PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

THERE is no need to repeat here the often-told story of how laboriously and slowly the various so-called European Communities have been built. For our discussion of the present crisis in Western Europe and of the difficulties that have arisen in our relations with Western Europe only a few salient points about past developments are of importance. There are first of all the striking successes which the six countries of the Common Market have scored. In standard of living, rate of economic growth, modernization of the economy and of the society as a whole — in most of these terms the nations of "Little Europe" are now far ahead of the rest of Europe and even of the United States. While it is not always easy to assign a single cause to each factor, there can be no doubt that the treaties by which the European Community was built have proved to be an important ferment for change. All this was brought about without any commitment to a definite economic or social philosophy. It was done rather through a pragmatic mixture of planning and lais-sez-faire, of public and private enterprise and investments.

Among the political consequences the most important was the Franco-German reconcilation. Institutionalized first by the Coal and Steel Community, it has been solidified ever since. It is far less easy to describe what the growth of the Communities has done to traditional inter-state relations. Both the wishful thinkers, who discover a nascent federalism in everything they see, and the traditionalists, who are blind to the transformations that have actually occurred, have frequently confused the issues.

The Treaty of Rome which created the Common Market and laid the foundations of a customs union is actually even less federalistic in character than the earlier Coal and Steel Community. In all of the existing Communities the nation state is still predominant and can, with very few exceptions, impose its decisions on the Community organs. The European Assembly, which has been likened to a federal legislature, has only an advisory role and is indirectly elected. The executive organ with real powers is the Council of Ministers in which the six governments are represented and which, so far, reaches its decisions by unanimous vote. Only after 1965, when a new phase will be inaugurated, can certain important questions be decided by a qualified majority vote. After that time even one of the larger nations, such as France or Germany, could be outvoted - a perspective which is distinctly unpleasant to some European leaders. One can therefore speak of a certain escalation of Community procedures, and this is all the more significant since the Common Market has traveled through its various stages with greater speed than originally anticipated.

Even now Community decisions, however slow and painful their elaboration, have already done much to modify relations between nations and have affected deeply the conditions of individuals and of groups. The nation states may still hold the veto over decisions, but they no longer have the monopoly of action. The "community spirit" has nothing mystical about it. It is made into a living reality by the European civil servants working in the various Communities, by the members of different European movements, by some of the delegates to the European Assembly. What develops here might defy exact legal definition; it is nevertheless a dynamic process out of which there emerges, almost behind the backs of the national governments, an embryonic federal executive and administration.

For the so-called functionalist school this is all that is needed. They believe that political unity will emerge spontaneously and painlessly out of the existing processes of economic collaboration. Together with many others I do not believe that a true political federation has ever been formed in such a "clandestine" fashion. Our own history attests to that. In today's Europe whenever an emergency has arisen, be it the coal crisis or a dispute over agricultural prices and subsidies, the national governments had the last word and there was no federal authority to impose the interest of the entire European Community on a recalcitrant government. The newspaper headlines attest to the fact that in the all-important matters of foreign and defense policies the nation states determine the course of action. We have therefore to conclude that if and when the day for a truly United Europe comes, a new treaty instituting "a more perfect union" must be concluded.

WE will come back to speculations about the future. Let us first look at the relationship between the European Community as it exists today and the broader Atlantic Community. Relations between the incipient European union and the Atlantic alliance were obviously easiest as long as the power of the United States was clearly predominant because of the economic distress of Europe and because of our atomic monopoly. Nonetheless it was clear from the very beginning that a potentially strong and united Western Europe might one day take a more critical view of the idea of an Atlantic alliance. If one hoped to see emerge a true Europeanism, something like a European nationalism, then it was possible and even probable that interests between that new union and the Atlantic Community might not always be identical. The United States recognized from the very beginning that once the Common Market became a going, concern, it might create difficulties for our foreign trade. But we were convinced that economic disadvantages would be outweighed by the political advantages which we and the entire free world would derive from a better organized and hence stronger European partner.

Now that Europe has recovered and found a modicum of unity, it is less dependent on the United States than it has been for half a century. In answer to this new situation we have developed what is sometimes called the dumb-bell concept, with Europe and the United States being two spheres of equal weight on a rod. The best expression of this concept was given by President Kennedy in his Independence Day address at Philadelphia in 1962, when he stated that the United States was ready for a declaration of interdependence. "We are," he said, "prepared to discuss with a united Europe the ways and means of forming a concrete partnership, a mutually beneficial partnership, between the new union now emerging in Europe and the old American union founded here a century and three quarters ago." This was the granddesign of the Kennedy administration. By speaking about interdependence it definitely rejected the idea of an independent third force in Europe. It might have assumed somewhat too readily that the partnership would always be mutually beneficial, that a community of interests in such far-flung fields as agricultural surpluses and tariffs could always easily be established. But such noble words were followed by deeds; legislation initiating the so-called Kennedy Round, the Trade Expansion Act, was a direct answer to the situation created by the European Common Market.

In his speech Kennedy referred to the new union in Europe without mentioning Great Britain as an outside force. Indeed, that new union was to include Great Britain because at the time the President spoke it seemed that Great Britain was finally giving up its long resistance to joining the European Community. Britain's record toward a united Europe had been far from brilliant. All postwar governments in England were insensitive to the significance of the Community experiment. All of them insisted ferociously on British sovereignty; the Conservatives distrusted what they called European constitution-mongering; the Laborites disliked what to them were Catholic reactionaries in the governments of the Six. Britain made constant efforts to dilute the cement binding the Communities; it wished to keep the alleged advantages of Commonweath ties and still get special advantages in Europe. This finally changed. By 1960 it had become evident how brilliantly the Europe of the Six had succeeded while Britain tottered once more on the brink of economic disaster. Finally Prime Minister Macmillan made application for admission to the Common Market, and proudly called this the biggest and most forward-looking decision in British peacetime history. The difficulties to be negotiated were considerable, but they were constantly being narrowed and when Kennedy spoke it seemed quite clear that Britain would soon become a full-fledged partner of the European union.

And then the General said No.

His blackballing of Great Britain was, like all blackballing, a crude and cruel violation of the democratic majority principle. When he closed the door to the British, General de Gaulle also spoke out explicitly against the concept of interdependence and against any further strengthening of the Communities by federal ties. I would not agree with the London Economist which called De Gaulle's position "demented." That extraordinary man is extremely rational in all he does. I am inclined to agree with the title of a widely discussed article in TheReporter Magazine entitled "Cursing De Gaulle Is Not a Policy." But what we must do is first explain De Gaulle's policies and then show their likely consequences for Europe and possibly for the peace of the world.

THE exclusion of Great Britain by De Gaulle is entirely in line with the General's vision of the present-day world. He believes that both the Soviet Union and the United States will soon be completely disinterested in Europe, because we will have difficulties in our Latin American backyard just as the Russians will be concerned about China. Moreover, to the General political ideologies matter little. The opposition, between democracy and communism is to him but a sham fight. What counts are national interests, and those interests will lead the two super-powers to withdraw from the Continent. At that time, he thinks all of Europe, not just Western Europe, should and could become an independent power bloc. When he envisages a "Europe for the Europeans," he might believe that he is merely throwing back at us the ideas of Washington's Farewell Address and of the Monroe Doctrine. But does he consider how anachronistic such concepts have become in our day?

The independence he seeks, the General argues further, would be impossible if Great Britain were to represent what he calls the "Anglo-Saxons" in the councils of Europe. To explain General de Gaulle's animosity against Americans and British alike, much is made of his unfortunate wartime experiences when as the leader of Free-France-in-Exile he had reasons to feel slighted. I actually do not believe that the General is that small a man. It might well be that temperamentally the introvert Jansenist in De Gaulle is unsympathetic to the British and our world outlook. But most important is the fundamentally different way in which he and we judge the present-day international situation. The somewhat pointless negotiations between Kennedy and Macmillan at Nassau in December 1962 only confirmed De Gaulle's idea that Great Britain still wanted special ties with the United States and was therefore ineligible for a truly "independent" Europe. This explains why De Gaulle has spoken with scorn about "a colossal Atlantic Community under American dependence and leadership which would soon completely swallow up the European Community." With such words the French President opposed the very idea of Kennedy's grand design.

Here one might draw a parallel between De Gaulle and Bismarck. About a century ago Bismarck excluded Austria from German unity so that Prussia might dominate the future Reich. Did the General fear that Britain would compete with France for the leadership of a united Europe, and especially that the presence of Great Britain within the European Community would open for Germany an alternative to her close collaboration with France?

But why did De Gaulle slam the door not only on England but also on European federalism and other forms of closer integration of the Six? This appears illogical. For if De Gaulle wishes a strong if narrower Europe, able to play the role of a third force independent of the Atlantic powers, then he ought to prefer an integrated union to a loose confederation, and should wish for an integrated European military force possibly in possession of atomic weapons. His failure to do so sheds serious doubt on De Gaulle's real intentions.

WHAT are his arguments against further European integration? He treats with contempt what he calls the technocracies in Brussels and Luxembourg where the European Communities are administered. In his opinion they are removed from popular will and are possibly a danger to the correct defense of national interests. It is somewhat strange that such reproaches should come from the leader of the Fifth Republic which is closer to a technocratic regime than many other modern democracies. It is correct and for a time unavoidable that, given the complicated supra- and international network, an international bureaucracy has indeed a major share in preparing Community decisions. In order to give a democratic underpinning to executive decisions, many, including the German Government, have proposed that the European Assembly should be chosen by direct popular elections. Then the Assembly should be given such powers as the right to introduce legislation, to control the budgets and to censure, if need be, the members of the European executives. Of course, this would be a step towards a truer form of federalism. But here De Gaulle's refusal is once more categorical. His arguments are antithetical to the very processes of the give and take of democratic decision-making. He argues that since there is no European nation, only the agents of the separate popular wills can make legitimate decisions, only national governments can recognize the common good, which like Rousseau's general will exists somewhere a priori.

There is, of course, no doubt as to who is the judge of the common good in the French Republic. It is De Gaulle himself. French cartoonists have for a long time portrayed De Gaulle as a latter-day Louis XIV who said arrogantly L'Etat c'est moi! As time goes on De Gaulle seems also to be saying L'Europec'est moi! to all those who criticize his concept of a "Europe of fatherlands." He has indeed specifically stated that any system "leading to the transfer of sovereignty to international bodies would be incompatible with the rights and duties of the French Republic." Hence, De Gaulle, who proclaims that he wants a cohesive, autonomous, and independent Europe, refuses to this Europe the institutions which might possibly insure such a status.

Again we have to ask, "Why?" There can be no doubt that an intransigent nationalism is a central motor for De Gaulle's actions. His memoirs open with a rather beautiful and significant passage: "All my life I have thought of France in a certain way. ...Instinctively I have the feeling that Providence has created her either for complete successes or for exemplary misfortunes." And he then explains that he prefers exemplary misfortunes to mediocrity: "France can-not be France without greatness."

Now this is not just an old-fashioned eighteenth century concept of national grandeur. If it were that, it would be so quixotic that it would hardly be dangerous. But De Gaulle is not a museum piece. His idea of national greatness might possibly have an altogether modern and nefarious meaning. What he aims at is a streamlined continental nationalism guided by the oldest and most glorious of European countries. A European confederation under the hegemony of one power, namely France, would then be large and strong enough to play an active and possibly turbulent role in world affairs. This explains why one day France offers, without any previous consultation, its own solution for a settlement in Vietnam, why the next it restores a fallen African leader to his position, why the General exalts the solidarity of France with the Latin-American republics.

All this is done in the name of Real-politic, out of a conviction that also in our time nothing matters but the interests of the nation state. It is quite true that European opinion polls reveal at best a strongly felt but only vaguely thought-out sympathy for a United Europe. There is little concrete evidence of a widespread identification with the idea of a European federation. Hence I do not wish to convey the impression that De Gaulle by his deeds and words destroyed an existing impetuous will to build such a federation. What existed before 1962 were indeed incipient and uncertain feelings whose intensity varied from one country to the next, from one generation to the other, and were probably always stronger among the elites than among the masses. What was needed was a development of these feelings which were steadily strengthened by the success of the existing Communities.

Such a development has been interrupted by the willful action of the French President. That politics is the art of the possible can hardly be denied. Also President Kennedy has said that we must deal with the world as-it is, not as it might have been had the history of the last eighteen years been different. But such realism does not belie the faith of another Frenchman, the poet Victor Hugo, who spoke of the power of an idea whose time has come. A more perfect European union was no longer one of those Utopian dreams with which history is strewn, but an idea whose time had come. And against this idea in the making De Gaulle has set himself. What are the chances that he might succeed and what might be the possible consequences?

So far I have left untouched problems of military security in Europe or in NATO. This is a large topic by itself, and I do not claim any particular competence to deal with a problem that obviously stumps the experts. Let me merely make a few political observations. Beyond all technicalities the goal is to make the United States nuclear deterrent believable for foe and ally alike, and yet insure that the destruction wrought by a possible armed escalation is not out of proportion with the interests involved in a particular military situation. This is difficult of solution, especially since the United States no longer has an atomic monopoly even in Europe. It is the question of how many fingers should be on the atomic trigger. One might also say it is a question of who shall die for what and in what circumstances. In 1939 there were Frenchmen who claimed that they did not want to die for Danzig. There are now Frenchmen who doubt whether we are willing to die for Hannover or even Berlin.

What matters, it seems to me, is to develop a solid strategic consensus among the NATO allies, reliable planning to decide under which conditions which weapons would be used. The control of missiles and warheads is secondary to the agreement on basic policy processes which determine peace and war as well as the forms of war. Certainly what I have said calls for better integrated and partly novel NATO practices. Whether it also calls for a transformation of the treaty into a military federation, as Professor Morgenthau has written, I am not prepared to determine. But we must keep in mind that the NATO Treaty is up for revision in 1969 and that De Gaulle has already declared that if he is still around at that time, he wants to try his hand at some modification of NATO. There is little doubt that what he has in mind will not lead to a stronger integration of the armed forces but rather will go in the opposite direction.

It is equally certain that national nuclear striking forces, be they French or others, can only complicate the task and deepen the fissures in the Atlantic alliance. Militarily, the small nuclear "emergency parachute" which the French are now developing corresponds to no plausible hypothetical military situation in Europe. Also De Gaulle knows, of course, that its deterrent effect is nil. He might consider this nuclear force useful to appease a restless officer corps which has never forgiven him the withdrawal from Algeria. But most important for De Gaulle is the nuclear striking force as a political weapon. Just as De Gaulle as a young officer insisted that France must have mechanized armored units in order to conduct an offensive foreign policy, so he is now convinced that France can-not have an active foreign policy without possessing the newest offensive weapon, even though only in a homeopathic dose.

WHAT then, in view of the present difficulties, is the political future of European unity? From the present vantage point I see two alternatives. The dark prospect can be sketched as follows. Serious dissensions might well develop within the Common Market over farming policies; they have been solved only provisionally under a blackmailing threat of De Gaulle, a blackmail which in this particular instance was salutary. Other and grave problems might arise this summer over the tariff issue between the Common Market and the United States. If such and similar difficulties increase from all sides, the existing Community framework might not be sufficiently strong to reconcile conflicting interests. It is then not inconceivable that the Communities would fly apart, the tariff walls go up, quotas and the blocking of currencies be reinstated. All this would, of course, be more threatening if the present prosperity and the high rate of employment in Europe were to decline, which is not impossible.

At the same time, nationalism might spread first in France and then across the Rhine. In France the political elites of the preceding republic were strongly committed to Europeanism, but these elites are now gravely compromised, which can only do harm to the idea of a united Europe. At present there is little resistance to that policy-making by thunderbolt which the General practices. If one observes the French scene closely, one feels that little by little the flattering idea that France is once more a great nation is kindling the patriotism of a people who previously had grown skeptical about grandiose nationalist schemes. Not so long ago the General exported this flattery personally to Germany when he told the German masses that came to greet him that they were a great nation. Many political leaders of the German Federal Republic believed this was the last thing a French nationalist should tell their people. There exists already in Germany, and right in Chancellor Erhard's own party, what is called a Gaullist faction. These men feel, like De Gaulle, that the days of American hegemony in Europe are over and that it should be replaced by a Europe dominated by France and Germany. And some of the Germans are even hoping that this would one day make German reunification possible.

Certainly the present Bonn government does not wish nuclear armaments for Germany. But is it conceivable that if now France and later possibly other European nations acquire their own nuclear deterrents, the Germans will forever renounce nuclear arms? But the

atomic rearmament of Germany is precisely what the Soviet Union and its satellites dread. Hence the danger which De Gaulle now believes eliminated could recur - the Soviet Bloc could be consolidated and feel threatened by the West. In such a case would not the French or another national atomic force either invite a preemptive attack or have to be used precipitately because of its own vulnerability? In such a situation, one might further ask, would a NATO deterrent be plausible if the alliance has gradually dissolved because all over the world American and French interests have clashed?

Although this might happen, it need not happen. I am fortunately far from being as definite about the split of the Western Alliance as the Kremlinologists are about the split between the Soviet Union and China. Of course, there are many parallels in the two situations. To a certain extent De Gaulle is our Mao. And there is even a relation of cause and effect. De Gaulle himself says he would not act the way he acts if in his opinion the Soviet Bloc was not irretrievably split.

BUT what would be the more optimistic prospect? The European Communities have undoubtedly shown resilience, even since De Gaulle's various No's. What has been achieved in Europe, it can be argued, cannot be destroyed by one man. There have been pauses in the movement towards European unity before, and the forward movement will again be resumed at some future moment. This will happen when French national interests call for it, either after it has become obvious to De Gaulle that his present policy leads to isolation, or when the interests of his country will be determined by somebody other than De Gaulle.

It can also be argued that the solidarity between the United States and Western Europe is more important than the particular forms it has assumed in the NATO Treaty, since that treaty was conceived in circumstances which have, of course, drastically changed in twenty years. A new arrangement of mutual commitments might be found, the interdependence about which Kennedy spoke might be institutionalized in different fashion. This implies, of course, that the United States will neither economically nor militarily retreat into isolation even though we realize that we are no longer either the guardian or the tutor of Europe.

In a recent article Professor Hoffmann of Harvard has brilliantly demonstrated that one might hear behind the clash of interests and ideologies in contemporary international relations something like a permanent dialogue between Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant. For Rousseau the only alternative to permanent war was the Utopia of isolated communities. Since in our day there is no salvation in such a Utopia, Rousseau leaves us with no way out of recurring wars. Kant, on the other hand, believed that past catastrophes and the actual converging of national interests would one day lead nations to harmony through interdependence. To him a federally organized league of states was the only way to that "eternal peace" to which he devoted an admirable essay.

Also in present-day Europe the existing Communities were born out of the dread of a dismal past and because of a new insight into the existence of shared interests. The organizations which have come into being and which have expanded since 1950 contain many of the elements of the league about which Kant wrote not long after the American Revolution. Whether they will become, before too long, a full-grown union, or at least an effective security community, waits upon the event. But if the darker prospect which I have described is to be avoided, European unity and the Atlantic Community must ultimately progress to higher forms of integration.

"Your universal key only seems to be able to take things apart."

"L' Europe? L'Europe c'est moi!"

PROFESSOR EHRMANN'S ARTICLE is a revised version of a lecture entitled "European Unity, Its Uses and Limits" that he gave in the Great Issues Course on March 2, 1964.

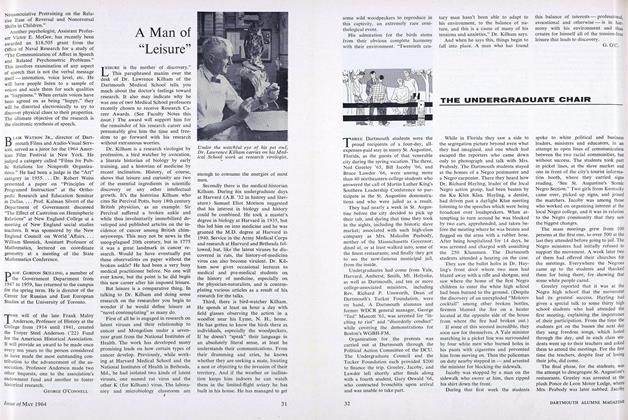

THE AUTHOR: Henry W. Ehrmann, chairman of the Department of Government, came to Dartmouth in the fall of 1961 after teaching political science at the University of Colorado for fourteen years. He gives a course in comparative political systems and also conducts a seminar in comparative government for majors. He was chairman of the faculty planning group that devised Dartmouth's new Comparative Studies Center. Professor Ehrmann was born in Germany and studied law at Berlin and Freiburg. He knows France particularly well, and was with the International Institute of Social History in Paris before coming to this country in 1940. He is the author of French Labor from PopularFront to Liberation (1947) and Organized Business inFrance (1958). He spent the summer of 1962 in France as a Fulbright Lecturer. Professor Ehrmann has edited books for UNESCO and the International Political Science Association, and recently he collaborated with Dr. James B. Conant on a Ford Foundation study of social-studies teaching in the Berlin school system.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

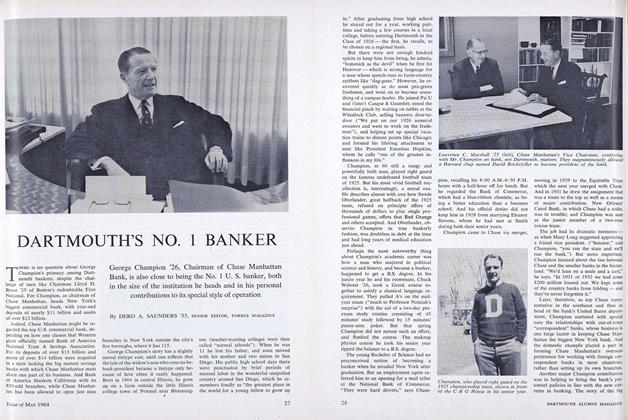

FeatureDARTMOUTH'S NO. 1 BANKER

May 1964 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35, -

Feature

FeatureA New Strategy of Liberal Learning

May 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

May 1964 By BARRY C. SULLIVAN, GILBERT BALKAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

May 1964 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1964 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, JOHN s. MAYER

Features

-

Feature

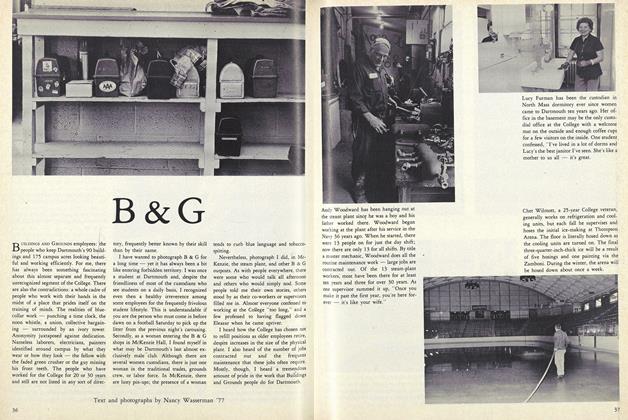

FeatureB & G

NOVEMBER 1981 -

Feature

FeatureFrom Dartmouth Comes the World's First Love Story

MARCH 1989 By David Birney '61 -

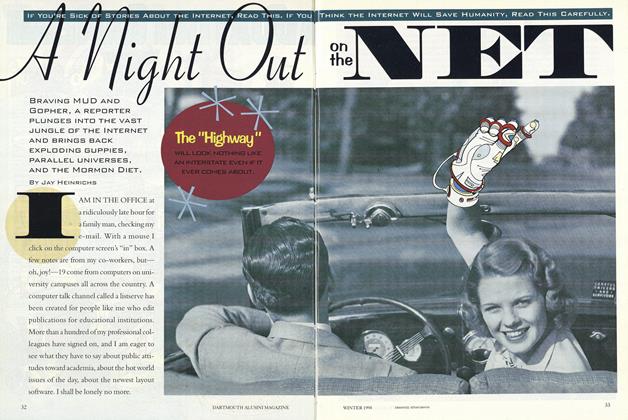

FEATURE

FEATUREDramatically Different

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2016 By HEATHER SALERNO -

Cover Story

Cover StoryProcrastinator’s Night Confessions of a Collegiate Insomniac

Winter 1993 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

COVER STORY

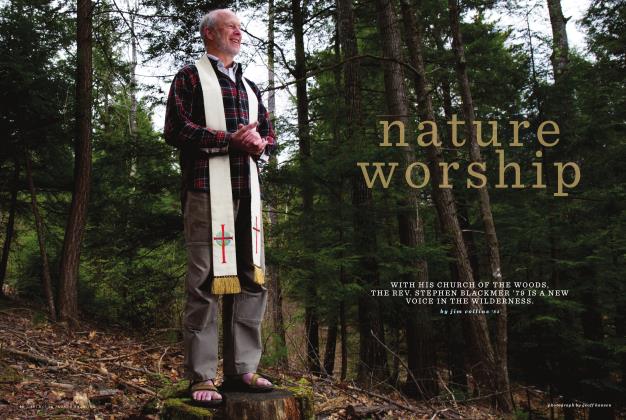

COVER STORYNature Worship

MAY | JUNE 2019 By jim collins ’84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Tasting

MARCH 1995 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38