By James M. Cox. Princeton, N. J.:Princeton University Press, 1966. 321 pp.$7.50.

For most readers of Mark Twain this will be a very unsettling book because it makes reading him a difficult and, in some sense, a sad business. Difficult in that it shows as never before how alert, how wary one must be before every sentence of Mark Twain. Sad in that it reveals that the fate of Mark Twain's humor was to be self-destructive. Unsettling as it is, however, this is a good book and an important one, not to be missed by anyone seriously concerned with American literature.

Professor Cox leads his reader chronologically through Mark Twain's career, discussing all the major works and placing them in biographical context. Although he is primarily a critic rather than a biographer, he illuminates brilliantly the relationship between the life and the art of Samuel Clemens. In the Nevada territory Clemens went looking for silver and gold and instead found Mark Twain: "He had to fail as a prospector and later as a speculator so that he could succeed as a writer, for his very invention of himself as a writer is based not upon finding the proverbial pot of gold but upon discovering nothing - nothing but the resources of the comic imagination which can elaborate the futility of the territory into the material of humor." And once he had adopted his pseudonym (which Professor Cox nicely distinguishes in kind from other literary aliases), Clemens was committed to the "fate of the humorist." That fate, according to Professor Cox, was to be unable to be effectively serious on any subject. Thus, for example, the famous appreciation of the Sphinx in InnocentsAbroad, taken by many readers as high- minded reflection, on close examination threatens to "dissolve into burlesque."

Again and again Mark Twain confronts us with passages which seem to invite a conventional moral or aesthetic response, and Professor Cox shows that we accept the invitation at our peril. Mark Twain's failures, as in Personal Recollections of Joanof Arc, came when "he betrayed his genius by trying to be serious - which is to say that he put truth, virtue, and morality before pleasure." Conversely his greatest and, in the view of Professor Cox, his most daring success came in the denouement of Huckleberry Finn when Mark Twain shattered his reader's righteous moral expectation with a burlesque ending. "The more Huck berates himself for doing 'bad' things, the more the reader approves him for doing 'good' ones. Thus what for Huck is his worst action - refusing to turn Jim in to Miss Watson - is for the reader his best. When Huck says 'All right, then, I'll go to hell,' the reader is sure he is going to heaven." At this point, says Professor Cox, Huck is in great danger of surrendering his identity as a pleasure-loving boy and submitting to the tyranny of conscience. But while we remain stuck with the sentiment of moral approval, Huck fades into the irresponsibility of Tom Sawyer's escape game and finally runs off to the "territory."

This subversion of the moral sentiment, Professor Cox feels, marked the limit of Mark Twain's fatal humor and was a turning point in his career. From that time on Mark Twain tried to be serious. He became satiric rather than humorous, making his jokes out of moral indignation instead of irreverence. The end result was a series of failures (A Connecticut Yankee in KingArthur's Court, Pudd'nhead Wilson, TheMysterious Stranger) and a steadily deepening pessimism concerning man's capacity for rational behavior. So spare a summary can do no justice to Professor Cox's closely worked argument. The true value of his book proceeds from the constant operation of a sharp and subtle critical intelligence - which is happily equal to its subject - and that the reader is urged to experience for himself.

Fate, fatal, fatality, necessity, conscience - these words echo throughout Professor Cox's book. One is made to see that in some Calvinistic way Samuel Clemens was predestined to be Mark Twain, that Mark Twain's fate was humor, and that the fate of his humor was to devour its creator. Yet grim as this sounds, the effect of the book is not to inhibit our pleasure in reading Mark Twain but rather to make us read him with greater perception and hence with greater pleasure.

Chairman of the Department of English atDartmouth, Mr. Terrie teaches a majorseminar in Henry James.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

February 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

Feature

FeaturePlans Are Progressing for the Big Year

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureWhat It's All About

February 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

February 1968 -

Feature

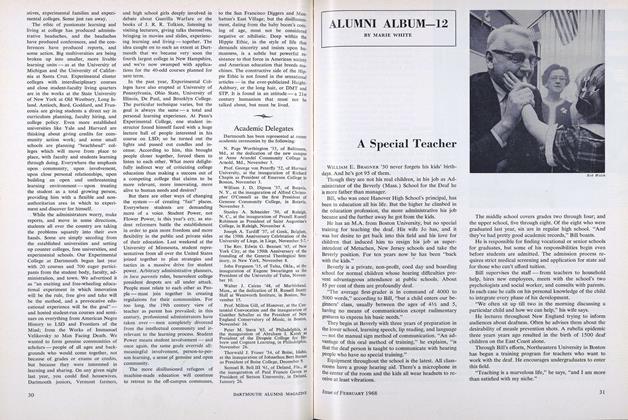

FeatureA Special Teacher

February 1968

HENRY L. TERRIE JR.

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JUNE 1969 -

Books

BooksTHE BEASTS & THE ELDERS.

January 1974 By ALEXANDER G. MEDLICOTT JR. '50 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN CUBA

February 1947 By C. F. Callahan '47 -

Books

BooksTHE CHRISTENING PARTY.

February 1961 By NOEL PERRIN -

Books

BooksCliff-Hanger

June 1980 By Peter D. Smith -

Books

BooksTHIS IVORY PALE.

NOVEMBER 1970 By WALTER W. WRIGHT