By Franklin McDuffee '21, Commoner of Balliol College. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1924. The Newdigate prize for poetry, given annually for the best poem written on an assigned subject, is the highest reward for literary achievement that can be won by an undergraduate at Oxford University. Established more than a hundred years ago, it has been competed for by scores of men who in the later years of their lives have become noted in the field of English letters, its more celebrated winners including John Ruskin, Matthew Arnold, and Oscar Wilde. This year, for the first time in its history, the prize has been awarded to an American, Franklin McDuffee, who since his graduation from Dartmouth three years ago has been a student at Balliol College, preparing himself for his future profession of teaching-

McDuffee's winning poem now comes from the press in a small brochure of sixteen pages, and is of such unusual excellence that it merits a more extended review in the MAGAZINE than is ordinarily given to a work of this length. The subject assigned for this year's competition was "Michelangelo," but McDuffie has treated it in so spontaneous and original a manner that the uninformed reader would never suspect that the theme was other than the free choice of the poet. The poem is written in the traditional blank verse of the Newdigate poems, but here again McDuffee's originality obviates any possible monotony or1 stiffness, for he has introduced a short lyric into each of the five sections into which the poem is divided.

It has often been remarked that blank verse is the easiest of all English meters to write, but the hardest to write well. A single false note drops it at once into prose, and only poets with the genuine gift of song can keep it always at a high level. McDuffee proves his technical skill by the uniform beauty and smoothness of his lines. His accents are always sure ut never obtrusive, and his excellent variation of cesural pauses and of sentence lengths prevents any suggestion of that monotony which is the bane of less gifted writers. His vocabulary, too, is remarkably well-chosen for this meter, sonorous polysyllables alternating w.'th sturdy monosyllables to give that "organmusic" effect that is the glory of English blank verse at its best. .

But poetic technique alone never created a poem. It is McDuffee's beautifully imaginative handling of his subject that makes his work noteworthy. He has conceived of Michelangelo as a god among men, watched over throughout his life by the Spirit of Beauty and dedicated entirely to her service, and he has treated this theme in a manner that reminds us in some passages of a classic ode, in others of a modern threnody. In the introductory section of the poem, he compares, in a fine blank verse paragaph, his own wonder on first entering "the cities of the South," the land of Michelangelo's creation, with that of a lonely watcher of the crags and rocky passes of the moon, and adds a lyric on the mystery of the appearance in this dull world of such a genius as Michelangelo. The second section deals with the great artist's birth and his first inspiration by the Spirit of Beauty. Section three tells the story of his childhood, his first carving of a fawn's face, and Lorenzo de Medici's discovery and fostering of his genius. Then follows this singularly beautiful lyric: "This was the way of the golden time At Florence, in the south, When a Duke could bend to a noble rime As well as an upturned mouth. When the limbs that ripple in polished stone Laid siege to his gaze and heart With the warm-limbed maidens who throbbed and shone At Florence, the crown of art. A rose-fleshed woman? A flight to woo, Through flesh, to the heights above! A grinning faun's face? If art shines through As sure a claim to our love !

Thus it was in the golden days, But the gods no more endow, And down the world's trim garden ways No great Duke passes now."

The fourth section has to do with the days of Michelangelo's fame, and the loneliness of a god who must dwell in a world of men, while the subject of the last and in many ways the finest division of the poem is the sculptor's death and his translation into the eternal realms of Beauty. The concluding blank verse lines with their Shellevan suggestions and the final lyric stanzas that remind us strongly of the best of Arnold are so good that the reviewer is impelled to break the custom of the MAGAZINE and to quote them in full:

"Rome and her noises were no more to him; For with strong, steps and happiness unknown, And beauty leading, he had found his star. A twilight world it is ; and there the race Of noble forms his soul had brought to life, The Sons of Light that from the Sistine vault Assert God's grandeur, and. the eternal truth

Of beauty—these, and all the shining throng Of shapes tie made and dreamed of, dwell with him, Where moonlight is, and majesty, and peace; Deep peace, and majesty perpetual.

The twilight of the gods draws down apace. Grandeur is dead, and time is very old. Evening with swift foot and averted face Gofes: homeward, and the roads of life are cold. Come home, all wanderers : Make the doors fast. The long-enduring twilight shuts at last.

I do not know what sunsets may illume, As long night drops, the purple hills of home, Ere man, foiled lover, seeks the little room And everlasting coverlet of loam. Some final pageant yet may be unfurled Before time shuts the hinges of the world.

But, O, the morning and the morning star, The flush of dawn on uplands grey with dew, These come no more; and where the high gods are, Serene and pale, a darkness hovers too. Come home, all wanderers.; Make the doors fast. The darkness without stars has shut at last"

All Dartmouth men, I am sure, will rejoice not merely that one of their number has won a signal honor at. the great English Universitythough that in itself is a cause for congratulat'rdn—but much more that from their midst has arisen again, as in the days of Hovey, a poet with the true gifts of insight and of song.

'Michelangelo: the Newdigate Prize Poem,1924. By Franklin McDuffee '2l, Commoner of Balliol College. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1924.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe more one considers

August 1924 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMENCEMENT 1924

August 1924 -

Article

ArticleRECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES

August 1924 -

Article

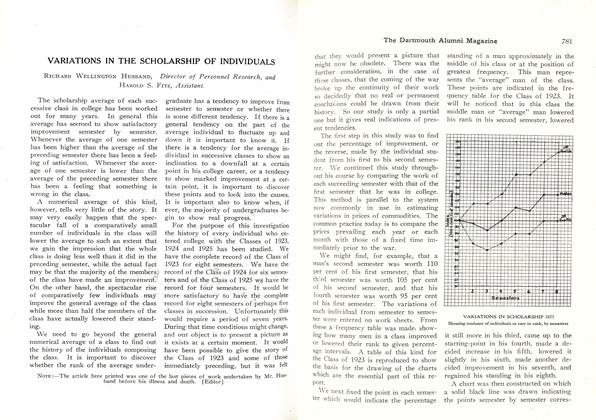

ArticleVARIATIONS IN THE SCHOLARSHIP OF INDIVIDUALS

August 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

August 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

August 1924 By Perley E. Whelden

F. L. Childs

Books

-

Books

BooksINSIDE TENNIS: TECHNIQUES OF WINNING.

OCTOBER 1969 By CARLTON PENNINGTON FROST '18 -

Books

BooksRAMON GUTHRIE KALEIDOSCOPE.

MARCH 1964 By DAVID SICES '54 -

Books

BooksTHE KID NEXT DOOR,

August 1944 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksDICTATORSHIP OF THE PROLETARIAT IN THE UNITED STATES,

November 1943 By Herman Feldman. -

Books

BooksThe Start of It All

September 1975 By J.H. -

Books

BooksRENAL FUNCTION: MECHANISMS PRESERVING FLUID AND SOLUTE BALANCE IN HEALTH.

December 1973 By ROY P. FORSTER