By Page Smith '40. New York: Alfred A.Knopf, Inc., 1964. 261 pp. $4.95.

Page Smith, the distinguished biographer of John Adams and professor of history at UCLA, argues in this book that "history is not a scientific enterprise but a moral one." He surveys the record of historical writing in the West, and then launches into a caustic and hostile attack upon 20th Century "academic history."

Regardless of their stated philosophic premises, he asserts, most historians present the past as though all events were in fact determined and men were without free will. The struggle of men against the elements of necessity in their social situation is, he says, the essential drama of life. If written history obscures this drama, then it is itself lifeless. Worse still, it is dangerous: typical of the consuming passion with which this book is written is Professor Smith's view that failure of written history to retain the sense of that drama might be "the first step on the road to social disintegration."

The author's abhorrence of moral relativism and of determinism is more than matched by his unhappiness with the present state of the historical discipline in America. He finds us guilty of too much fascination with fads and novelty, careless thinking about method, parochialism, and undiscriminating acceptance of specialized monographs which are not history because they are not dramatic. His sweeping indictment would, I think, be more convincing if he proved it by reference to the best of presentday academic historians. Instead, much of his attack is directed rather vaguely against anonymous writers of doctoral dissertations and monographs. Ironically, when he himself treats in detail the various interpreters of the American Revolution he takes a highly determinist view of why they wrote what they did.

One can take little comfort in at least one of the solutions he proposes for the disease that allegedly afflicts us. He seems to believe that "isolated scholars" can combat the insidious influence of academic history by sitting back and somehow absorbing "major readjustments" in historical interpretation. Just how the information and standards for judgment of what is "major" will emerge in this community of contemplative scholars is not quite clear. Nor is it evident who will write the major works which they will absorb.

Equally troubling is Professor Smith's abiding distrust of uncertainty in historical interpretation. (See p. 209.) Does uncertainty harbor some inherent and impalpable evil? Would Professor Smith's great study of John Adams be less important if it happened to introduce uncertainty about the significance of his subject's career? Even if every historian subscribed to the view that history is a moral enterprise, "our greatest reservoir of self-images, ideas, and 'lifestyles,'" would it eliminate multiple-causation theories or introduce absolute certainty?

This brief review can do no more than raise a few of the important issues posed by the author. As a bold, learned, and often infuriating statement of history and its relation to contemporary ethics, this volume - dedicated to Professor Emeritus Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy and a testament to his influence — will reward fully the serious reader.

Assistant Professor of History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

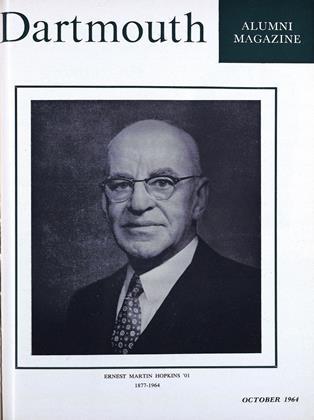

FeatureThe Hopkins Administration Steps Forward as a National

October 1964 -

Feature

FeatureSome Hopkins Views on Higher Education

October 1964 -

Feature

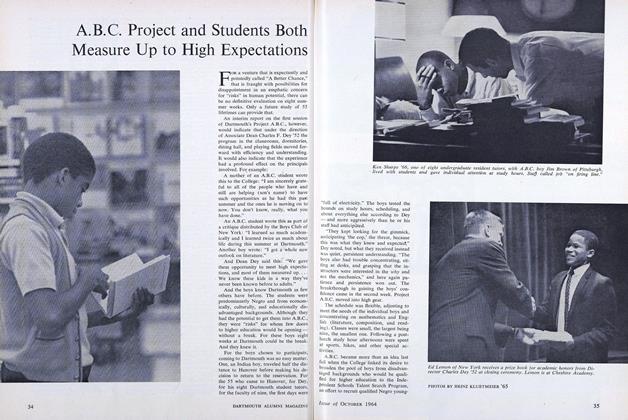

FeatureA.B.C. Project and Students Both Measure Up to High Expectations

October 1964 -

Feature

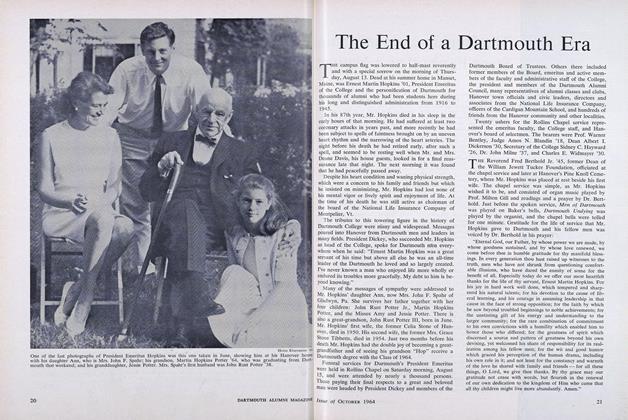

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

October 1964 -

Feature

Feature"This Considerate, Friendly Personality"

October 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

HARRY N. SCHEIBER

Books

-

Books

BooksFLOWERING PLANTS AND VEGETATION. C. J

December 1933 By F. K. Sparrow Jr. -

Books

BooksNOT FOR HYPOCHONDRIACS WE TAKE TO BED

April 1931 By Herbert F. West -

Books

BooksTHE HONEST RAINMAKER.

April 1953 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksCRUSADE

October 1952 By James F. Cusick -

Books

BooksSPEAK TO THE EARTH.

October 1961 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Books

BooksBlack Pawl

February, 1923 By W. B. P.