RESPONDING to a request for information about some of the formative influences in the early years of his life. President Hopkins in 1943, two years before his retirement, wrote to the late Prof. John M. Mecklin that he counted the association with Dr. William Jewett Tucker as the greatest privilege of his life; and then he added:

"I can say very sincerely and without the slightest trace of affectation that I haven't done anything except build upon foundations which were laid deep enough and solid enough for any superstructure during the administration of Dr. Tucker. Whatever merit there may be in Dartmouth today goes back to the work he did under infinitely greater difficulties and calling for greater expenditure of thought and effort than has been required at any time since."

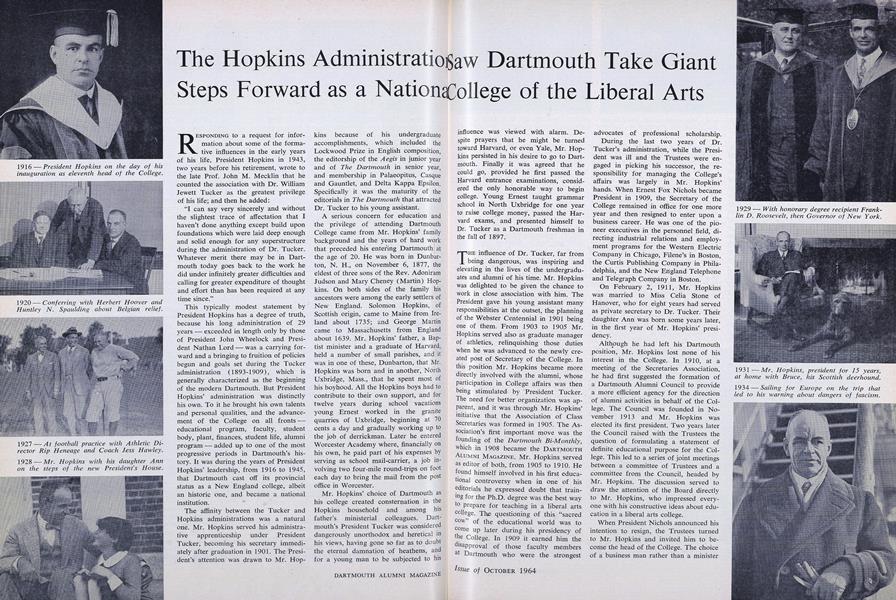

This typically modest statement by President Hopkins has a degree of truth, because his long administration of 29 years - exceeded in length only by those of President John Wheelock and President Nathan Lord - was a carrying forward and a bringing to fruition of policies begun and goals set during the Tucker administration (1893-1909), which is generally characterized as the beginning of the modern Dartmouth. But President Hopkins' administration was distinctly his own. To it he brought his own talents and personal qualities, and the advancement of the College on all fronts - educational program, faculty, student body, plant, finances, student life, alumni program - added up to one of the most progressive periods in Dartmouth's history. It was during the years of President Hopkins' leadership, from 1916 to 1945, that Dartmouth cast off its provincial status as a New England college, albeit an historic one, and became a national institution.

The affinity between the Tucker and Hopkins administrations was a natural one. Mr. Hopkins served his administrative apprenticeship under President Tucker, becoming his secretary immediately after graduation in 1901. The President's attention was drawn to Mr. Hopkins because of his undergraduate accomplishments, which included the Lockwood Prize in English composition, the editorship of the Aegis in junior year and of The Dartmouth in senior year, and membership in Palaeopitus, Casque and Gauntlet, and Delta Kappa Epsilon. Specifically it was the maturity of the editorials in The Dartmouth that attracted Dr. Tucker to his young assistant.

A serious concern for education and the privilege of attending Dartmouth College came from Mr. Hopkins' family background and the years of hard work that preceded his entering Dartmouth at the age of 20. He was born in Dunbarton, N.H., on November 6, 1877, the eldest of three sons of the Rev. Adoniram Judson and Mary Cheney (Martin) Hopkins. On both sides of the family his ancestors were among the early settlers of New England. Solomon Hopkins, of Scottish origin, came to Maine from Ireland about 1735; and George Martin came to Massachusetts from England about 1639. Mr. Hopkins' father, a Baptist minister and a graduate of Harvard, held a number of small parishes, and it was in one of these, Dunbarton, that Mr. Hopkins was born and in another, Norih Uxbridge, Mass., that he spent most of his boyhood. All the Hopkins boys had to contribute to their own support, and for twelve years during school vacations young Ernest worked in the granite quarries of Uxbridge, beginning at 70 cents a day and gradually working up to the job of derrickman. Later he entered Worcester Academy where, financially on his own, he paid part of his expenses by serving as school mail-carrier, a job involving two four-mile round-trips on foot each day to bring the mail from the post office in Worcester.

Mr. Hopkins' choice of Dartmouth as his college created consternation in the Hopkins household and among his father's ministerial colleagues. Dartmouth's President Tucker was considered dangerously unorthodox and heretical in his views, having gone so far as to doubt the eternal damnation of heathens, and for a young man to be subjected to his influence was viewed with alarm. Despite prayers that he might be turned toward Harvard, or even Yale, Mr. Hopkins persisted in his desire to go to Dartmouth. Finally it was agreed that he could go, provided he first passed the Harvard entrance examinations, considered the only honorable way to begin college. Young Ernest taught grammar school in North Uxbridge for one year to raise college money, passed the Harvard exams, and presented himself to Dr. Tucker as a Dartmouth freshman in the fall of 1897.

THE influence of Dr. Tucker, far from being dangerous, was inspiring and elevating in the lives of the undergraduates and alumni of his time. Mr. Hopkins was delighted to be given the chance to work in close association with him. The President gave his young assistant many responsibilities at the outset, the planning of the Webster Centennial in 1901 being one of them. From 1903 to 1905 Mr. Hopkins served also as graduate manager of athletics, relinquishing those duties when he was advanced to the newly created post of Secretary of the College. In this position Mr. Hopkins became more directly involved with the alumni, whose participation in College affairs was then being stimulated by "President Tucker. The need for better organization was apparent, and it was through Mr. Hopkins' initiative that the Association of Class Secretaries was formed in 1905. The Association's first important move was the founding of the Dartmouth Bi-Monthly, which in 1908 became the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Mr. Hopkins served as editor of both, from 1905 to 1910. He found himself involved in his first educational controversy when in one of his editorials he expressed doubt that training for the Ph.D. degree was the best way to prepare for teaching in a liberal arts college. The questioning of this "sacred cow" of the educational world was to come up later during his presidency of the College. In 1909 it earned him the disapproval of those faculty members at Dartmouth who were the strongest advocates of professional scholarship.

During the last two years of Dr. Tucker's administration, while the President was ill and the Trustees were engaged in picking his successor, the responsibility for managing the College's affairs was largely in Mr. Hopkins' hands. When Ernest Fox Nichols became President in 1909, the Secretary of the College remained in office for one more year and then resigned to enter upon a business career. He was one of the pioneer executives in the personnel field, directing industrial relations and employment programs for the Western Electric Company in Chicago, Filene's in Boston, the Curtis Publishing Company in Philadelphia, and the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company in Boston.

On February 2, 1911, Mr. Hopkins was married to Miss Celia Stone of Hanover, who for eight years had served as private secretary to Dr. Tucker. Their daughter Ann was born some years later, in the first year of Mr. Hopkins' presidency.

Although he had left his Dartmouth position, Mr. Hopkins lost none of his interest in the College. In 1910, at a meeting of the Secretaries Association, he had first suggested the formation of a Dartmouth Alumni Council to provide a more efficient agency for the direction of alumni activities in behalf of the College. The Council was founded in November 1913 and Mr. Hopkins was elected its first president. Two years later the Council raised with the Trustees the question of formulating a statement of definite educational purpose for the College. This led to a series of joint meetings between a committee of Trustees and a committee from the Council, headed by Mr. Hopkins. The discussion served to draw the attention of the Board directly to Mr. Hopkins, who impressed everyone with his constructive ideas about education in a liberal arts college.

When President Nichols announced his intention to resign, the Trustees turned to Mr. Hopkins and invited him to become the head of the College. The choice of a business man rather than a minister or professional educator created immediate opposition in some faculty and alumni quarters, and raised eyebrows in the academic world. In his introduction to This Our Purpose, the collection of Hopkins addresses and writings published in 1950, Mr. Hopkins discusses this "academic agnosticism" in regard to his election and writes: "My original reservations in regard to my ability to conform to the conventional picture of a college presidency gradually evolved into a question of whether I could render to Dartmouth College the particular service needful to perpetuation of the specific qualities which had distinguished her through a century and a half. In what is perhaps an excess of frankness, I believed I could more certainly than could any other whose name remained on the list of eligibles."

By his inaugural address and his performance on the job at the outset of his administration Mr. Hopkins very quickly dissipated the misgivings and won enthusiastic support on all sides with his definition of high educational purpose, his open-mindedness, his administrative skill, and his warm personal leadership. The faculty found him no less a devotee of scholastic excellence than themselves, and they were delighted to find that their ideas were listened to with understanding and adopted when feasible.

THE new President devoted himself untiringly to visits to the alumni. In his inaugural address he had made a special point of stating his belief that in the alumni resided one of Dartmouth's greatest resources. "There will be few such possibilities of added vigor to the College as in the development of what has come to be known as the alumni movement," he said. His address of nearly fifty years ago was noteworthy also for its inclusion of perhaps the first proposal of what is now commonly called "continuing education" for the alumni. His awareness of the potential of alumni support, learned from Dr. Tucker, and his sedulous development of it early gave Dartmouth a distinctive leadership in this area of college effort that it has not lost to this day.

In his addresses to the alumni all over the country President Hopkins did not talk down to them. He discussed with them the serious educational aims of the College and convinced them that Dartmouth had a large and vital role to play in the welfare of the nation. The historic purpose of the liberal arts college was constantly his theme. The result was that the President's high seriousness and dedication, coupled with the magnetism of his warm-hearted personality, won him the enthusiastic and affectionate backing of Dartmouth men, to whom he increasingly became "Hoppy," the embodiment of all that the College stood for.

Early in his presidency Mr. Hopkins was called to Washington for government service in World War I. With his background of industrial experience, he was placed in charge of industrial relations for the Quartermaster General's division of the War Department, January to June 1918, and then he became assistant to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker in charge of all industrial relations for the Department. When Mr. Hopkins returned to Dartmouth in September 1918, the Secretary praised his work in relieving him of all questions of labor policy and helping to asssure a steady flow of war supplies.

Back on the job in Hanover, President Hopkins settled down to a review of the College's educational program. A revised curriculum was adopted in 1919, the most novel feature being certain orientation work required of all freshmen. Departmental organization was radically changed about this time, and a more democratic system replaced the excessive authority held by the department chairmen. Earlier, in 1917, faculty tenure had been fixed by Trustee resolution, and machinery provided for faculty advice on appointments and promotions.

A more thorough study of Dartmouth's curriculum and educational procedures was undertaken in 1923-24, in part by an undergraduate committee, which produced a report of remarkable maturity and of interest to colleges throughout the land, and in major part by the Committee on Educational Policy, headed by Prof. Leon Burr Richardson '00. Out of it came the educational plan that in broad outline is still in effect today. The new curriculum eliminated the distinction in bachelor degrees in favor of the A.B. for all graduates, expanded and gave a new emphasis to coherent major study in the last two years, required a comprehensive examination as prerequisite to the degree, established honor courses for outstanding students, and set certain freshman-year requirements as well as distributive requirements in the first two years. In 1929 the Senior Fellowships were added for men especially capable of setting their own academic pace, and interdepartmental programs were also introduced to underscore the growing relationship of the different fields of knowledge.

While putting primary emphasis on the intellectual objectives of the College, President Hopkins was at the same time determined that Dartmouth as an undergraduate liberal arts college should not think of its students as "disembodied intellects," as he put it. He encouraged the outdoor life of the student body, led by the Outing Club, and was an unabashed advocate of intercollegiate athletics, so long as they were kept in their proper place in relation to the educational purposes of the college. He was an enthusiastic follower of the Dartmouth teams, and during the fall was frequently seen on Memorial Field watching football practice.

President Hopkins missed no opportunity to state his belief in the importance of the human element in college education. At the inauguration of his brother, the late Louis B. Hopkins 'OB, as President of Wabash College, he declared: "The organization of the American college is fundamentally designed to make educational advantage increasingly an influence in the lives of human beings. He who becomes oblivious of the attributes of human beings in seeking to learn the principles of educational method misses the point of his responsibility."

For Mr. Hopkins education was incomplete until men of character had put it to use for the general good. This belief as much as the growing flood of applicants for admission to Dartmouth in the years after World War I was a factor in the adoption of the then unique Selective Process of Admission in 1921. The College announced that the men in the entering class would henceforth be chosen not only for intellectual capacity, which was the primary requisite, but also for broad interests, character, initiative, and all-around ability. This admissions policy, greeted in the academic world with skepticism and some suspicion that it was really a means of favoring athletes, has since been generally adopted by the leading colleges and universities in the land. Later, the College broke away from the standard procedure of requiring a set number of units in prescribed preparatory courses and based admission on evidence that the applicant was prepared to do college work.

A WILLINGNESS to grant undergraduates responsibility for campus affairs in direct proportion to their demonstrated ability to handle it was always a part of President Hopkins' philosophy in his dealings with the student body. One of the first acts of his presidency was to drop the policy of having all outside lecturers chosen by the President's Office and to make the funds available to student organizations so they could hear speakers of their own choice. He gave undergraduates membership on certain administrative committees, and in assigning them an important role in the curriculum study of 1923-24 he showed his faith in their ability and responsibility.

In his concern that conditions of student life should advantageously supplement the academic program, President Hopkins by fiat in 1924 banned the pledging of freshmen to fraternities. He declared that "mental hygiene" was a new realm in which the colleges must safeguard the student, and in 1921 Dartmouth became one of the first colleges to provide for this need by adding a consultant in mental hygiene to the staff. In 1935 an elaborate social survey was made by a special committee, resulting in the construction of Thayer Hall as an upperclass dining center and in general improvement of fraternity life by putting the national organizations on notice that their continued existence at Dartmouth depended on their making a more positive contribution to the College. In the same year, a health insurance program for all students was adopted; and in 1938 another special study produced plans for a large auditorium and student center, which was never realized until later studies and revised plans resulted in the construction of Hopkins Center as one of the major events of President Dickey's administration.

In addressing the Dartmouth students, President Hopkins sometimes scolded them for their failure to realize the golden opportunity of their college years, and in his famous "aristocracy of brains" address he flatly asserted that too many men were in college who had no business being there. As the United States approached involvement in World War II, he was angered by undergraduates of that period who advocated peace at any cost. He called them the "hitch-hiking generation" and spoke critically of their concern with security, their self-pity, and their seeming lack of responsibility for earning the freedoms they enjoyed. To the graduating class of 1937 he said, "No real friend of yours could wish that you should never face misfortune, that you should never undergo hardship, that you should never be beset by difficulties. It is not so that vigor of mind or strength of character is developed."

This was a passing interlude, however, in the long period of years in which Mr. Hopkins demonstrated his delight and confidence in his "Dartmouth boys." He especially trusted their ability to make up their own minds on the basis of divergent points of view presented to them. "The function of an educational institution is to allow men access to different points of view and to secure their adherence to conclusions on the basis of their own thinking rather than to attempt to corral them within given mental areas," he said in 1925. Besides, he added, "repression and censorship never work within an intellectually alert group of boys such as constitute the college."

He shocked many by stating that he would be willing to have Lenin and Trotsky address the Dartmouth students if they would come. In 1922 he reproved a group of fundamentalists in his own Baptist denomination who urged him to weed out "heretical" teaching by the Dartmouth faculty. At the same time he welcomed William Jennings Bryan, the leading champion of fundamentalism, to a Dartmouth platform.

These acts were in keeping with President Hopkins' liberal character. He was a life-long champion of freedom of inquiry and expression, and vigorously protected these principles throughout his administration. When one irate alumnus offered $50,000 if he would fire a professor who had criticized the 1921 Sacco-Vanzetti trial decision by Judge Webster Thayer, himself a Dartmouth man, Mr. Hopkins told the disturbed professor: "Don't get excited. If you quit, I will too, and we'll split the $50,000."

The eminent sociologist, John Moffatt Mecklin, was given haven at Dartmouth after stormy teaching careers elsewhere because of his unorthodox views. In his book, My Quest for Freedom, he wrote of Mr. Hopkins: "Here was a college president of the type I had often heard about but had never known in the flesh. Cordial, courteous, tolerant, he discussed with me the proposed position. He gave me complete freedom to teach what I had long wished to teach."

President Hopkins' staunch defense of academic freedom gave courage to other colleges. His liberal stance, his independence in charting Dartmouth's course, his championship of the liberal arts college, his willingness to speak his mind, all made him a highly respected and widely known figure in the world of higher education. The nation's press also paid respectful attention to what he had to say, and the fact that he was a "quotable" man did nothing to diminish this coverage. Mr. Hopkins did not confine his outspoken views to education, although that was his chief subject. In 1931 he announced his opposition to the continuance of national prohibition. Upon returning from Europe in 1934 he warned of the spreading evil of fascism and expressed concern over the danger to the free world unless it took steps to protect itself.

PRESIDENT Hopkins was given a hearing also, by both Dartmouth men and others, when he sought financial support for the College. When he took over the presidency in 1916, Dartmouth had little endowment and total assets of only $5,965,000. When he retired in 1945, the College had an endowment of more than $20-million and total assets of $31,243,000. The faculty had grown from 150 to 275 members, with 64% of an annual budget of $2-million devoted to instructional purposes; the student body had increased from 1400 to the 2500 to which the Trustees had voted to limit it; and the educational plant had quadrupled in value to $7,500,000.

Except in Wilder physics laboratory, Shattuck Observatory, and the Medical School, no teaching at Dartmouth in 1945 was done except in buildings erected or completely remodeled during the Hopkins administration. Among new additions to the plant were the Carpenter Fine Arts Building, the Horace Cummings Memorial housing the engineering school, Silsby Natural Sciences Building, the present Tuck School of Business Administration, Sanborn English House, Steele Chemistry Building, Dick Hall's House, Thayer Hall, the President's House, twelve dormitories, and much of the present-day athletic plant.

Foremost addition of all was the Baker Memorial Library, erected in 1928 through the gift of a million dollars from George F. Baker of New York. Endowed by Mr. Baker with another million and enabled to purchase books with income from a million-dollar gift by Edwin Webster Sanborn '7B, Baker Library from the start was the outstanding undergraduate college library in the country, and still has that distinction. Nothing in the long history of the College provided such a stimulus to Dartmouth's educational growth as the arrival of Baker Library on the Hanover scene.

The friendship between President Hop-kins and Edward Tuck, Class of 1862, was an important factor in the strengthening of Dartmouth's endowment and educational plant. The Alumni Fund, established by the Alumni Council in its very first year when Mr. Hopkins was its president, grew steadily during the Hop-kins administration and laid the foundation for the spectacular results being realized today under President Dickey's leadership.

Answers to the financial problems of the College were not easily found during the Hopkins administration, which embraced two World Wars and the Great Depression of 1929-33. With civilian enrollment down from 2500 to as little as 160 men during World War II, Dartmouth, which had been the first college in the country to accelerate its academic program, had the good fortune to become the site first of a naval indoctrination school and then of the largest Navy V-12 unit in the country.

On the eve of World War II, President Hopkins returned to Washington as executive director of the minerals and metals section of the OPM Priorities Division under Edward R. Stettinius Jr. In 1944 he accepted the national chairmanship of Americans United for World Organization, which worked for United States acceptance of the United Nations Charter. After V-J Day the Secretary of the Navy appointed him chairman of a commission to investigate the naval administration of civilian affairs on Guam and Samoa.

THROUGHOUT his Dartmouth presidency Mr. Hopkins was called upon for important outside positions. In 1933 President Roosevelt named him special investigator of political and educational conditions in Puerto Rico. He was a member of the Board of Visitors of the U. S. Naval Academy in 1937-38, and in 1942 he served as chairman of a special board of civilian and military educators named to review the accelerated wartime curriculum at West Point. He was president of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation in 1933, a member of the Rockefeller Foundation from 1928 to 1942, and in 1939 he succeeded John D. Rockefeller Jr. as chairman of the General Education Board. He was on the first board of governors of the Arctic Institute of North America, and at various times was a trustee of Worcester Academy, Phillips Academy at Andover, The Brookings Institution, Newton Theological Seminary, and The Cardigan Mountain School, which he helped to found.

Mr. Hopkins kept in touch with the business world as a director of the Boston and Maine Railroad, Continental Can Company, the Brown Company, New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, Rumford Press, H.P. Hood & Sons, and the National Life Insurance Company of Montpelier, Vt.

He received seventeen honorary degrees - from Amherst, Bowdoin, Brown, Colby, Dartmouth, Harvard, Hobart, Mc-Gill, Middlebury, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Rutgers, St. John's, Wabash, William and Mary, Williams, and Yale. In 1922 the University of Chicago conferred a special sort of honor upon him by inviting him to become its president, but Mr. Hopkins preferred to remain at Dartmouth working for the advancement of undergraduate liberal arts education.

In politics he was an independent Republican, and although he never became a candidate for any office, he was influential in party councils and was frequently urged to run for national office. He always put off these proposals with the statement that he aspired to no greater honor than the presidency of Dartmouth College. In 1928 he did serve as Republican presidential elector from New Hampshire.

Although he had wished to retire in 1942, at the age of 65, Mr. Hopkins was persuaded by the Trustees to remain in office and give his experienced leadership to the College during World War II. At the war's end he was able to fulfill his earlier wish and on November 1, 1945 he relinquished the presidency to John Sloan Dickey of the Class of 1929. The college he turned over to President Dickey was a vastly greater institution than the one he had accepted from President Nichols 29 years before.

In his remarks at the inauguration of President Dickey, whose first official act was .to confer Dartmouth's honorary Doctorate of Laws on him, Mr. Hopkins said, "It has been a joyful period and I have had a happy time. I have known that I have dwelt among friends. I have known that support and confidence were available when they were needed. ... It is in my deep conviction that in the new leadership of the College you have one who understands the treasures to be conferred by Dartmouth and who, from my point of view even more important, understands the spirit, that I have the happiness in this occasion and in the anticipation of years to come."

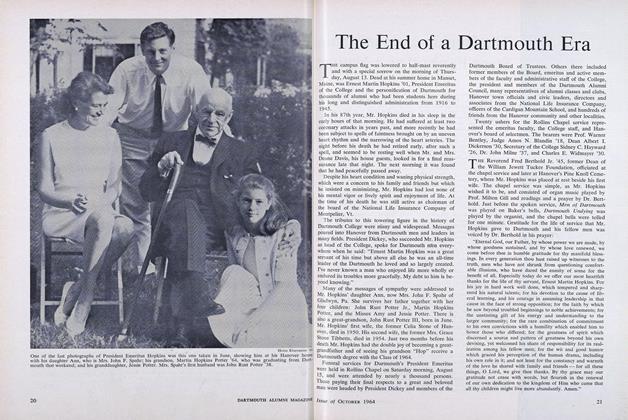

IN the years after retirement Mr. Hop-kins continued to make his home in Hanover, at 29 Rope Ferry Road. He made a special point of remaining in the background of Dartmouth's official life, but his presence was desired at all important events and he did participate in major convocations and in several Commencements. He escorted President Eisenhower in the 1953 academic procession and last June he was a colorful figure at the graduation exercises in which his grandson "Hop" received his degree.

President Emeritus Hopkins' Dartmouth activities were related mainly to the alumni, who showered him with invitations to attend their class and club events and who visited him at his home when they were in Hanover. Some of the major occasions of his retirement years were the tributes paid to him by alumni organizations. He was the first recipient of the annual Dartmouth Alumni Awards instituted by the Alumni Council in 1954. To pay tribute to him on his 80th birthday, 2200 persons jammed the main ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York on February 5, 1958 (three months late) for one of the great alumni gatherings in Dartmouth's history. Mr. Hopkins was the central figure at siteclearing ceremonies for the Hopkins Center in October 1958 and again when the Center was dedicated in November 1962. He was the guest of honor at the 50th anniversary dinner of the Alumni Council in June 1963 and at the 50th anniversary dinner of the Alumni Fund and the 100th anniversary dinner of the Boston Alumni Association, both in January 1964. Another honor paid him was the October 1958 dedication of Hopkins Hall, scholastic center of the Cardigan Mountain School, which he had helped to found in 1945 and which he continued to serve as a member of the corporation.

Beyond the College, President Emeritus Hopkins had many active interests and the earliest of his retirement years were busy ones. He retained his directorships in several companies, including the National Life Insurance Company which in 1948 elected him president to direct a reorganization. In 1950 he became the company's board chairman, a position he held up to the time of his death.

President Emeritus Hopkins knew the sorrow of losing two wives within the short space of four years. Mrs. Celia Stone Hopkins died in May 1950, and a year and a half later Mr. Hopkins married her sister, Mrs. Grace Tibbetts of Hanover, widow of Howard M. Tibbetts, registrar of the College from 1908 until he died in 1922. The second Mrs. Hop-kins died in June 1954.

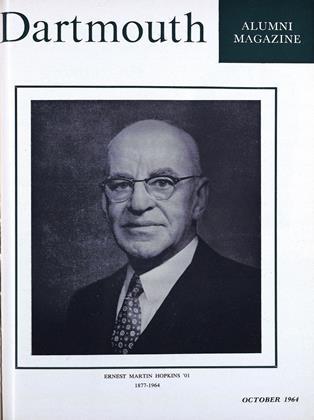

During the past two or three years, as he courageously contended with a serious heart condition and increasing infirmity, Mr. Hopkins reduced his activities and remained more at home, but he was still mentally keen, interested in Dartmouth and world affairs, and as kind and hospitable as ever. Most of the companions of his own time had passed away; his brothers, Louis B. Hopkins '08 and Robert C. Hopkins '14, had both died; and his most intimate interest was centered more and more on his daughter Ann and his four grandchildren. He had the joy of being surrounded by this family group during the month of July in Maine, where quietly and with the simplicity and dignity so characteristic of his whole life he died on August 13, 1964.

1916 - President Hopkins on the day of hisinauguration as eleventh head of the College.

1920 — Conferring with Herbert Hoover andHuntley N. Spaulding about Belgian relief.

1927 - At football practice with Athletic Director Rip Heneage and Coach Jess Hawley.

1928 - Mr. Hopkins with his daughter Annon the steps of the new President's House.

1929 - With honorary degree recipient Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Governor of New York.

1931 — Mr. Hopkins, president for 15 years,at home with Bruce, his Scottish deerhound.

1934 - Sailing for Europe on the trip thatled to his warning about dangers of fascism.

1936 - Pres. Hopkins signing one of 15,000matriculation certificates done in 29 years.

1937 — At the inauguration of EdmundEzra Day '05 as the President of Cornell.

1939 - President and Mrs. Hopkins in Virginia during a tour of alumni clubs in the South,

1941 - At graduation exercises in the Bema heawards 500 of the thousands of degrees he gave.

1941 - Cutting his "birthday" cake at partygiven by the faculty on his 25th anniversary.

1942 - With Professors Scarlett and Messerhe discusses matters of wartime instruction.

1945 - President Hopkins and President-Elect Dickey together in Maine inSeptember, the month before Dartmouth's present leader was inaugurated.

1951 - Pres. Hopkins with his second wife, theformer Mrs. Grace Stone Tibbetts of Hanover.

1953 - At Commencement he escorts PresidentEisenhower, who received an honorary degree.

1955 — At June alumni meeting he is salutedas first Dartmouth Alumni Award recipient.

1958 - To honor his 80th birthday, 2200 persons attended testimonial dinner in New York.

1958 - With Pres. Dickey and Architect Wallace Harrison at Hopkins Center site clearing.

1962 - President Hopkins in front of the Hopkins Center, now a fitting memorial to him.

1963 — Receiving 50th anniversary tribute as founder of the Alumni Council.

1964 - With President Dickey and Christian Hter at Commencement, his last official occasic

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSome Hopkins Views on Higher Education

October 1964 -

Feature

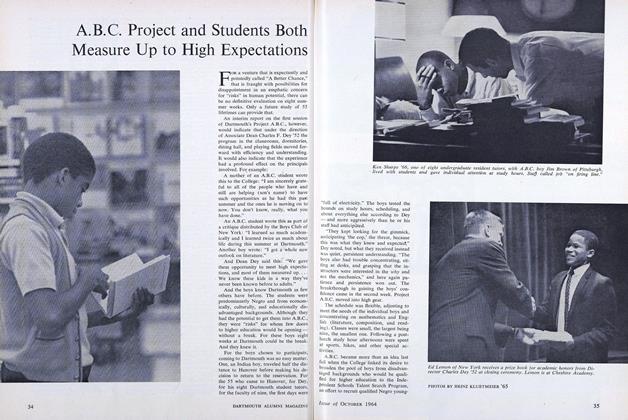

FeatureA.B.C. Project and Students Both Measure Up to High Expectations

October 1964 -

Feature

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

October 1964 -

Feature

Feature"This Considerate, Friendly Personality"

October 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1964

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMaster Translator

APRIL 1968 -

Feature

FeatureEngineering in the Limelight

NOVEMBER 1971 -

Feature

FeatureDROPPING OUT

January 1974 -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureSenior Valedictory

JULY 1972 By ROSS P. KINDERMANN '72 -

Feature

FeatureStudent Workshop

MAY 1957 By VIRGIL POLING