Edited by President John Sloan Dickey'29. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hail,Inc. 1964. 184 pp. $3.95 ($1.95 paperback).

Canada, now a nation with nearly 20,000,000 citizens, plays a crucial role in the security system of the Western world, and in many ways it is the United States' most intimate and important ally. Yet American ignorance of our northern partner and neighbor is almost limitless, and there is a pressing need for a greater understanding of the complexities of Canadian-American relationships and of the growingly complex society of Canada itself.

The United States and Canada, in which President Dickey has assembled a distinguished group of Canadian and American scholars under the auspices of the American Assembly, contributes significantly to the filling of this void. Each of the six essays which make up the body of the book examines facts, issues, and viewpoints which are essential to an analysis of the network which joins the two countries and of the short circuits that all too frequently occur within that network. What the book as a whole succeeds in doing is to bring into sharp relief a set of intricate political, economic, and cultural problems that tax the skills of policy-makers for both countries and offer exciting research possibilities for scholars.

What are some of the "hard issues," as James Eayrs calls them, that beset Canadian-American relations? One of the hardest involves defense and defense planning. Despite the unprecedented meshing of American and Canadian chains of command in the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD), there are significant differences of approach to the defense problem. This is illustrated by the long delayed negotiations concerning Canadian acquisition of nuclear warheads for weapons systems which the United States and Canada Jointly maintain. More than five years elapsed before Canada reluctantly agreed in 'ate 1963 to harbor atomic weapons on its soil. The Canadian desire to manufacture some of its own weapons systems, its concern for a fair share of defense production contracts in joint undertakings, and the failure of both sides to coordinate the production of such strategic raw materials as uranium and oil are examples of other "hard issues" in the area of defense.

Professor Eayrs makes it clear, however, that most of these issues are affected by a powerful current in Canadian public opinion which fears and resents Canada's terrible vulnerability in its position athwart the most likely route of two way missile exchange. Still more vulnerable Americans should remember that their safety is at least a product of their own government's policies, while Canada's fate is bound to the decisions of a government in Washington which, however friendly, is nonetheless foreign. The easing of this Canadian resentment and the concrete defense issues it affects can only be brought about by unremitting efforts on the part of the United States to treat Canada as a full-fledged partner in the business of protecting North America.

Divergent foreign trade policies, especially with the Iron Curtain countries, have been another source of Canadian-American friction. As John Holmes notes, "Canada, which is much more dependent on trade than is the United States, is much more reluctant to interrupt commerce for political reasons." Trade with Communist China, Cuba, and Russia have constituted specific points of disagreement. But since the United States followed Canada's lead last year in selling huge amounts of surplus wheat to the Soviet Union and in the light of the increasing split in the communist camp, American policy is in the future likely to be more tolerant of pragmatic attitudes toward the interrelationship of international politics and international trade.

The problem of trade leads into the whole subgovernmental area of international relations, a particularly fascinating and complicated one in the case of the two North American neighbors. In 1961, according to the Dominion Bureau of Statistics, United States residents controlled 45 percent of all Canadian manufacturing, 60 percent of all Canadian petroleum and natural gas production, and 52 percent of all Canadian mining and smelting. These are formidable portions of a country's resources and production to reside in the hands of foreigners, and they constitute an understandable Canadian concern. Nonetheless, American private investment has been one of the chief sources of Canadian economic expansion and prosperity, and it behooves our Canadian neighbors to recognize their benefits as well as their possible disadvantages in case of an American recession.

Canadian and American labor are as interlocked as Canadian and American capital. More than 70 percent of all Canadian trade union members belong to unions whose headquarters are in the United States. This situation can lead to such unhappy consequences as the Great Lakes shipping dispute of last year in which the parent American organization of the Seafarers' International Union challenged the Canadian government's decision to place the Canadian SIU under governmental trusteeship because of the Canadian affiliate's strong-arm methods on the docks. Governmental and public indignation in Canada at this interference in Canadian internal affairs was aggravated further by the fact that the head of the Canadian affiliate is himself an American citizen and is at present a fugitive from justice after having been convicted in a Montreal court of conspiracy and assault. This intermeshing of governmental and subgovernmental relations across the border calls for a high degree of skill and vigilance in diplomacy and more public awareness in the United States of the trans-border complex of problems.

Canada's number one foreign problem, as Mason Wade stresses, is the United States. But now Canada is beset by a domestic issue which overshadows in importance all of her external relations. The tensions between French-speaking and English-speaking Canadians have risen to such a point that the very survival of Canadian Confederation is at stake. Professor Eayrs puts the problem most bluntly when he says that "In Canada, the critical issue is whether all Canadians, and particularly French-speaking Canadians, consider their country worth keeping." While most of the essays in TheUnited States and Canada refer to this major crisis, the American student needs to know much more about its nature and prospects in order to assess its possibly grave impact on United States-Canadian relations. Canada is going through perhaps the most difficult period in all its history, and it needs now as never before a thoughtful and sympathetic American neighbor. We should recognize, among other things, that there is a curious parallel between Canadian attitudes toward the United States, on the one hand, and French-Canadian attitudes toward their English-speaking compatriots on the other. Just as Canada demands respect from and independence of the United States within the North American partnership, so French- Canadians demand respect and autonomy within Canada. All three members of this North American triangle are going to have to devote increasing attention to the problem of finding unity within diversity.

America and Canada each has the task of healing grave internal dissensions. Jointly, they have the task of demonstrating that stronger and weaker partners in international politics can live together side by side in independence, cooperation and friendship. Greater mutual understanding is essential to the accomplishment of both these tasks, and we should be grateful to the editor and authors of The United States andCanada for their valuable contribution to this end.

Professor of Government

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePrelude to a Third Century

November 1964 -

Feature

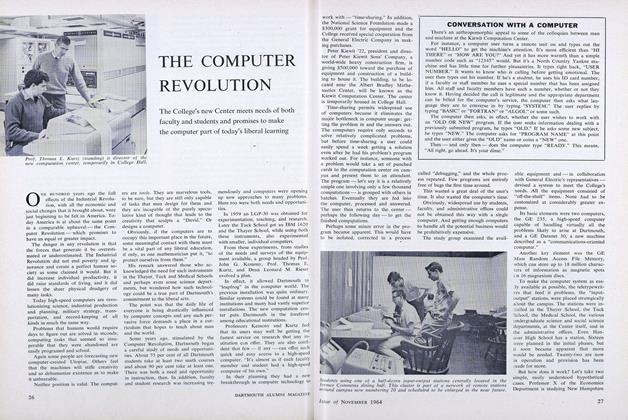

FeatureTHE COMPUTER REVOLUTION

November 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

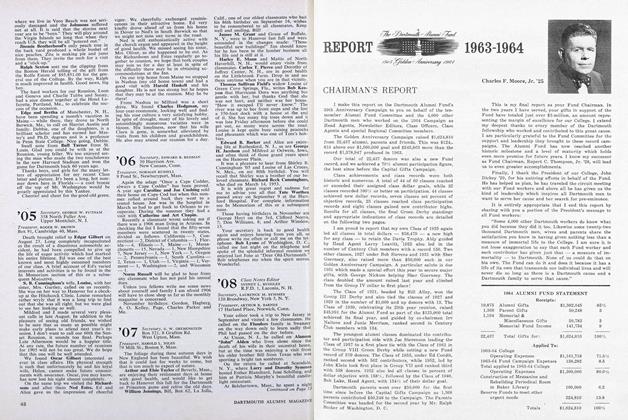

FeatureThe Darthmouth Alumni Fund REPORT 1963-1964 1915 Golden Anniversary 1964

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureREPORT CARD

November 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

November 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65

RICHARD W. STERLING

-

Books

BooksTHE CASE FOR PEACE.

January 1956 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Books

BooksMINNESOTA AND THE MANIFEST DESTINY OF THE CANADIAN NORTHWEST.

APRIL 1966 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Books

BooksPROSPECTS FOR PEACEKEEPING.

MARCH 1968 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Books

BooksSOVIET-MIDDLE EAST RELATIONS (SOVIET-THIRD WORLD RELATIONS. Vol. I — A SURVEY IN THREE VOLUMES).

February 1974 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

DECEMBER • 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING

Books

-

Books

BooksCHALLENGE AND PERSPECTIVE IN HIGHER EDUCATION.

MAY 1971 By ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Books

BooksA Higher Law

December 1978 By CHARLES T. DUNCAN '46 -

Books

BooksWHO'S ZOO IN THE GARDEN

June 1941 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksTHE ORAL NATURE OF THE HOMERIC SIMILE.

October 1974 By RICHMOND LATTIMORE'26 -

Books

BooksA UNIFIED FIELD THEORY.

JULY 1965 By SANBORN C. BROWN '35 -

Books

BooksA HISTORY OF AMERICAN ECONOMIC LIFE

October 1951 By W. R. Waterman