By the AmericanUniversities Field Staff, under the editorship of Prof. K. H. Silvert. New York:Random House, 1963.

The main themes of Expectant Peoples will be familiar to many of Dartmouth's most recent graduates. For older alumni the book should also be of interest, not only for its intrinsic value, but also as an outline of some of the ideas currently animating a sizable proportion of Dartmouth undergraduates. Professor Silvert's views - expounded in the introduction, conclusion, and one chapter of this volume - have captivated countless students and have stimulated not a few of the faculty, including the reviewer. This is a parochial note.

On another level, the book represents a significant effort to clarify thinking about development in the emerging nations. Expectant Peoples is a collaborative work of twelve associates of the American Universities Field Staff, all of whom have had extensive experience in several underdeveloped, or less-developed, countries. Each contributes a brief, generally illuminating analysis of the recent history and current problems of a country in which he has special competence.

The contributors' interests and opinions vary considerably - one, a journalist, is irritated by economic nationalism in the Philippines; another, a political scientist and sociologist, tends to sympathize with a similar phenomenon in Brazil. Different cultures and historical experiences raise different kinds of obstacles to national development - in India, caste divisions; in the Arab world, conflicting conceptions of Arab nationalism; in Argentina, an exaggerated particularism stemming in part from Spanish heritage, but also from peculiar Argentine experience. Including discussion of a great variety of nations and problems, ExpectantPeoples inevitably becomes something of a smorgasbord.

As editor, Professor Silvert has the difficult task of pulling these varied pieces together into a coherent structure. He has done so - as well as could conceivably be expected - in a theoretical introduction relating nationalism to development. He sees the key to development in nationalism, which he breaks down into various functional components - juridical nationalism; symbolic nationalism, or patriotism; ideological nationalism (that is, the belief in the state as representing some definable ideal). Perhaps the most important type of nationalism, however, is nationalism as a "social value":

"the loyalty due to fellow citizens and to the mandates of the state, the tacit consent extended to the activities of the state within the national society, and the internalized 'feeling' of national community."

These various components of nationalism are embraced in a single concept (now a Dartmouth litany): "the acceptance of the state as the impersonal and ultimate arbiter of human affairs."

This fundamental loyalty to the state is vital to the development process. Only if such loyalty exists can political leaders make the hard decisions, and the populace accept the sacrifices, which economic development requires. The creative function of nationalism is to secure the necessary loyalty to the state. Professor Silvert is aware that a "sick nationalism" can lead to totalitarianism. But he argues that nationalism becomes truly effective only in a democratic context. Only by granting all groups in the society a sense of participation - in political decision-making, in economic consumption, in social acceptance - can the state command full loyalty.

In countries developing from a "traditional" or tribal state toward modernity, acceptance of the authority of the nation-state requires a change in values. In the ideal-type of the traditional society, the individual adheres to personal leaders rather than accepting the authority of impersonal institutions; he has little or no conception of a shared interest with persons outside his immediate group; and he conceives of truth as absolute and unchanging. To live in a modern society, Professor Silvert contends, the individual must develop a broader social identification, including people outside his class, caste, regional or cultural group; he must conceive of truth as relative (and, one might add, plural); and he must accept the authority of an impersonal national government. The acceptance of these values underlies the "rule of law." When these modern values are weak, as in parts of the United States, social order breaks down. In an underdeveloped country modern values are likely to be still weaker; and society, government, and economy still more disorderly.

The importance of national unity is obvious, Professor Silvert's contribution is in his discussion of the necessary underlying values and of the nature of creative unity. Pointing clearly to the proposition that development requires a fundamental change in social values - and not merely additional capital and technique - Expectant Peoples presents a highly-sophisticated approach to the problems.

Instructor in History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

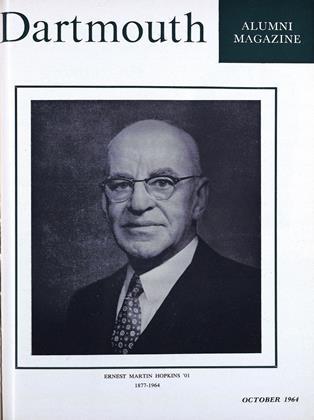

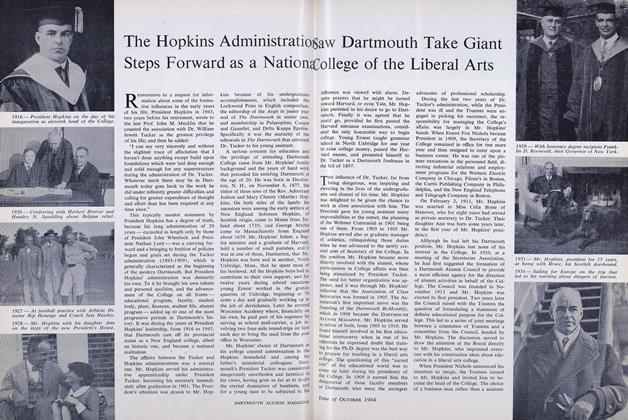

FeatureThe Hopkins Administration Steps Forward as a National

October 1964 -

Feature

FeatureSome Hopkins Views on Higher Education

October 1964 -

Feature

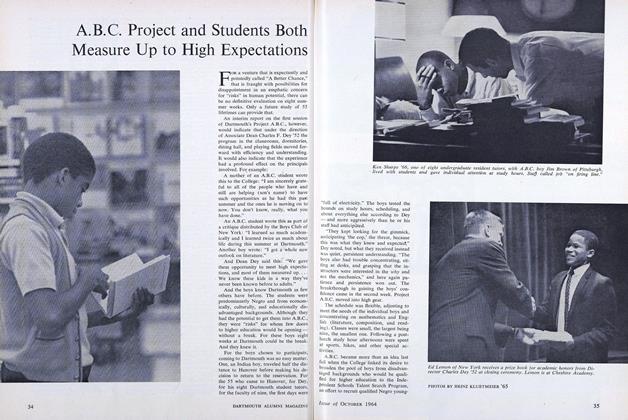

FeatureA.B.C. Project and Students Both Measure Up to High Expectations

October 1964 -

Feature

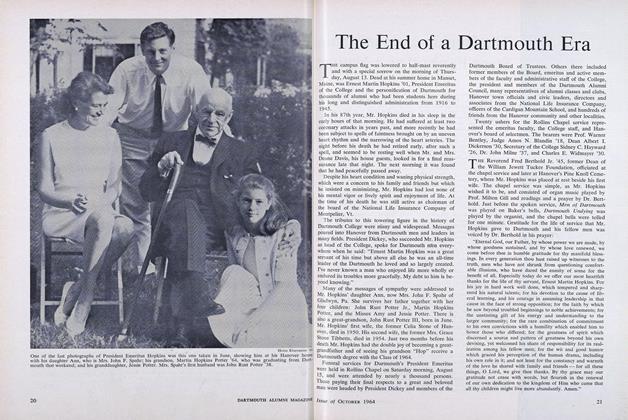

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

October 1964 -

Feature

Feature"This Considerate, Friendly Personality"

October 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

Books

-

Books

BooksGUIDE TO STUDY OF HISTOLOGY AND MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY

APRIL 1932 By C. J. Lyon -

Books

BooksTHURSDAY'S BLADE,

December 1947 By H. M. DARGAN. -

Books

BooksOuting Club Publishes A New Trail Guide

OCTOBER 1968 By JOHN R. PERSON '69 -

Books

BooksGOLDEN TAPESTRY OF CALIFORNIA

February 1938 By Mildred H. Frye -

Books

BooksJOB OPPORTUNITIES FOR YOUNG NEGROES.

FEBRUARY 1970 By RONALD N. TALLEY '69 -

Books

BooksTHINK ON THESE THINGS,

May 1942 By Roy B. Chamberlin