reinstated with introduction and notes byWing-tsit Chan. New York: St. John'sUniversity Press, 1963. 193 pp. $3.50.

Over the past few years so many popular books on the topic of Zen Buddhism have appeared that any new entry into the field is liable to be viewed with suspicion and reserve. It is therefore especially delightful to find a new and readily available offering which is scholarly, readable, and a significant contribution to the literature on Zen.

The importance of the T'an-ching of Platform Scripture for a proper understanding of Zen Buddhism or more properly Ch'an Buddhism, its Chinese prototype, cannot be overestimated. The usual disregard of the Ch'an Buddhists and their frequent irreverence toward any kind of verbal or written exposition has been widely publicized. Perhaps less well known is the respect paid to the great patriarchs of the sect and the especial esteem tended the sixth patriarch, the Chinese monk Hui neng (A.D. 638-713), whose sermon provides the body of the Platform Scripture which has since become a major text of one branch of the Ch'an sect.

Professor Chan's work is the first translation based entirely on the earliest known copy of the Platform Scripture discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in the caves of Tun Huang at the turn of the century. Professor Chan has not limited himself exclusively to the Stein manuscript, but has supplemented a study of that manuscript with other copies of later dates and one valuable feature of the book is the frequent reference to other editions and comment on later interpolations and errors of interpolations.

The book falls into two parts: an introduction which is in reality a short essay on Zen with specific reference to Hui neng followed by the scripture itself. Both sections are well documented by copies and brief informative notes. While the introduction would certainly be of most value to the general reader, even those who are unfamiliar with Ch'an Buddhism will find much that is useful throughout. The tendency in most books dealing with the topic is to treat Zen as a homogenous phenomenon, entirely devoid of any sectarian differences. Professor Chan's remarks on the southern school of Hui neng and the northern school (founded by a contemporary rival monk) bring to life the dynamic controversy of 7th Century China and the emergence of the southern school as eventual victor. That southern school has best captured the imagination of the modern Western reader. A careful reading of the introduction allows one to follow between the lines the subtle references to these internecine differences in the text itself.

Professor Chan's translation of the text is readable and those who wish to question its accuracy may make reference to the Chinese text which appears facing the translation or to the many notes and references in the supplement. While it is always tempting to lift a favorite quotation out of the text, especially with Zen works, I will forego the temptation and suggest that the reader treat the work as a whole. The single quotation is always attractive and lends itself to the creation of total aphorisms but is pale next to the discursive power of the sermon. In fact much of the obscurity and exotic sentimentality which has grown up around this aspect of Buddhism must certainly vanish before the power of Hui neng's sermon so clearly and vividly presented by Professor Chan.

Assistant Professor of Art

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

March 1964 By THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50 -

Feature

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

March 1964 -

Feature

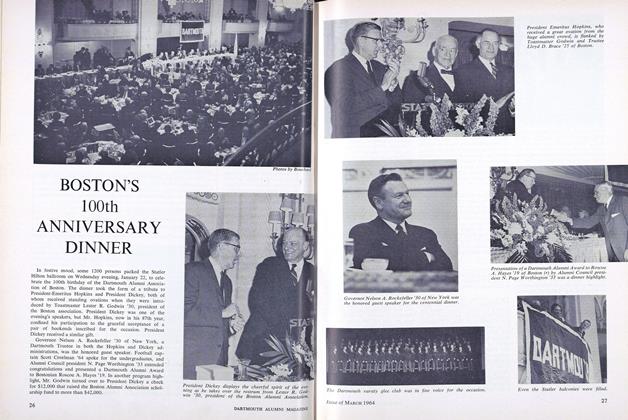

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

March 1964 -

Article

ArticleA graduate of 1804 who stood up for an American Culture

March 1964 By BEN HARRIS McCLARY -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

March 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

ROBERT J. POOR

Books

-

Books

Books"The Pardoning of Prisoners by Pilate"

March 1917 -

Books

BooksMathematical Theory of Life Insurance

April, 1925 -

Books

BooksELECTRICITY AND MAGNETISM

March 1933 By C. A. P -

Books

BooksOTHER LOYALTIES, A POLITICS OF PERSONALITY.

MARCH 1969 By GENE S. CESARI '52 -

Books

BooksNATURE LOVER'S TREASURY.

May 1948 By Herbert F.West '22. -

Books

BooksDEMOCRACY AND THE PUBLIC SERVICE

JANUARY 1969 By NELSON LEE SMITH '21