became a banker, happened to get a B.S. degree. In his junior year he and his roommate, Chuck Webster '26, took a Greek course together to satisfy a classical language requirement. They pulled A's on the midyear exam ("much to Professor Nemiah's surprise") with the aid of a two-day pre-exam study routine consisting of 45 minutes' study followed by 15 minutes' penny-ante poker. But that spring Champion did not mount such an effort, and flunked the course. The makeup physics course he took his senior year tipped the balance to a B.S. degree.

The young Bachelor of Science had no preconceived notion of becoming a banker when he invaded New York after graduation. But an employment agent referred him to an opening for a mail teller at the National Bank of Commerce. "They were hard drivers," says Champion, recalling his 8:00 A.M.-6:30 P.M. hours with a half-hour off for lunch. But he regarded the Bank of Commerce, which had a blue-ribbon clientele, as being a better education than a business school. And his official duties did not keep him in 1928 from marrying Eleanor Stevens, whom he had met at Smith during both their senior years.

Champion came to Chase via merger, moving in 1929 to the Equitable Trust which the next year merged with Chase. And in 1931 he drew the assignment that was a route to the top as well as a means of major contribution. New Orleans' Canal Bank, in which Chase had a stake, was in trouble; and Champion was sent as the junior member of a two-man rescue team.

The job had its dramatic moments - as when Huey Long suggested appointing a friend vice president. ("Senator," said Champion, "you run the state and we'll run the bank.") But more important, Champion learned about the ties between Chase and the smaller banks in the hinterland. "We'd loan on a mule and a cart," he says. "In 1931 or 1932 we had some $2OO million loaned out. We kept some of the country banks from folding - and they've never forgotten it."

Later, therefore, as top Chase representative in the southeast and then as head of the bank's United States department, Champion nurtured with special care the relationships with out-of-town "correspondent" banks, whose business is one large factor in keeping Chase Manhattan the biggest New York bank. And the domestic example played a part in forming Chase Manhattan's overseas preference for working with foreign correspondent banks in most situations, rather than setting up its own branches.

Another major Champion contribution was in helping to bring the bank's personnel policies in line with the new currents in banking. The story of the big New York banks in the last three decades is the story of the trend from "wholesale" to "retail" banking - that is, from serving a handful of corporations and moneyed individuals to handling the checking accounts, small loans, and other banking business of the millions. The culmination of the change for the staid, wholesale Chase was its 1955 merger with Bank of the Manhattan Co., with its 66 branches, to form Chase Manhattan. But long before then George Champion had spent a full year investigating and refurbishing Chase's personnel practices to fit them to the new age.

Champion's patient nurturing of cooperative relationships with other banks, or his willingness to hear countless employee gripes and suggestions, does not imply that he is any less a conservative. For example, he is probably more conservative in general outlook than Chase Manhattan President David Rockefeller, whose background includes a stint as welfare secretary to New York's great reform mayor of the 19305, Fiorello La-Guardia. Champion is more than moderately dubious about the wisdom of the U.S. foreign aid program as a whole, and extremely so about its present functioning. He can grow wrathful in a moment over "exorbitant" union demands, "mushrooming" veterans aid, "bureaucratic pressures" from Washington. And he once complained vigorously to President Dickey about the College's use of an economics textbook that he thought an egregious misrepresentation of the American system.

But the important point is that his personal predilections, no matter how strong, do not inhibit the operation of his healthy sense of realism, which finds the most practical reasons for necessary reforms. Thus he completely agreed, for sound competitive and operating considerations, with the need for remaking the bank's personnel policies. And he is keenly aware of how much the executive depends on the cooperation of the people working for him. For a hostile staff, he remarks with typical pungency, "can cut your throat with a dull knife."

Such men typically feel a strong urge to take part in charitable and other worthy-purpose organizations; and Champion's list is far too long for recital. However, he has been president of the Protestant Council of the City of New York, and he is currently (among other affiliations) treasurer of the United Negro College Fund and a trustee-at-large of the Independent College Funds of America. But the one that makes his eyes sparkle most these days is Youth Development, Inc., a street-level effort in East Harlem to straighten out a group of predelinquent teen-agers.

Its appeal for Champion seems to lie in the tangible nature of the undertaking, as opposed to some larger, perhaps more fruitful, but certainly more remote administrative scheme. And the same would seem to apply to his connections with Hanover, which tend toward the personal rather than the organizational side. Thus, he still supplies cigars to his favorite teacher, former zoology department chairman Doc Griggs. In fact, he was delighted not long ago to hear that Doc Griggs referred to this largess from Psi U Champion in a remark to President Emeritus Hopkins, himself a Deke. Complained Griggs, "The Psi U's keep me in cigars, but what are the Dekes doing for me?"

Lawrence C. Marshall '25 (left), Chase Manhattan's Vice Chairman, conferringwith Mr. Champion on bank, not Dartmouth, matters. They magnanimously alloweda Harvard chap named David Rockefeller to become president of the bank.

Champion, who played right guard on the1925 championship team, shown in frontof the C & G House in his senior year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUNITED EUROPE, THE GENERAL AND THE BOMB

May 1964 By HENRY W. EHRMANN, -

Feature

FeatureA New Strategy of Liberal Learning

May 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

May 1964 By BARRY C. SULLIVAN, GILBERT BALKAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

May 1964 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1964 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, JOHN s. MAYER

Features

-

Cover Story

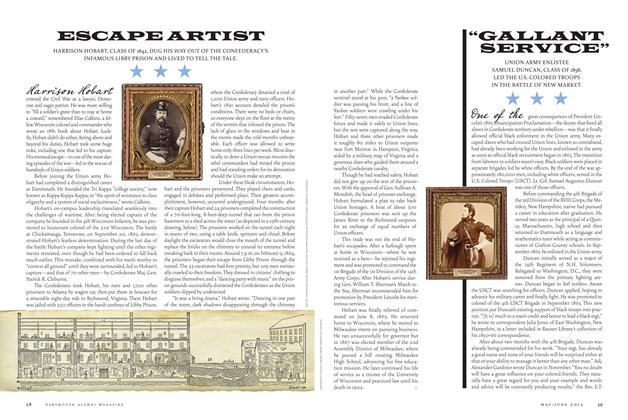

Cover Story"GALLANT SERVICE"

May/June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureA Panathenaic Prize Amphora

JUNE 1959 By DIETRICH VON BOTHMER -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mt. Everest

MAY 1983 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1958 By LAURIS G. TREADWAY '08 -

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureStudent Workshop

MAY 1957 By VIRGIL POLING