The Presidency of Dartmouth College is an impossible job. It is impossible because no human being possesses all the talents expected of the Dartmouth President. And if such a human being were miraculously found, he would quickly learn that an 80-hour week is not long enough to do all the things he is expected to do.

Each constituency sees Dartmouth from a different point of view. The students are aware of the faculty and have frequent contact with student deans. The faculty is aware of the students and of the academic administrators. Most employees of the College see only a very small portion of Dartmouth. The alumni know the administrators in Crosby Hall and follow Dartmouth sports; they may also know a few students and faculty members personally. While all of these constituencies are aware of the President, each has a rather hazy idea of what the President is supposed to do. Therefore, just what does the President of Dartmouth College do?

First of all, he is chief executive officer of an institution that has over 2,500 employees and a gross budget of over $5O million. It is a highly complex enterprise both academically and in its auxiliary activities. While academically it is a predominantly undergraduate dergraduateinstitution, to the President it presents all the complexities of a university. And since it is a residential college that is nearly as old as the town where it is located, it not only assumes such traditional functions as housing and feeding thousands of students but also provides a vast number of services normally not associated with a college. We provide housing, for hundreds of employees; we own a hotel, a ski resort, a golf course; we provide a vast array of entertainment; and we have fairly sizable land holdings. While most offices deal only with some small portion of the total activities of Dartmouth, the President is called upon to make decisions affecting all these enterprises. There are times when it is not clear whether he is president of a university or chief executive officer of a conglomerate.

Ultimate authority for the College rests in its Board of Trustees. The President is both a member of the Board and the officer responsible for its staff work. His responsibility is to see that the Board is fully briefed on all major issues and that the Board is well prepared for any decisions it has to make. In comparison with other institutions, Dartmouth is blessed by having a small and extremely active Board of Trustees. It is very rare to have more than one elected member absent from a meeting and, more often than not, every single elected member is present. I have been told by one of the senior Trustees that there has been a notable increase in Board activity in the past five years. The full Board meets four times a year, and every member serves on one or more committees and often on several other decision-making odies such as the various boards of overseers. As the Trustees have become more active, much greater demands have been made upon the President and upon his executive assistant, A. Alexander Fanelli '42. Since a highly active Board is very important for the future welfare of the College, both Alex Fanelli and I have welcomed our additional responsibilities.

The President is chairman of the General Faculty and of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. In addition, he chairs three faculty committees and periodically meets with other faculty groups. All faculties have an ambivalent feeling towards their president. On the one hand they look to him for leadership; on the other hand they may resent it when he attempts to lead them.

I have read articles that claim that the power of the college president has completely eroded. This is simply not true. It is true that faculties have been given a great deal more power to shape their own destinies. As a long-time faculty member, I believe in this and have helped strengthen the power of the various faculties. Yet considerable power is retained by "the administration." Most important of course is the control of the budget, but equally important is the responsibility to call to the faculty's attention problems that have arisen, and occasionally to suggest solutions to these problems. While most academic decisions are best left to the faculty's own initiative, there are certain major developments that could never take place without the active leadership of the administration. In a modern university these decisions are so complex that no one person could possibly carry them out. Therefore the President's most important academic role is to select first-rate people as academic deans, to work with them closely, and to give them his full support.

By tradition, the President of Dartmouth is the chief contact between the alumni and the College. Since no other academic institution in the country depends as heavily on its alumni for support, no Dartmouth President can afford to neglect this very important responsibility. I have tried to maintain close relations with the alumni both through traditional and new means. I visit 12 to 14 alumni clubs each year. With our far-flung alumni organization, the President can visit most clubs only infrequently, so I have tried to schedule as many different events as possible in connection with a visit. Wherever possible, in addition to the traditional cocktails and alumni banquet, I have tried to work in meetings with smaller groups, speeches to high school counselors and prospective students, press and TV interviews, and anything else that the local alumni club would find helpful. The alumni tour is perhaps the most tiring duty I have to carry out, and also one of the most rewarding.

Here in Hanover I have tried to speak to as many alumni groups as possible. I take part in six Dartmouth Horizons programs a year, meet with reunion classes, speak to most of the major alumni organizations that have Hanover meetings, and try to find special occasions - such as major football games - to make myself available to answer questions from groups of alumni. But. my single most effective means of communication with the alumni body has been The Bulletin. For the past few years I have written three of the ten Bulletins each year. The fact that I spend more time with alumni than my fellow college presidents, and much less time in Washington, shows where I believe the future welfare of Dartmouth College lies.

The Dartmouth alumni organization is the envy of all other institutions. While much of the credit goes to thousands of volunteer workers, the secret of success has always been the quality of the secretary of the College. Mike McGean '49 carries on a great tradition with devotion and an inexhaustible supply of good cheer.

Dartmouth College relies on annual gifts not only for strengthening its endowment but for a major portion of its operating budget. While we have a highly competent fund-raising staff under the leadership of George Colton '35 and Ad Winship '42, the President must remain the chief fund-raising officer of the College. He must map out the overall strategy for fund raising, make the case for Dartmouth College as a whole or for one of its many branches, and in special circumstances he alone can make the presentation to a potential donor.

In the final analysis, students are the reason for Dartmouth's existence. I have tried to get to know as many students as possible both inside and outside the classroom. A very useful means has been weekly office hours that are open only to Dartmouth students. No matter how crowded my schedule gets, a student can always see me between 1:30 and 3:00 p.m. on Tuesdays without an appointment. I have also held discussion sessions at dormitories and fraternities and periodic news conferences with the student press on WDCR. A happy innovation has been the use of students as administrative interns in several offices. I have been lucky to have as an assistant first a young alumnus, Win Rockwell '70, and then three fine student interns, Mike Hollis, John Hart, and Zenas Hutcheson, all of the Class of '75.

In spite of all of these attempts, the increase in the size of the student body and the much more complex responsibilities of the President will mean that each President of Dartmouth will know a smaller fraction of the students personally. The role of "substitute parent" has fallen more heavily on the shoulders of the dean of the College, the dean of freshmen and their associates, with the President becoming a court of last resort. This has probably been one of the unfavorable by-products of the increase in the size and complexity of the College during the 20th century. Fortunately, the great majority of our faculty members take a close and active interest in their students, and this continues to distinguish Dartmouth from most other academic institutions.

In addition to these important activities the President cannot escape serving as a ceremonial "chief of state." I once observed to the dean of the faculty: "If you show up at a ceremony everyone says 'wasn't it nice of Dean Rieser to come'; if I fail to show up at a ceremony, everyone wants to know why the President was absent." While I fully understand the importance of the institution being symbolically represented by its chief officer on ceremonial occasions, I must confess that there are times when I feel the hours could be better spent otherwise. The Presidency of Dartmouth is the only job I know where you are elected first and then spend your remaining years as if you were running for office.

I have elected to remain an active member of the faculty. In the past five years I have taught nine courses. They have all been on the undergraduate level, and several of them have been freshman courses. One was a seminar in philosophy, several have dealt with computers, and the rest were mathematics courses. My main reason for continuing to teach is the simple fact that I've always loved teaching. But it has also been a good way to stay in touch with students and to be continually reminded of what the fundamental purpose of the College is. Teaching has also proved to be an excellent antidote to the frequent frustrations of the job.

Inevitably, the President serves as the chief complaints officer of the College. As with any bureaucracy, people get frustrated and don't know where to turn. As a last resort they turn to the President's office. This demand had become so time-consuming that I established the office of ombudsman which was ably filled first by Professor Emeritus William Carter '2O and then by Kathryn Chamberlin. Unfortunately, as we were forced to reduce the size of the administration for budgetary reasons, I had to abolish this office.

One of the most important functions of the President of any college is to coordinate long-range planning for the institution. It has been one of the sad consequences of our serious financial pressures that increasingly we have had to plan for the relatively short run. But the President must not allow immediate problems to prevent him from planning for the long-range welfare of the institution. Unlike many presidents, this is one task I have not been willing to delegate.

I have engaged in fewer "outside" activities than most other college presidents. For many, a college presidency has been a national platform used either to build up a career or to participate in nationwide decision-making. I find that my Dartmouth responsibilities consume all of my time and therefore I feel guilty when I engage in any non-Dartmouth activity. I served a two-year term as a member of the National Commission on Libraries and Information Science. I have also served on the board of trustees of the Foundation Center (which provides information on all foundations) and of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. While I have turned down most invitations for lectures at other campuses, I have accepted one or two invitations a year. Most memorable of these was the invitation from the Museum of Natural History in New York where a lecture series led to the publication of my book, Man and TheComputer. I have, of course, served on a variety of organizations as a representative of Dartmouth, most notably the Ivy presidents group where I've just completed a two-year term as chairman.

I understand that one of the problems of modern civilization is that many people do not know what to do with their free time. I am happy to say that I have not faced that problem for the past five years! Perhaps it is appropriately symbolic that I am writing a first draft of this section on Christmas Eve.

The margin of survival has been supplied by my superb personal staff. Alex Fanelli, whom I mentioned before, and Lu Sterling - special assistant to the President - share the task of backing me up in all my work, keeping me briefed, representing me on countless occasions, and making sure that I do not drop one of the fifteen balls that I have to juggle at all times. And my secretary, Ruth LaBombard, is the one who keeps the three of us going. Their loyalty, devotion, and willingness to work endless hours has meant a great deal to me and I can never sufficiently acknowledge my indebtedness to them.

Even with the best possible staff, the Presidency would have been impossible for me without the help and support I receive from my wife. Most people know her only in her role as a hostess at some 100 events each year. Few know how thoroughly she has briefed herself on the affairs 'of the College, and how ably she serves as a spokesman for the College as she shares the alumni tour with me, and at countless events in Hanover. Above all she is the one person with whom I can share all my problems. Someone once asked me how I manage to sleep at night. I confessed that I had a simple secret: each evening I told my wife about all my problems and then I slept very soundly - and she stayed awake all night.

As Dartmouth is a unique institution, the Presidency of Dartmouth is a nearly unique job. Most institutions of higher education are either small colleges or large universities. Small colleges do not have nearly the complexity of Dartmouth, and in a large university the President is shielded from most of his constituencies. It is one of the great strengths of Dartmouth that each faculty member, each student, each alumnus, and each employee feels free to come directly to the President. It is this fact that makes the Presidency of Dartmouth one of the most demanding and complex jobs in the country - and one of the most fascinating and satisfying.

Features

-

Feature

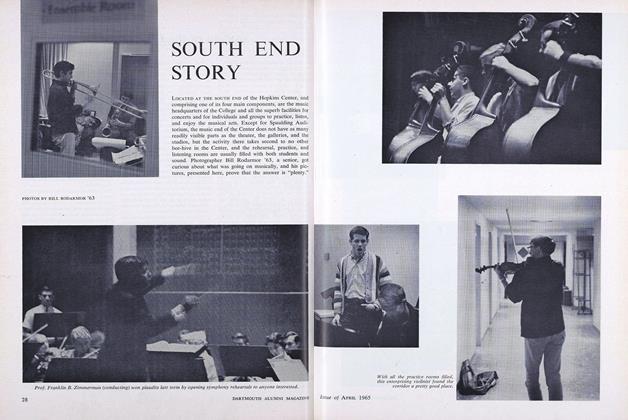

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

APRIL 1965 -

Feature

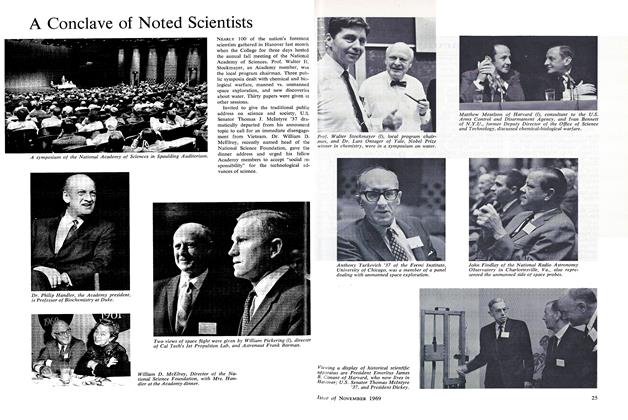

FeatureA Conclave of Noted Scientists

NOVEMBER 1969 -

Cover Story

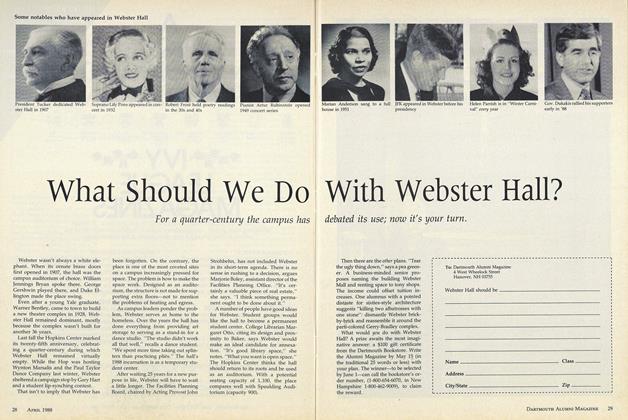

Cover StoryWhat Should We Do With Webster Hall?

APRIL 1988 -

Feature

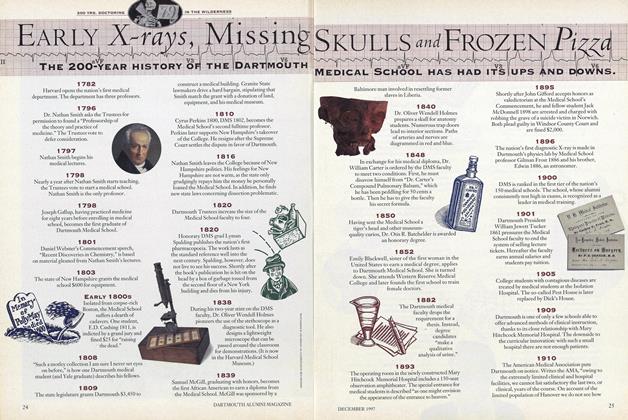

FeatureEarly X-rays, Missing Skulls and Frozen Pizza

DECEMBER 1997 -

Feature

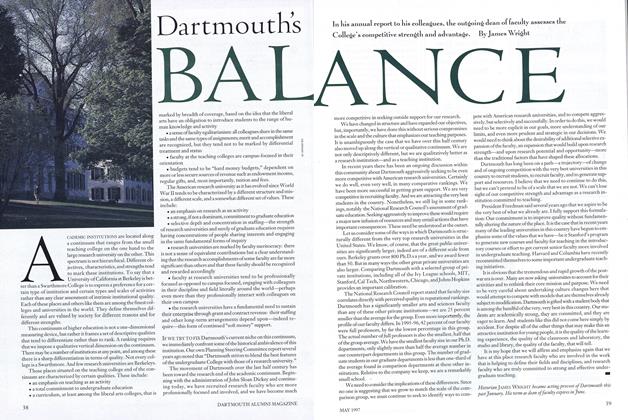

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

MAY 1997 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureThe Onlyness of a Long-Distance Runner

June 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75