By KarlU. Smith and William M. Smith A.M. '63.Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1962. 341pp. $8.00.

This is a book about perceptual-motor integration. "We are studying perception and motion not as two separate forms of adaptation, but as one mechanism, adapting the movements of the body to the gravitational and three-dimensional characteristics of space." It is organized around the results of experiments dealing with spatially-displaced visual fields, and begins with the conviction that "from the very first, the motions of the fetal body are space-structured."

Thus the organization of motion in the animal system is considered to be genetically determined and only incidentally modified by specific learning. A critical evaluation of earlier studies of displaced vision leads to the rejection of a basic assumption, "that the conditions and results of experimentally displaced vision duplicate the critical features of normal perceptual development," and the authors proceed to reinterpret both these earlier studies and their own extensive experimentations in terms of a neurogeometric theory of motion. The primary assumption of this theory is "that the internuncial neurons of the central nervous system are organized so as to detect differences in stimulation between two points on the body."

A Type I or intra-receptor detector operates if the two points are on the same receptor; a Type II or inter-receptor operates if the points are in different receptor systems; and a Type III or efferent-afferent detector operates when one point is associated with an effector and the other with a receptor. When there is a difference in excitation between the two inputs the neurogeometric detector is excited. When there is no difference, there is no response.

Another basic proposition is that the temporal organization of motion depends on the continuous barrage of sensory feedback signals ... which compare a motion and its effects with stimulus patterns of the environment." Motion itself is described as having three components - postural (controlled by gravitational stimulation), transport (controlled by bilateral differences in stimulation), and manipulative (controlled by the spatial properties of hard space) and the neurogeometric detectors are conceived as "heritable anatomical units" to account for the genetic determination of behavior.

The reviewer is impressed with the parsimony effected by this theoretical orientation but is unable to evaluate it from a neuro-physiological standpoint. Where the theory is applied to the development of speech patterns it has decided advantages over association theories which have nothing to say about mechanisms, and more generally, it has the merit of directing perceptual research towards fruitful conclusions; namely, the discovery that such detectors do not exist or that they do. Finally, quite apart from the theory, this book serves an important function through the introduction of new and much improved optical and television techniques for the study of displaced vision.

Assistant Professor of Psychology

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

March 1964 By THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50 -

Feature

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

March 1964 -

Feature

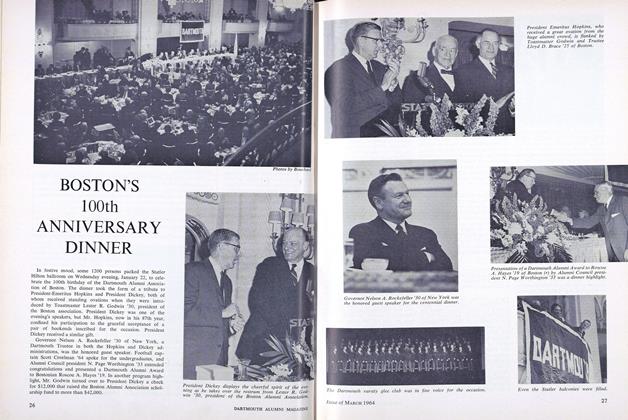

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

March 1964 -

Article

ArticleA graduate of 1804 who stood up for an American Culture

March 1964 By BEN HARRIS McCLARY -

Article

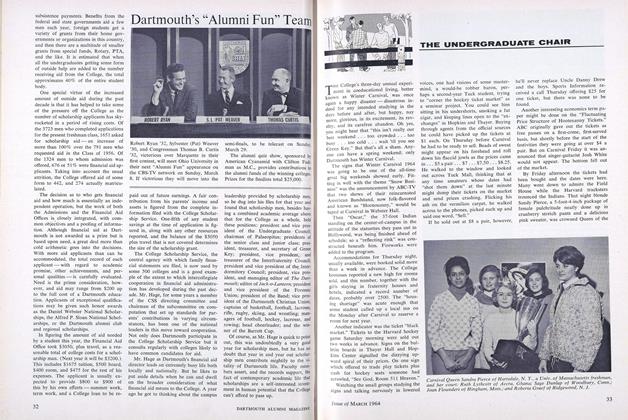

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

March 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

Books

-

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

DECEMBER 1967 -

Books

BooksWHO'S WHO AMONG THE MICROBES

MARCH 1930 By A. H. Chivers -

Books

BooksJAMES WILSON: FOUNDING FATHER, 1742-1798.

July 1956 By A. L. DEMAREE -

Books

BooksALP.

MAY 1970 By JOHN J. KANE -

Books

BooksTHE FUTURE LIKE A BRIDE.

July 1958 By PAUL LAUTER -

Books

Books100 AMERICAN POEMS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY.

NOVEMBER 1966 By THOMAS CARNICELLI