Wayne G. Broehl, Jr. Cambridge, Mass.:Harvard University Press, 1964. 409 pp.$8.95.

The Molly Maguire murders occurred in the early 1870's in the most southern of the Pennsylvania anthracite fields. Eventually the perpetrators of these killings were uncovered by an operative, James McParlan, from the Pinkerton agency who wormed his way into the inner circle of the murderers by posing as a fugitive from justice and by his lavish habit of standing drinks on an expense account in the taverns of this miserable region. Largely on the evidence McParlan collected, Pennsylvania justice hung twenty "Mollies."

Though the story has often been told, Mr. Broehl has had the scholarly imagination and the luck to provide new evidence. He traces the origin, the methods, and the name of the Mollies to a background in Ireland where rack-rented tenants had resorted to terroristic secret societies in their age-long struggle against absentee landlords and English domination. On this side of the water Broehl secured access to McParlan's letters in the files of the Pinkerton agency and to the records of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad which employed McParlan and other Pinkertons to track down the violence in the coal regions.

Forecasting is perilous. But it is doubtful if any later writer will be able to add to the extensiveness and thoroughness of the research shown by this volume.

Historians have used the Molly Maguires for many purposes. Some have introduced the episode to furnish excitement to a narrative otherwise dully written. Others have used it to illustrate the propensity of labor organizations to violence or the malevolence of employers in crushing labor unions. Broehl doesn't subscribe to either extreme. Instead he fittingly traces the evolution of coal mining from individualistic competition to monopoly organization, particularly under the leadership of F. B. Gowen, the powerful leader of the Philadelphia and Reading; the decline of coal prices and the efforts of workers and management to stabilize them; the ethnic tensions between bosses who were English and Welsh and workers who were Irish; the Protestant-Catholic antagonism; the restiveness of a community at the prevalence of violence; a restiveness which erupted into vigilantes. In the end I conclude that this episode is not as appropriately assigned to the category of labor-capital antagonism as to the strain of violence which, we are all too aware, underlies American culture.

The "King of the Mollies" proved to be not a labor organizer but a tavern keeper. Anthracite mining, entirely aside from human depravity, operated in a dismal business and ecological setting which bred feuds and frustrations. If Mr. Broehl seems to shove aside socio-economic considerations, it is because the adventure of this detective exploit has caught him, as it has his predecessors, in its toils. The deftness with which he untangles this complicated narrative of comings and goings, crises, crimes, and retribution is exceptional. His last sentence reads: "It was quite a story." A reviewer, unhampered by an author's proprieties, can honestly add: No one has told it anywhere near so well.

Professor Emeritus of History atBowdoin College and now a residentof Thetford Center, Vt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureVANISHING ABSOLUTES

December 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOur Battle To Reform The Education of Teachers

December 1964 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40 -

Feature

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

December 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

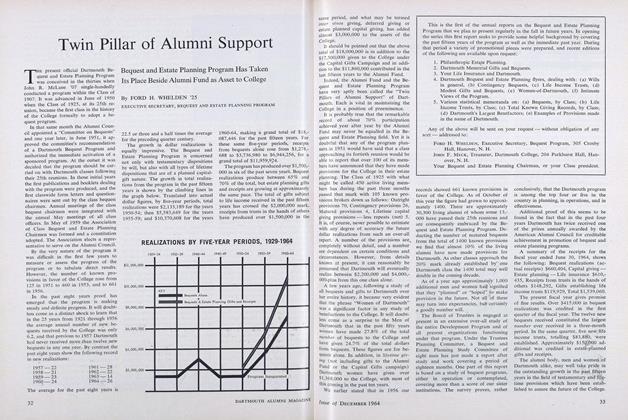

FeatureTwin Pillar of Alumni Support

December 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

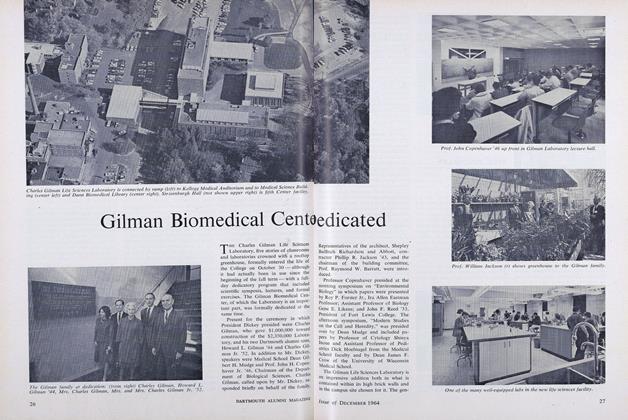

FeatureGilman Biomedical Centedicated

December 1964 -

Article

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

December 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65

EDWARD C. KIRKLAND '16

Books

-

Books

Books"The Fair State of Return in Public Utility Regulation"

APRIL 1932 -

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

December 1946 -

Books

BooksLake Unlocked

SEPT. 1977 By CHARLES T. MORRISSEY '56 -

Books

BooksGRANITE LAUGHTER AND MARBLE TEARS

December 1938 By Harold G. Rugg '06. -

Books

BooksALBERT INSKIP DICKERSON: SELECTED WRITINGS

November 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R.