The text of President Dickey'sCommencement Address, June 7,at Bucknell University where hereceived the honorary Doctor ofCivil Law degree.

THIS occasion has for me the happiness of coming home. It brings me back not merely to the central Pennsylvania of my boyhood, of my family, and of my friends but also to the university where I first began higher education. I attended Bucknell in the summer of 1925 on my way to Dartmouth from Lock Haven High School. I lived in West College on the hill, I dined in Women's College, I was awed by the lords of the fraternities (being displaced from their castles they were especially lordly in the summer, I guess), and most importantly, I was well introduced to college work by Miss Clark, later Dean Clark, who then taught French, and by "Docy" White who - dare I say it - started me at that tender age of seventeen down the primrose path of public speaking.

So, if like most college seniors, you are still a little ambivalent about your college, and are looking for a last opportunity to be critical before taking it as your alma mater to cherish till death do you part, I suppose you might fairly regard having to listen to me as just one more unnecessary hardship for which Bucknell has no one to blame but itself. If I do serve as a lightning rod for the discharge of any last negative feelings, I shall not count this day lost because it will bring you a little closer to the day when in mature appreciation, like most American college graduates, you will realize that in a very personal and profound sense you and your college are truly and wonderfully one. Every worthwhile relationship needs the stimulus of a little animus - ask any happily married couple. (There is no need to ask the others!)

My animus for the day is to be found in my unwillingness to follow the tradition of the commencement speakers who on behalf of their generation, year after year, plead guilty before the bar of our graduating classes to having made a mess of things which, as they say, "you will have to clean up," not only in Washington but everywhere on earth, and now presumably even on the moon.

I have no doubt about the fact that you are not about to be the first generation to enjoy an inheritance of heaven on earth. I do suggest that you inherit a world which could easily have been much worse. If when it comes your turn to make commencement speeches you can say that your generation kept the pace, as well as the peace, it would be my guess that the twentieth century will long be known as the period of mankind's coming of age. I need hardly remind this graduating class that any "coming of age" is not a period of innocence without danger.

We might usefully recall a few of the things my generation of commencement soothsayers has been through, shall we say, during our forty years of wandering - and wondering - in the wilderness. We began, as usual, by shocking our elders. We were the flaming youth of the twenties. We professed to burn the candle at both ends but without, I fear, any noticeable increase in light. We did raise the level of noise and got our particularly brassy immaturity dubbed "The Jazz Age." We tried national prohibition and after fifteen years repealed it. Both actions were, in my opinion, a credit to our society: the first to its idealism, the second to its realism. And paradoxical as this chronology may sound, we then sobered up in a depression that for the better part of the thirties taught my generation that life is real and life is earnest and determined men can do something about it.

Determined men do not always do the right things. That, as I hope you suspect, is where you and your education will be put to the test. If all goes well I shall stand between you and that testing for another ten minutes or so and this will permit me to try to make the point that you are going to have to work rather harder than your predecessors did in deciding what are the "right" things to do.

For better or for worse, and I think for the better, my generation has largely deprived your generation of the possibility that doing nothing is usually the best public policy. It would be gross over-simplification to suggest that anything as fundamental as an activist public philosophy came to America in any particular period. It has come to us from our entire history and, let it quickly be said, it came from both sides of the political fence. We might even say that it came from one Roosevelt as well as from the other. How is that for bipartisan purity? Parenthetically, it reminds me of one of the better political stories I heard on a visit to Poland several years ago. A non-party professor inquired whether I knew the difference between Soviet socialism and German national socialism. In response to my negative head shake he said with unprofessional glee: "It's very simple, national socialism is the exploitation of man by man and socialism is just vice versa."

A commencement speaker must be non-partisan — all else is either forgiven or forgotten. I can only hope that it will not sound in the slightest degree partisan if I reiterate that my generation has left you little alternative in any area of public policy except positively both to seek and to create better answers. Make no mistake about it, any such seeking and creating means playing with matches. It also just might mean lighting the way a little further into the darkness, and how wonderful that would be. If perchance there are a few unplanned fires along the way, you can take a little comfort in Francis Bacon's counsel that "ashes are more generative than dust."

Out of the ashes of World War I and our rejection of membership in the League of Nations we learned some hard lessons. We learned that the destructive expenditures of war which we then knew as the War Debts could not be collected from our allies like the loan you will probably be using to buy your first washing machine. There wasn't any washing machine to be reclaimed, and even if they made one, our tariff policy frowned on any such trade shenanigans as a way of getting our money back.

Yes, we went through the essentially negative, isolationist aftermath of World War I; we tried getting along with a monumental fool and a monstrous knave, Messrs. Mussolini and Hitler; we were of two minds about international communism, and we negotiated with the facade of a civil government in Japan until Pearl Harbor. However, when World War II broke on us we fought it on issues that united the nation and with our allies we won it on a basis that - the machinations of international communism aside - has produced the most creative and positive postwar period the world has ever known.

I, of course, realize the cold war and its hot counterparts, the Korean and Vietnam wars, cannot be put aside for one moment. The point I would leave with you is not that these troubles are unimportant. My point is that the world before you is far greater and much better than its troubles and that in no small part this is so because your country, the most powerful nation on earth, has learned - and I emphasize learned - to behave with a maturity that for all our shortcomings does the democratic process proud.

WE might begin with the way World War II ended. Some feel that requiring the unconditional surrender of the Axis powers was an idealistic mistake. I understand the argument and there might have been a better way, I just am not sure. I am very sure, however, that there were many worse possibilities than unconditional surrender. As I look back on the difficulties of handling any other course with our allies and our own publics, let alone those particular enemies, I doubt that that war could have been brought to a better end.

In any event let us remember that even before the fighting had stopped in Europe and five months before the Japanese surrender, the victorious nations with American leadership were at work in the spring of 1945 at San Francisco establishing the United Nations organization. It is so easy today to see nothing but the troubles that becloud the UN and to forget the alternative we might have with us - a world without any experience in creating a true international community because the most powerful nation, the U.S., was unwilling to participate. The changing of a great nation's mind on anything so fundamental within one generation is something worth your understanding and your remembering.

May I also urge that you find time in between the imperfect joy of raising your family and the precarious task of raising your salary to remember that you and the family you're raising are the stuff of a nation that had the maturity and the vision to put its wartime enemies back on their feet with two of the most enlightened enemy occupations ever recorded in the affairs of nations. Beyond this wisdom and this magnanimity toward vanquished foes, your country has been generous to a fault toward its friends. I shall not here attempt to say how much "fault" since there is always a long line waiting to offer such testimony. I will offer the judgment that few foreign policies have done as much to keep the future open for your generation as the Marshall Plan.

I am also confident that the judgment of history will say that fighting the Korean War under the aegis of the United Nations gave your generation its chance at keeping the peace in the name of the international community. We could, of course, have gone it alone; we could have dropped "the" bomb in our own name, and we might have "won" that particular war rather than having merely arrested aggression. No one can be sure about such "might-have-beens." If you are ever tempted, however, to believe that going it alone might be easier, and that there's no point to having "the" bomb if you don't drop it, I urge that you also reckon with the even more likely contingency, namely, that we would soon find going it alone more lonesome than anyone, including the most embittered UN critics, ever bargained for. It may just be that all the nations are as yet too immature to do anything but "go it alone" - while pretending otherwise. If unhappily that should be proven so, let us at least not now make the fatuous mistake of imagining that we are going to like that kind of destruction more than we do today's danger.

During the past fifteen years national independence has come to fifty or so new nations. The liquidation of colonialism means a tremendous alteration of the structure and functioning of the international community. Many doubted that it could ever come without plunging the world into unlimited violence. It has not come about without a measure of violence. It is still in process of being accomplished, but by and large the big decisions have been taken and they have involved less trouble than many men feared and most communists wanted.

I am sure that few of you in this graduating class can have even the remotest idea of the difference to your generation of having the idea of colonialism behind you. Hard problems have been created by this development, but in the main they are the right problems rather than the wrong ones. Your energies, your earnings, and perchance your lives can be spent on problems that face forward from colonialism rather than backward into the jungle of exploitation and imposed inequality.

That last thought brings us back from foreign affairs to your inheritance here at home. Is there one among us who, regardless of how he or she feels about specific situations in America's civil rights crisis, does not know deep down inside, where everything finally counts, that for the first time in a hundred years Americans are facing the right problems in our racial relations rather than evading them? You will not readily or easily bless my generation for bringing you uncomfortably face to face with the issue of human equality. I do suggest that you may see the matter differently after you have had enough experience with this crisis to compare the outlook for your children with that of the white children yet to be born to your generation in South Africa.

I HAVE not pulled these plums from the pie of our time with any thought of playing little Jack Horner for my generation. And I certainly do not presume to instruct you in history. I do admit to a mild hope that you will be a little fortified against feeling sorry for either your generation or mine. I might even hope that you will conclude that anything we can do, you can do better. However, before you do that, I want to leave with you the transcending hope this record of national behavior offers all of us. It is that our democratic process has now reached the point where it is capable of functioning as the great teacher of our society.

Have you as yet ever thought about democracy as a teacher? I know that in my own case it was a long time after college before I did. We are mostly brought up to think of our democracy within the Republic as the constitutional process whereby laws are made, rights are fixed, the majority has its way, the minority its say, and all of us are governed more or less with our consent. It is, of course, all of these things and I shall not presume to say that any aspect of the democratic ideal is more important than another.

On this occasion of your going forth from college to buckle on the sword of full-fledged citizenship I do, however, want to urge on you the less obvious truth that whatever else democracy has in common with other systems, at its best it is uniquely the great teacher of the community. I hope you are already ahead of my saying it in knowing from your own experience here at Bucknell that the only great teachers are those who in one way or another induce you to learn something on your own. So far as I can see, democracy is the only form of human discourse and decision that can conceivably give a community the experience of learning its own way into the paths of fairness, wisdom, and fulfillment.

Even Americans are not born fair, wise, and fulfilled. Individuals and nations alike must learn and work their way to these human harvests. There is no other way.

It takes no great knowledge of history to know that our nation and all nations have had a great need to learn from experience. It should not surprise us that in every time individuals have far outdistanced society in self-education. I hope and assume it will always be so, but let us not blind ourselves to the truth that societies as well as individuals can and do learn. I truly believe that American society is at a point today where your generation has the possibility, but not the certainty, of using the democratic process to educate itself and thereby fulfill itself as no society in its entirety has ever previously come close to doing.

I have mentioned only a few selected examples from the public record of my time that give me confidence in the capacity of our democracy both to teach and to learn. Others might cite the wondrous advances of science and industry, the conquests of illness, the exploration of outer space, the growing rationality toward the world's population and the use of its resources, a revitalized ecumenical movement, the spreading enjoyment of the arts, the Peace Corps, the host of private humanitarian causes, and perhaps above all the demand for and support of first-rate education in our schools and colleges. All these and much more are a part of your inheritance. In my view these good things far outweigh the taxes and the troubles that go with the inheritance of any great estate. And now, whether you agree with my appraisal of your inheritance or not, it is yours for the managing.

Please permit me just one word of exhortation: Never, never forget that you enter upon your lifetime learning of citizenship with the handicap of being the "rich kids" of the world. If "rich-kid" America is to learn its way into a worthy future, it will be because you have it deep down inside you to keep our democratic process as the great teacher to your generation it has been to mine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Heritage and An Obligation

July 1964 By SIGURD S. LARMON '14 -

Feature

FeatureQuebec in the Modern World

July 1964 By THE HON. JEAN LESAGE, LL.D. -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1964 -

Feature

FeatureLandauer Heads Alumni Council

July 1964 -

Feature

FeatureA Look Backward and A Look Ahead

July 1964 By MICHAEL JAY LANDAY '64 -

Feature

FeatureAnother Record for Reunions

July 1964

Article

-

Article

ArticleCONNECTION FOUND BETWEEN COLLEGE AND PRESIDENTELECT HARDING

January 1921 -

Article

ArticleDEAN BILL SPEAKS AT PREPARATORY SCHOOLS

MARCH, 1927 -

Article

ArticleMr. Tuck Recovers

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Article

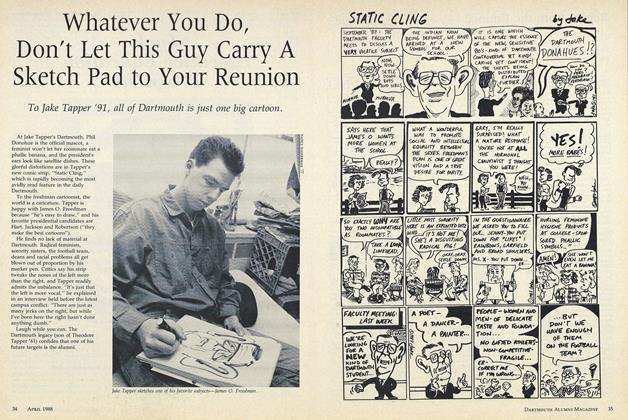

ArticleWhatever You Do, Don't Let This Guy Carry A Sketch Pad to Your Reunion

APRIL 1988 -

Article

ArticleIn Brief

June 1989 -

Article

ArticleELECTIONS

OCTOBER 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32