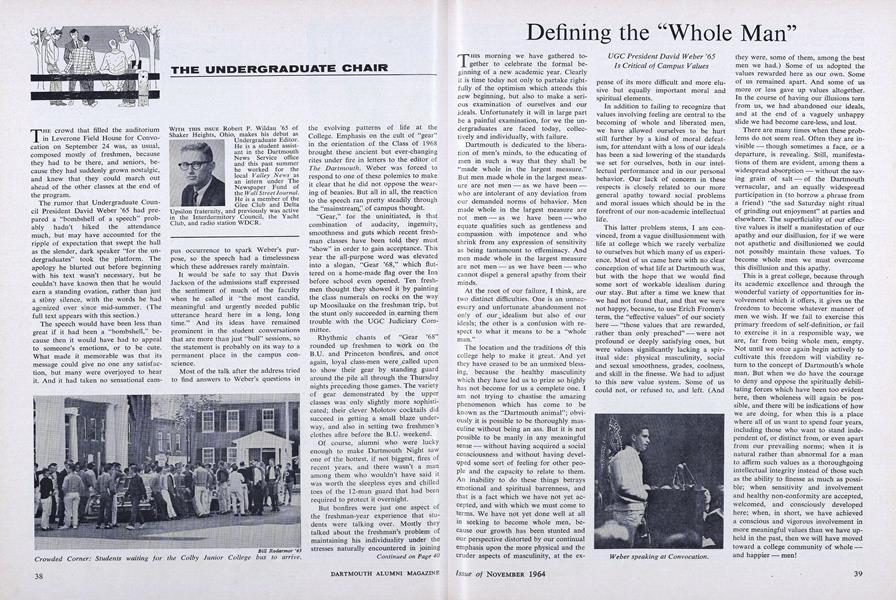

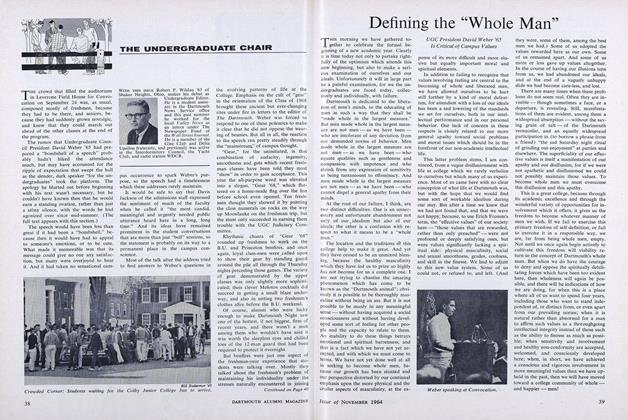

UGC President David Weber '65Is Critical of Campus Values

THIS morning we have gathered together to celebrate the formal beginning of a new academic year. Clearly it is time today not only to partake rightfully of the optimism which attends this new beginning, but also to make a serious examination of ourselves and our ideals. Unfortunately it will in large part be a painful examination, for we the undergraduates are faced today, collectively and individually, with failure.

Dartmouth is dedicated to the liberation of men's minds, to the educating of men in such a way that they shall be "made whole in the largest measure." But men made whole in the largest measure are not men - as we have been - who are intolerant of any deviation from our demanded norms of behavior. Men made whole in the largest measure are not men — as we have been - who equate qualities such as gentleness and compassion with impotence and who shrink from any expression of sensitivity as being tantamount to effeminacy. And men made whole in the largest measure are not men - as we have been - who cannot dispel a general apathy from their minds.

At the root of our failure, I think, are two distinct difficulties. One is an unnecessary and unfortunate abandonment not only of our , idealism but also of our ideals; the other is a confusion with respect to what it means to be a "whole man."

The location and the traditions of this college help to make it great. And yet they have ceased to be an unmixed blessing, because the healthy masculinity which they have led us to prize so highly has not become for us a complete one. I am not trying to chastise the amazing phenomenon which has come to be known as the "Dartmouth animal"; obviously it is possible to be thoroughly masculine without being an ass. But it is not possible to be manly in any meaningful sense - without having acquired a social consciousness and without having developed some sort of feeling for other people and the capacity to relate to them. An inability to do these things betrays emotional and spiritual barrenness, and that is a fact which we have not yet accepted, and with which we must come to terms. We have not yet done well at all in seeking to become whole men, because our growth has been stunted and our perspective distorted by our continual emphasis upon the more physical and the cruder aspects of masculinity, at the expense of its more difficult and more elusive but equally important moral and spiritual elements.

In addition to failing to recognize that values involving feeling are central to the becoming of whole and liberated men, we have allowed ourselves to be hurt still further by a kind of moral defeatism, for attendant with a loss of our ideals has been a sad lowering of the standards we set for ourselves, both in our intellectual performance and in our personal behavior. Our lack of concern in these respects is closely related to our more general apathy toward social problems and moral issues which should be in the forefront of our non-academic intellectual life.

This latter problem stems, I am convinced, from a vague disillusionment with life at college which we rarely verbalize to ourselves but which many of us experience. Most of us came here with no clear conception of what life at Dartmouth was, but with the hope that we would find some sort of workable idealism during our stay. But after a time we knew that we had not found that, and that we were not happy, because, to use Erich Fromm's term, the "effective values" of our society here - "those values that are rewarded, rather than only preached" - were not profound or deeply satisfying ones, but were values significantly lacking a spiritual side: physical masculinity, social and sexual smoothness, grades, coolness, and skill in the finesse. We had to adjust to this new value system. Some of us could not, or refused to, and left. (And they were, some of them, among the best men we had.) Some of us adopted the values rewarded here as our own. Some of us remained apart. And some of us more or less gave up values altogether. In the course of having our illusions torn from us, we had abandoned our ideals, and at the end of a vaguely unhappy slide we had become care-less, and lost.

There are many times when these problems do not seem real. Often they are invisible - though sometimes a face, or a departure, is revealing. Still, manifestations of them are evident, among them a widespread absorption - without the saving grain of salt — of the Dartmouth vernacular, and an equally widespread participation in (to borrow a phrase from a friend) "the sad Saturday night ritual of grinding out enjoyment" at parties and elsewhere. The superficiality of our effective values is itself a manifestation of our apathy and our disillusion, for if we were not apathetic and disillusioned we could not possibly maintain those values. To become whole men we must overcome this disillusion and this apathy.

This is a great college, because through its academic excellence and through the wonderful variety of opportunities for involvement which it offers, it gives us the freedom to become whatever manner of men we wish. If we fail to exercise this primary freedom of self-definition, or fail to exercise it in a responsible way, we are, far from being whole men, empty. Not until we once again begin actively to cultivate this freedom will viability return to the concept of Dartmouth's whole man. But when we do have the courage to deny and oppose the spiritually debilitating forces which have been too evident here, then wholeness will again be possible, and there will be indications of how we are doing, for when this is a place where all of us want to spend four years, including those who want to stand independent of, or distinct from, or even apart from our prevailing norms; when it is natural rather than abnormal for a man to affirm such values as a thoroughgoing intellectual integrity instead of those such as the ability to finesse as much as possible; when sensitivity and involvement and healthy non-conformity are accepted, welcomed, and consciously developed here; when, in short, we have achieved

a conscious and vigorous involvement in more meaningful values than we have upheld in the past, then we will have moved toward a college community of whole - and happier - men!

Weber speaking at Convocation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePrelude to a Third Century

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureTHE COMPUTER REVOLUTION

November 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe Darthmouth Alumni Fund REPORT 1963-1964 1915 Golden Anniversary 1964

November 1964 -

Feature

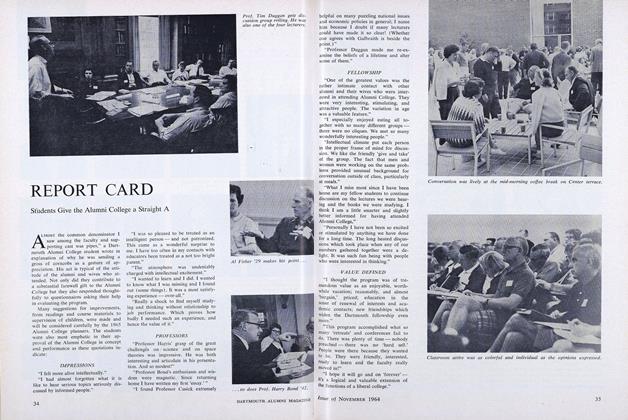

FeatureREPORT CARD

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

November 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65

Article

-

Article

ArticleA PROPOSAL FOR LEADERSHIP

November 1932 -

Article

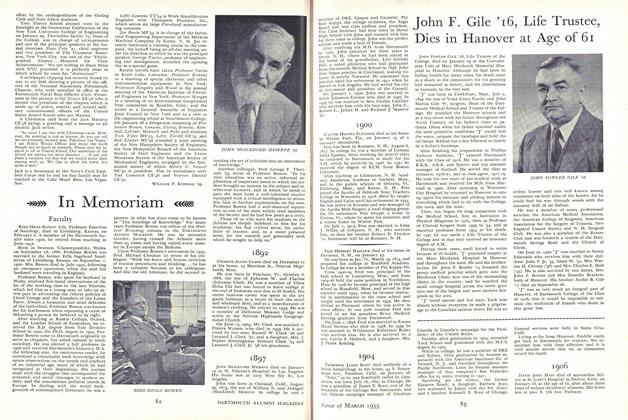

ArticleJohn F. Gile '16, Life Trustee, Dies in Hanover at Age of 61

March 1955 -

Article

ArticleRecent Gifts and Bequests to College Illustrate a Wide Range of Support

JANUARY 1967 -

Article

ArticleWinter Sports Need Transfusion

FEBRUARY 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleSTREETER HALL

May 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleConnecticut

June 1938 By Mansfield D. Sprague '33.