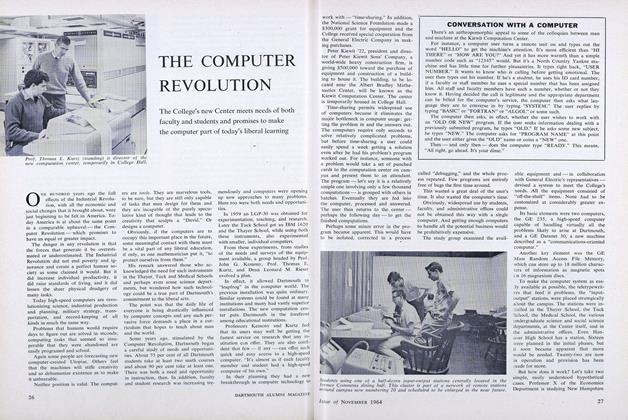

Back in September of 1940 the American Mathematical Society met in Hanover. On the agenda was the first public demonstration of a wondrous new device, the electrical calculator." Accounts of that demonstration provide an interesting commentary on the 24-year development of computation equipment and attitudes toward it.

The "electrical calculator" was a forerunner of today's computers. It was designed by Dr. George Stibitz of the Bell Laboratories, who has come to Dartmouth this fall as research associate in physiology at the Medical School. Wonderful things were claimed for it. It could add, subtract, multiply or divide large, complex numbers, even what mathematicians call imaginary numbers, and return the answer in written form within a short time. Dr. Stibitz demonstrated the device and confounded the assembled mathematicians even further by telling them that the calculator was in New York and that the teletypewriter was connected to it by telegraph cable.

To test it one mathematician asked that this problem be computed: .56785432, minus i12564532 (i for imaginary) multiplied by .45632450 plus i45367899. In 40 seconds the answer came back: plus .31612847 or plus .20028853.

Prof. Thomas E. Kurtz, director of the Kiewit Computation Center, was asked recently to verify this problem. Yes, Stibitz and his calculator were right. The time recorded by the 1964 machine was 0 seconds. Professor Kurtz explained that, no, the machine hadn't as yet revised our concepts of time. It was just that any problem requiring less than half a second registered as 0.

The contemporary accounts also showed traces of skepticism. The Associated Press, for instance, inserted such words as "reputedly can solve," "he declared," and so forth. It was almost as if the reporters suspected that a little man with a large slide rule or pencil was in the New York laboratories.

The old New York Sun said: "No attempt has been made to explore the general commercial possibilities of the calculating machine and the Bell Laboratories have no plan to spread its use beyond their own needs, which are specific. They have not the remotest idea that with their machine they ever will be able to perform a service for any outside industry and they do not foresee the time when Johnny, aged 12, will be able to pick up his telephone receiver and ask the operator for the answer to seven times nine."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePrelude to a Third Century

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureTHE COMPUTER REVOLUTION

November 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

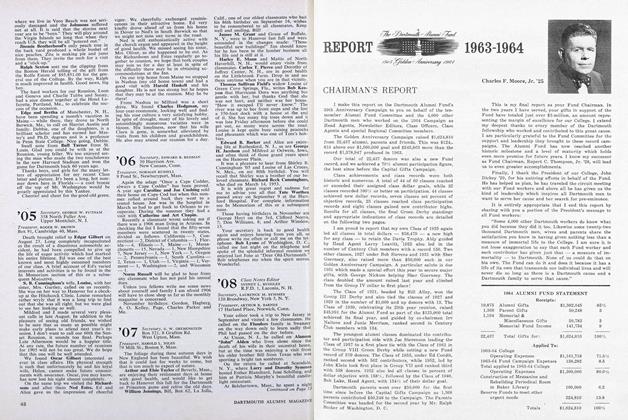

FeatureThe Darthmouth Alumni Fund REPORT 1963-1964 1915 Golden Anniversary 1964

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureREPORT CARD

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

November 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65

Article

-

Article

ArticleFreshman Baseball

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleTuck-Thayer Changes

December 1959 -

Article

ArticleJust One Question

May/June 2002 -

Article

ArticleRoller Skates Take to the Woods

MARCH 1994 By Ericka Houck '93 -

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AND CHOATE IN COLLEGE

APRIL, 1927 By Herbert Darling Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleA Free Man Is Answerable

November 1951 By President Dickey