By Edward B. Lockett '28. New York, Exposition Press, 1964. 196 pp. $4.00.

Edward B. Lockett in this book aims at discouraging Puerto Rican migration to the United States mainland. The Puerto Ricans' presence increases the tax burden of mainlanders, particularly in New York, as education, health and welfare facilities must be expanded and adjusted to meet their needs. Further, in his opinion, Puerto Ricans are "inassimilable" because they are "darkskinned," speak Spanish, and are "antagonistic ... toward the United States" and its culture.

Mr. Lockett wistfully, and at some length, describes the British decision to restrict immigration from Jamaica, but concludes that the United States could not similarly legislate the exclusion of Puerto Ricans. They are, after all, United States citizens.

As exclusion cannot be legislated, Mr. Lockett suggests an alternative method of curtailing migration. His proposal - rather indelicately called "Operation Upgrade" - consists of: a public works program on the island, which by providing Puerto Ricans with subsistence wages, might deter them from migrating; "an educational and training operation to upgrade Puerto Ricans' work capabilities"; and a program to "orient islanders thoroughly to mainland climate rigors, customs and living habits, including recognized prevalent economic and social discrimination."

Except for the intent of this last clause; the program would appear praiseworthy, and entirely in keeping with the President's "war on poverty." One only wishes the program had been proposed in a spirit of genuine concern for the Puerto Rican. Unfortunately, the book does not convey this spirit. If Mr. Lockett were really concerned about the Puerto Rican, he might have described in detail how "Operation Upgrade" would be carried out. This he does not do. After dropping the suggestion, he washes his hands.

Nor, in fact, does he really discuss the plight of Puerto Ricans in New York or the Puerto Ricans' impact on the city's services. Nowhere is there convincing evidence that the Puerto Ricans are the drain on New York which Mr. Lockett suggests. He himself admits Puerto Ricans are now the backbone of the restaurant-hotel and garment industries.

Other propositions in the book are open to question. Mr. Lockett exaggerates the cultural differences between island and mainland. The differences, it is true, were once great. But now bilingual, bicultural communities - complete with newspapers, radio stations, and political leaders - exist in both New York and San Juan. To suggest, as the book does, that cultural characteristics are "immutable" is mistaken.

The extent to which Puerto Ricans have integrated in New York is suggested by their political activities of the past four years. Mr. Lockett notes their "indifferent voting at the municipal level" before 1960 - without mentioning Tammany's efforts to keep the Puerto Rican disfranchised. It is a tribute to the community in East Harlem that in 1960 enough Puerto Ricans passed English language tests to elect a reform assemblyman against the massed power of Tam- many Hall. The fact that Puerto Ricans have joined Negro Americans in demonstrations for better schools also indicates that the social integration needed for civic awakening has begun to occur.

There are bits of fantasy m this book - most notably ,in the chapter which suggests that Puerto Ricans might serve as a base for Communist infiltration of the United States. Elsewhere, however, the tone is sweetly reasonable - though the book's emphasis on the darkness of Puerto Rican skins reflects attitudes which are less than admirable.

Instructor in History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Big Ferment in Engineering Education

June 1964 By DAVID ALLISON, -

Feature

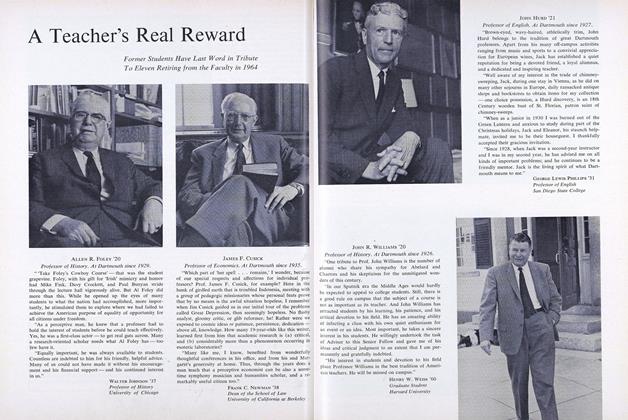

FeatureA Teacher's Real Reward

June 1964 -

Feature

FeatureSports for the Multitude

June 1964 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

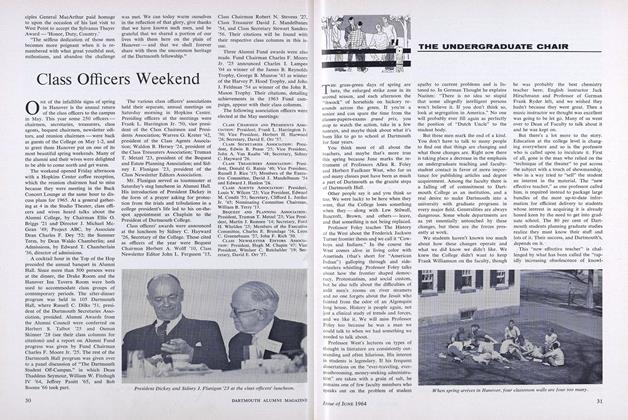

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

June 1964 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, JHON S. MAYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

June 1964 By WALLACE BLAKEY, ARTHUR M. BROWNING

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

JANUARY 1965 -

Books

BooksROBERT FROST: FARM-POULTRYMAN

FEBRUARY 1964 By C.E.W. -

Books

BooksTHE COMPLEAT BROWN TROUT.

June 1974 By DANA S. LAMB '21 -

Books

BooksLITTLE SAMMY CRICKET

February 1938 By E. P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksSCENERY FOR THE THEATRE

January 1939 By Henry B. Williams -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

May, 1922 By JOHN M. MECKLIN