PRESIDENT, THE CANADIAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

WHEN you look outside, beyond the confines of these three English-speaking Atlantic associates, the countries that retain a comparable basis are alarmingly few. They are pretty well confined to northern and to western Europe and to one or two of the older members of the Commonwealth. Throughout the vast remainder of the world you see either the lowering bulk of those who seek our overthrow, or a confused kaleidoscope of old states whose foundations are shaken by fitful tremors and new nations whose solidity has still to be established. And brooding over the whole scene is the tremendous new force of atomic energy, whose destructive powers must be held in leash if any of us are to survive, and whose peaceful uses will have an impact on economic and social patterns that will test our talents for flexibility as never before in history.

There is no question about our unity on basic objectives in the face of this situation. The elements are simple. We are resolved to contain, and where possible to curtail, the territory over which totalitarian communism has extended its domination; and we seek to advance by all practical means, not only the welfare and stability of the non-communist world, but equally the sense of common interests and the habits of practical cooperation that will make for an increasing unity based on a recognition of common aspirations and ideals.

In the first case, the main instrument of our security is of course the Atlantic alliance. The heart and center of that alliance is the English-speaking triangle. Obviously we need the full help of our allies in continental Europe to make it a success, but it is just as obvious that they depend on our participation to make it a reality. . . . The chief problem that faces us here, and it has become a serious one of late, is to equate the maximum contribution we can bear with the minimum that we need for complete security. 1 dare say most of us have some doubts as to whether the equation has yet been solved. It seems that the two larger partners, facing up to the realization that the Cold War is going to be a very long pull, have felt compelled to choose between being strong for every eventuality or concentrating on being ready for the big blow-up. That may be logical and realistic for states that have the choice, but the rest of us are not sure where that leaves us. Are we the residuary legatees of conventional warfare? Perhaps Canada too could make a choice if she wanted to pay the price. We have the techniques; we have the raw material; we certainly have plenty of space for test explosions. Indeed, if we made a big enough bang and a big enough hole, we might uncover enough fissionable material in our northern rocks to go on indefinitely. We have no present intention of starting anything of the kind; but the situation does suggest that proper coordination in the sphere of defense may be a good deal less easy in the future than it was in the earlier stages.

There is a further side to the equation, and that is the reconciliation of military strength with economic and social stability. We want to be secure, but we want to be prosperous too; and what is more, we need associates who are prosperous and contented as well. . . . This is the principle implicit in Article II of the North Atlantic treaty. The initiative came from Canada, but no country is more aware of the importance of European stability than is Britain, and no country has done more to aid and encourage that stability than has the United States. . . .

Now the protective power of this Atlantic shield extends far beyond the Atlantic region. It pins down the main military strength of the Soviet bloc in one vital area; it inhibits the use of force and the threat of force against other areas that, left to themselves, could hardly stand up against the concentrated pressure of Soviet power. . . . Not all the newlyfreed nations recognize how vital this is to their own independent nationhood. It is because we western democracies are there to hold the line that less developed lands are free to choose their path of development, to experiment in safety with economic and political systems, to play around with foreign policies that may range from the piously neutral to the profanely malevolent. We need not claim that we are altruistic in this. We have as a fundamental interest the creation of a world in which our own values and our own freedoms will be secure; and perhaps the only world that is truly safe for democracy is a democratic world. So we must continue to hold the line, not only for the negative purpose of preventing new Communist seizures by force, but with the positive objective of winning those nations that are still uncommitted to our own ideology of liberty.

Time is essential for this, and there are heartening signs that time is having its effect. It has taken a while for the countries in question to become aware of the dangerous realities of the world into which they have so recently emerged; but as awareness grows, so does the sense of an identity of interest with the western democratic states and the readiness to make common cause with them. . . .

Our general interest may be as one; our specific interests frequently tend to diverge. We differ in the emphasis that we put on various problems. We are subject to divergent pulls, both economic and geographic. American stake in world trade, for instance, is less urgent than that of Britain and Canada; Britain's need for secure access to world resources is greater than that of either Canada or the United States. Britain has a set of varied pulls toward Europe, toward the Commonwealth, toward her remaining colonies, that are different from the external pulls experienced by her two associates. In consequence, the effort at a single united policy can be carried only so far; beyond that, it is reduced to a coordination of separate policies, or even to a recognition of inevitable divergencies and a conscious attempt to keep them to the minimum in the interests of overall harmony.

This task becomes particularly complicated, though certainly not less urgent, when we come to the United Nations. Here we are repeatedly presented with problems that tend to accentuate our differences of interests and approach. It is much harder, in this world organization, to select areas or aspects in which our common interests are specifically engaged. We have to operate within a global framework, and to take account of the vociferous views of countries with which we have little direct concern and groups on which we can exercise only a minimum leverage. . . .

This is something we have to bear as best we can. The United Nations is one of the facts of life, and much too important a fact for us to treat with indifference. I happen to believe that as an institution it is not only inevitable but desirable, and that without it, world conditions would be even more difficult than they are today. What we must try to do is to live with it and make the best of it, and especially to recognize that in this field, just because of its special difficulties, the need for our three countries to make special efforts at agreement based on compromise is of prime im- portance to the effectiveness of our cooperation in other fields of action. . . .

Every good thing has its price; and the fundamental unity of our three nations is such a unique asset, not only for ourselves but for the whole of the free world, that even a high price in terms of compromise and national renunciation is hardly too much to pay.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

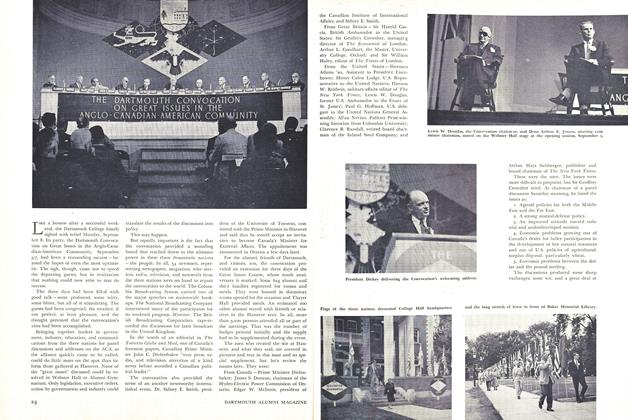

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePro Bono Publico

JANUARY 1973 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

JUNE • 1986 -

Cover Story

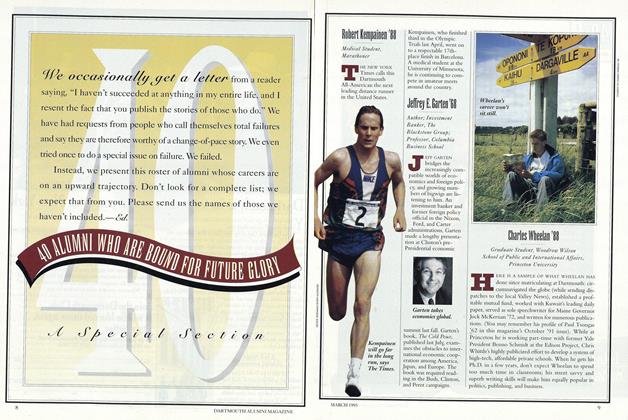

Cover StoryCharles Wheelan '88

March 1993 -

FEATURES

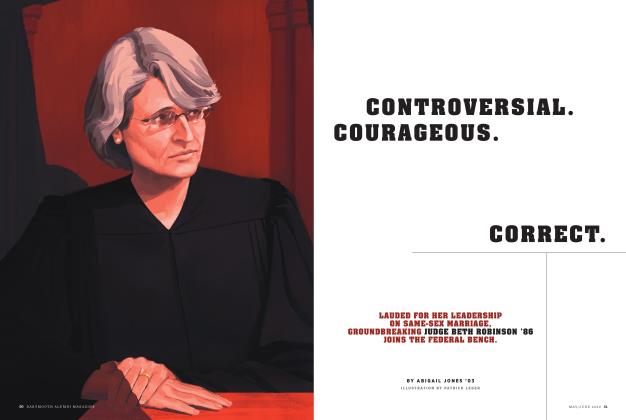

FEATURESControversial. Courageous. Correct.

MAY | JUNE 2022 By ABIGAIL JONES ’03 -

Feature

FeatureThe Computer Goes Fishing

September 1975 By DARREL MANSELL -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Fixer

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By Matthew Mosk ’92