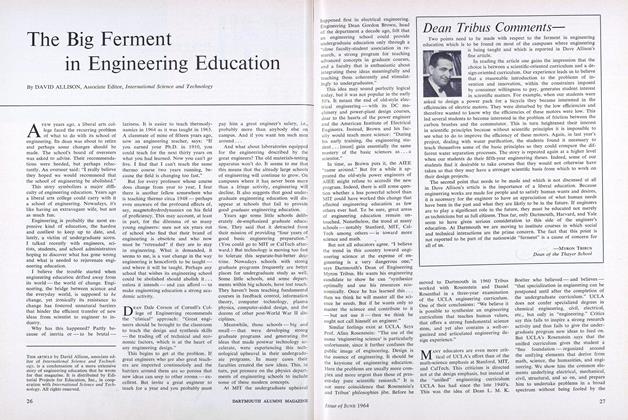

THE grass-green days of spring are here, the enlarged strike zone in its second season, and each afternoon the "thwock" of horsehide on hickory resounds across the green. If you're a senior and can spare the time from the classes-papers-exams grand prix, you stop to watch the action, take in a few sunrays, and maybe think about what it's been like to go to school at Dartmouth for four years.

You think most of all about the teachers, and maybe that's more true this spring because June marks the retirement of Professors Allen R. Foley and Herbert Faulkner West, who for us and many classes past have been as much a part of Dartmouth as the granite steps of Dartmouth Hall.

Other people say it and you think so too. We were lucky to be here when they were, that the College loses something when they - along with Lew Stilwell, Bancroft, Brown, and others - leave, and that something is not being replaced.

Professor Foley teaches The History of the West about the Frederick Jackson Turner frontier thesis and we call it "Cowboys and Indians." In the course the West comes alive in living color with Amerinds (that's short for "American Indian") galloping through and side-wheelers whistling. Professor Foley talks about how the frontier shaped democracy, Protestantism, and social custom, but he also tells about the difficulties of unlit men's rooms on river steamers and no one forgets about the Jesuit who fainted from the odor of an Algonquin long house. History is people again, not just a clinical study of trends and forces, and we like it. We will miss Professor Foley too because he was a man we could talk to when we had something we needed to talk about.

Professor West's lectures on types of thought in literature are consistently out-standing and often hilarious. His interest in students is legendary. If his frequent dissertations on the "ever-traveling, ever-mushrooming, money-seeking administration" are taken with a grain of salt, he remains one of few faculty members who speaks out on the problem of student apathy to current problems and is listened to. In German Thought he explains Nazism: "There is no idea so stupid that some allegedly intelligent persons won't believe it. If you don't think so, look at segregation in America." No one will probably ever fill again as perfectly the position of "Dutch Uncle" to the student body.

But these men mark the end of a kind. You don't have to talk to many people to find out that things are changing and what those changes are. Right now there is taking place a decrease in the emphasis on undergraduate teaching and faculty-student contact in favor of more importance for publishing articles and degree acquirement. Among the faculty there is a falling off of commitment to Dartmouth College as an institution, and a real desire to make Dartmouth into a university with graduate programs in every major field. Generalities are always dangerous. Some whole departments are as yet essentially untouched by these changes, but these are the forces presently at work.

We students haven't known too much about how these changes operate and what we did know we didn't like. We knew the College didn't want to keep Frank Williamson on the faculty, though he was probably the best chemistry teacher here; English instructor Jack Hirschmann and Professor of German Frank Ryder left, and we wished they hadn't because they were great. Then a music instructor we thought was excellent was going to be let go. Many of us went over to Dean of Faculty to talk about it and he was kept on.

But there's a lot more to the story. Education at the college level is changing everywhere and so is the professor who is called upon to inculcate it. First of all, gone is the man who relied on the "technique of the theater" to put across the subject with a touch of showmanship, who in a way tried to "sell" the student an interest in the material. The "new effective teacher," as one professor called him, is required instead to package large bundles of the most up-to-date information for efficient delivery to students whose interest in acquiring it is already honed keen by the need to get into graduate school. The 80 per cent of Dartmouth students planning graduate studies realize they must know their stuff and lots of it. Their success, and Dartmouth's, depends on it.

This "new effective teacher" is challenged by what has been called the "rapidly increasing obsolescence of knowledge," which demands that the professor stay atop the surging wave of new material flooding into all areas of study, particularly the sciences.

Education is no longer regarded as a "mysterious thing" which might come while staring out the Tower Room windows or skiing through a still pine forest. An unenchanted faculty member describes the process of higher learning today as being like "a Ford assembly line," with the college riveting onto the student new sections of knowledge at scheduled intervals.

Teaching may be of a less stimulating nature because it doesn't count so much anymore. In theory, teaching is of top importance, but a young instructor will tell you his teaching "is not regarded as a positive factor by the administration.' In fact, there would be no way of assessing it anyway, since his department, like most, has no system of checking classroom performance.

What does count for the faculty member are his publications - and his Ph.D. Many professors at Dartmouth and elsewhere, including some of the best, never got their Ph.D. Today a man can get a teaching position at Dartmouth without one, "but he must be in sight of it." A safe bet is that he will have it before being promoted.

"To stay here a man has to demonstrate his potential as a publishing scholar," frankly states a department chairman. When the Committee Advisory to the President has to pass- on a matter of promotion or tenure, publications are the "objective factor," says a member. This is not just because the publications are there in black and white, while the committee cannot visit the man's classroom. According to Provost John W. Masland, "We must be sure that a man is judged favorably as a scholar by his peers, not only at Dartmouth, but among men in his field elsewhere; also, any man we keep has got to have a potential for growth. His research and publications - and they must be good - are the best check we have on these factors."

As important, the "intellectual prestige" of widely known scholars on the faculty improves the College's position in the dogfight for teachers, foundation grants, and intellectually gifted students, as well as in the all-important estimation of the graduate schools. An English professor explains that if Dartmouth's faculty is known to the graduate school, this will add to the chances of Dartmouth students' being accepted there - and those acceptances are all-important today.

Officially, there are three criteria on which a faculty member will be judged by the administration - teaching, publications, and work in the business of the College. But of these teaching is the least tangible and publications the most easily weighed.

Publishing is not necessarily damaging to teaching. You go up to see a man who regards himself as research-oriented and find yourself cooling your heels for half an hour while he finishes with students fired-up enough about his course to stay and ask questions for an additional class period. Then he sits down at his desk and rattles off the names of the men in your major department who are most interested in research, and you have to admit these are among - though not all - the better teachers in the department. If you start to agree that the man who is deeply involved in his subject is also one who will want to get his students interested in it, and concede that someone totally uninterested in teaching wouldn't be at Dartmouth, then your case against "publish or perish" doesn't look so good.

But publication as a success indicator has its drawbacks. Professors will pass on in confidence stories of "non-publishers" who were let go only to publish and give credit to another school for ideas that were in gestation here. And the need to publish and the emphasis on research slice into the time a faculty member might spend on his students. If there is a rapport between students and teacher on the basis of the subject matter, this is where the relationship now ends. For. the teacher there is not the time, and frequently not the inclination, to extend it. The idea that the professor can give his students something more than what's in the syllabus, something moral or profound about life, is not current among the newer members of the faculty. One of them puts it that the "Mr. Chips" style of professor is "on the way out."

The allegiance of this "new faculty" belongs not so much to Dartmouth College as to the academic profession, particularly to the group of scholars across the country and now even throughout the world who are at work in the professor's particular area of study. Instead of "loyalty" a chairman uses the word "morale" in discussing his department, and that morale, he says, is high. An instructor says he finds the College a pleasant and satisfying place to teach, and a young associate professor reports the feeling that Dartmouth is already "quite good and getting better" and that he feels a personal stake in "continuing that improvement."

It is in part to help Dartmouth keep its best men that increased graduate programs are recommended. Professor John G. Kemeny, chairman of the Mathematics Department, explains, "It is very hard to ask a man to come here for the rest of his career if he knows that he will never have an opportunity to teach a course in his specialty on an advanced graduate level."

Graduate studies have been introduced in mathematics, engineering, and in other more limited programs. In mathematics the pitfalls seem to have been avoided and the program appears a spanking success. With computerized exactitude they announce that the percentage of department load consumed by the graduate work barely, if at all, exceeds the programmed 20 percent. The size of staff and facilities were expanded to compensate for this increment so the effort on the undergraduate level remains precisely the same.

Homework grading and problem sessions are conducted by graduate students, but these sessions are optional, extrahour classes. Four times a week students in even the introductory courses are lectured to by the top members of the department.

On the positive side, the opportunity to do teaching on both? the graduate and undergraduate levels has enabled Dartmouth to gain two nationally known mathematicians against the toughest possible competition.

The large lecture methods used in mathematics are not, perhaps, as applicable to - the introductory courses in English or the languages, and the problems of introducing graduate programs are compounded in other ways for the social sciences and humanities in general. But the same advantages remain and serve to lure the College in the direction of becoming a university.

Maybe this is nothing new. President Dickey is reported to have said that Dartmouth has been a "university" since the medical school was founded in 1790. However, in 1887, Samuel Colcord Bartlett, then president, said, "We do not aspire to a university, fashionable though it is . . . our higher aim is to do such work, whether it be for few or many, so that the same high character that has marked the graduates of Dartmouth College as a class for the last 100 years shall continue for the next 100 years to come." This set the tone for Dartmouth's policy almost to the present. There is probably no doubt that the present course of Dartmouth is not exactly the one charted by her earlier leaders. But then, the College hasn't educated many Indians lately, either.

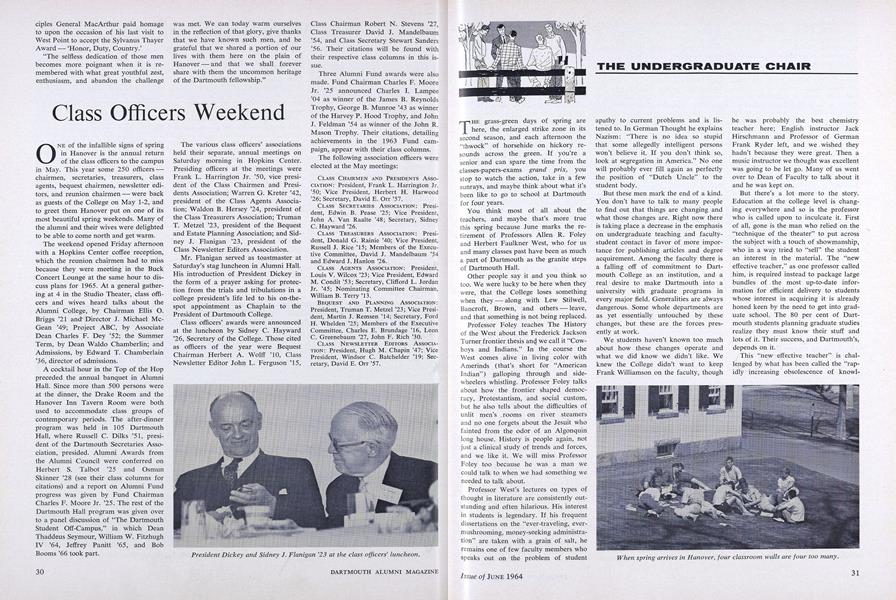

When spring arrives in Hanover, four classroom walls are four too many.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Big Ferment in Engineering Education

June 1964 By DAVID ALLISON, -

Feature

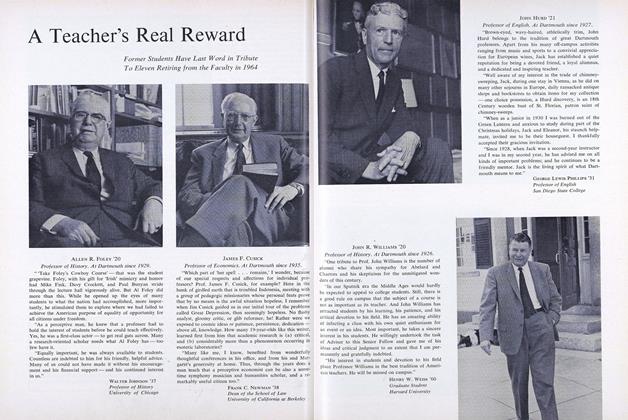

FeatureA Teacher's Real Reward

June 1964 -

Feature

FeatureSports for the Multitude

June 1964 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

June 1964 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, JHON S. MAYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

June 1964 By WALLACE BLAKEY, ARTHUR M. BROWNING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1946

June 1964 By ROBERT Y. KIMBALL, FRANCIS T. ADAMS UR.

DAVE BOLDT '63

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleDanube Adventure

FEBRUARY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63