By Prof. WayneG. Broehl Jr. (Tuck School). Washington:National Planning Association, 1968. 312pp. Paperback $3. Cloth $6.50.

When the Rockefellers recently bought the Woodstock (Vt.) Inn, natives were naturally curious and apprehensive. When the family goes into the hotel business, the act can be the beginning of a long and unrevealed commitment. Thus when Nelson Rockefeller with others built and operated the Avila Hotel in Caracas in the nineteen- forties, it was the first step to the incorporation in 1946 in New York State of the International Basic Economy Corporation whose purpose was to bring American technical aid, management and business skills, and capital to the elevation of living standards and welfare in countries less well developed. While the means were humanely formulated and sensitively applied, the overall setting was to be a private and profitable enterprise. Mr. Broehl's book is an appraisal of this complicated undertaking. The customary foundation support financed in part his research.

The impression is of a hurdle race in a labyrinth. When supermarkets were introduced to Caracas, customers were uncertain how to get through turnstiles and cook with cake mixes. When IBEC decided to manufacture powdered milk with a taste as near "natural" as possible, Venezuelans developed a preference for a product with a "burnt" taste because they were used to it. When it sought to raise the protein level of populations by introducing the American system of manufacturing chickens, they were entangled in the choices between egg production, fertile and infertile, breeder and broiler chicks, and profits from the feed business. Broehl has to use a chart to make the procedure understandable.

In India the company coped with dietary taboos through "vegetarian eggs" produced by the segregation of chicken sexes; in Argentina a partly educated veterinarian was on the verge of ordering the destruction of a huge flock of birds by mistaking the antibodies against Newcastle disease in a vaccine for the infective agent. The company escaped loss by calling veterinarians, not the Marines, from the United States. Some of this is "quaint," some ludicrous — all of it real. It gives substance to the narrative. More theoretical is the discussion of the inflationary epidemic in Latin America where the activities of IBEC have been most varied and the speculation as to what constitutes "tolerable inflation."

The volume sounds like a position paper which a board of directors or administrators could read with profit. Mr. Broehl is too self-effacing to discuss publicly the worth of the report to himself as a scholar. Set in the variety of his writing, it can be justified as developing a flexibility of interests and means of communications. But every discipline gains from the continuous exercise of its own insights and its own literary style. This snowball effect, experience demonstrates, is particularly characteristic in the study of the humanities and in social topics. The answer to the question raised in this paragraph is more than personal; it is institutional.

Author of many books, Litt.D. from Dartmouth and Princeton, Mr. Kirkland was amember of the faculty of Bowdoin College,1930-1955.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

July 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68 -

Feature

Feature"People as Well as Things"

July 1968 By HARVEY P. HOOD '18 -

Feature

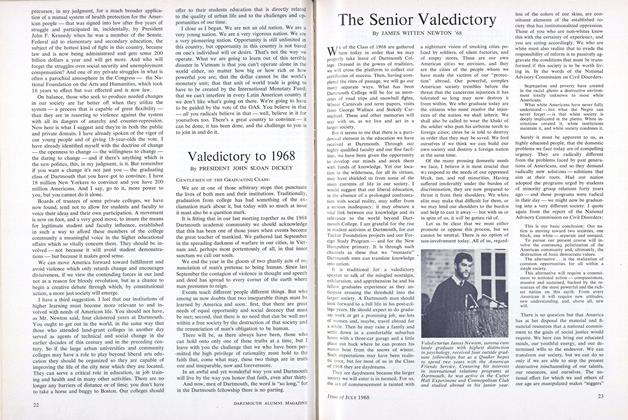

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1968 By JAMES WITTEN NEWTON '68 -

Feature

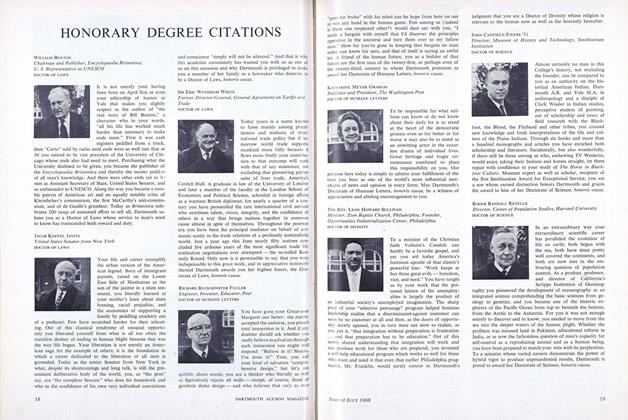

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1968 -

Feature

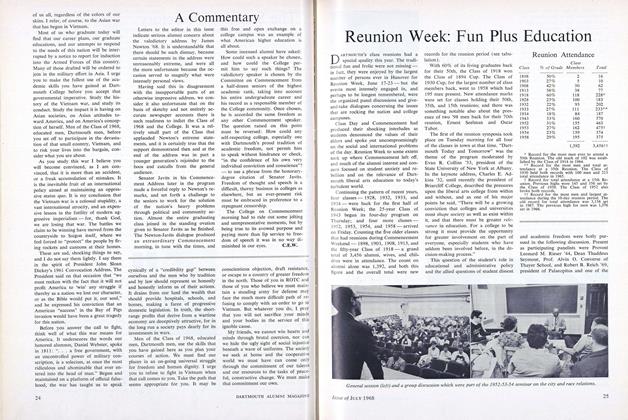

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

July 1968 -

Feature

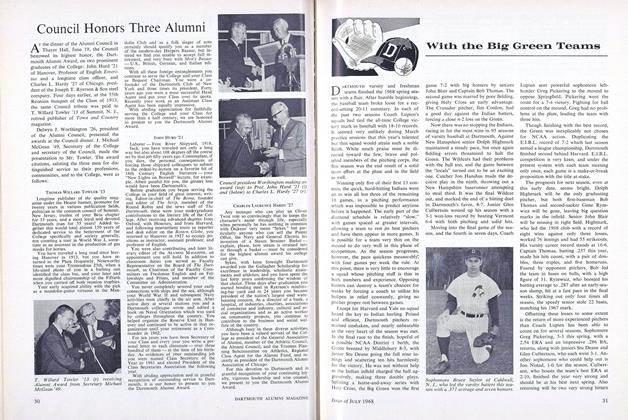

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

July 1968

EDWARD C. KIRKLAND '16

Books

-

Books

BooksProfessor J. B. Stearns is the author of Epicurus and Lucretius

April 1936 -

Books

BooksHunger: The Biology and Politics of Starvation

July/August 2011 -

Books

BooksWAR AND THE POET

January 1946 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

BooksSOFT MONEY

October 1939 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksFAT MUTTON AND LIBERTY OF CONSCIENCE: SOCIETY IN RHODE ISLAND, 1636-1690.

February 1975 By LOUISE RIEGEL -

Books

BooksMEXICO AND ITS HERITAGE

MAY 1930 By Mcquilken De Grange