A report on motivation and ideology of students as civil rights workers, mainly with COFO, based on Prof. Segal's research this spring in Mississippi.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY

1. Moderation ...

A Mississippi moderate, a man of great personal integrity who has probably done more than any white person in his town to ease racial tensions there, recently made this comment to me in a personal conversation. "You want to try to understand why people in Mississippi reacted the way they did. Try thinking how you'd feel if you kept getting told that a couple of thousand outsiders were coming into where you lived, into New Hampshire, saying they were going to change things all around. People don't like to be told that everything about them is wrong. Of course we have a hooligan element, too, but we aren't proud of it. Most people here disapprove of violence, and they don't like extremism on either side."

Asking for a period of calm, he would like time - time for men of good will of both races to be able to come together to arrive at amicable agreements. Others like him, generally somewhat sympathetic toward the Negroes' drive for civil rights, also would like to be left alone for a while, "to have a little rest, a little breathing space." These are apparently reasonable requests from reasonable men who accept the inevitability of change in Deep Southern patterns of race relations. At the same time, they are the requests of men whose social positions, as well as their training and temperaments, incline them to hope change will occur slowly enough to be neat and orderly. Implicitly, such men tend to define situations in their own terms. They forget, for example, that in Mississippi, but not in New Hampshire, a large proportion of the population (mostly Negroes) eagerly awaited change and looked forward to the outside support which could help to accomplish it. They also forget that in recent years the significant changes which have occurred in Mississippi's race relations have had to be imposed on the state by the Federal government to be effective.

It is true that the moderate position does shine brightly in comparison with the vulgarity and brutality that occur among the advocates of total resistance to desegregation. It is also true that moderates in Mississippi have reason to fear violence, as well as social and economic reprisals, if they state their case too forthrightly. Although it is far more comfortable and much less threatening to be a white moderate than to be a Negro in Mississippi, it is not easy.

Nevertheless, and despite the courage displayed by a number of outspoken white newspaper publishers, for example, the Mississippi moderate's plea is essentially for stability rather than justice. Moderates do try to accommodate themselves calmly to whatever changes are imposed. On the other hand, they do not take the initiative in suggesting specific areas where racial changes could be implemented, and they are unwilling to grant that it is legitimate for Negroes to continue using those techniques of demonstration and protest which can win enough outside sympathy to guarantee change and can shape enough solidarity in Negro communities to begin to secure it. A southern historian, Ernest Lander, might have been addressing himself to these reasonable and moderate Deep Southern business and professional men as much as to his scholarly colleagues when he pointed out that

"... when forced to it, most southern whites have accepted these changes in fairly good grace, in South Carolina and Georgia perhaps more so than in Mississippi and Alabama. But, if there is a white person in the Deep South who believes the articulate and educated Negro is satisfied with segregation or even token integration, I can only suggest that he attend an inter-racial meeting of a council on human relations in a southern state. He will quickly be disabused of such a notion."*

2. ... and Impatience

The most active participants in the civil rights struggle in Mississippi, SNCC and CORE workers and their cohorts at COFO offices around the state, are articulate and generally well educated. Their suggestions go a good deal further than Lander's. In fact, on encountering a statement like his, they would almost certainly suggest that the person who made it find some way to leave the southern white world long enough to be able to talk openly with the great numbers of less polished Negroes who have grievances and aspirations of their own, but never get the chance to attend inter-racial meetings where white men shake black hands.

COFO workers identify themselves with the poorly educated, less articulate, and most populous working- and lower-class segments of Mississippi's Negro population. They are impatient with counsel of the kind that stops after urging white men to be tolerant of Negroes' attempts at self-improvement. They argue that collective exertions by Negroes against a repressive social structure are also called for. Otherwise, they think, it will take too long before an appreciable number of people from so large and so deprived a group as Mississippi Negroes will be able to upgrade themselves. No genuine individual success without collective success, COFO workers seem to be saying; no one can really rise to the top when most of the group from which he comes is still held back, unable to compete on an equal footing with members of the dominant white sectors of the society. In the COFO view, individualistic techniques of self-improvement that are favored by both Negro and white middle classes may apply in the future, but not in the present situation. Therefore, calling attention to a thin trickle of upward mobility among individual Negroes is illusory because it notes the progress of the few but neglects the obstacles which block the many. It is self defeating, too, because upward mobility draws away prospective leaders of the lower-status mass and encourages others to focus on their own goals rather than contribute to a collective effort to open the opportunity system to everyone.

COFO staff members also look beyond that portion of equality that can be won and secured by law, insisting that full equality depends upon the recognition of the essential human dignity of all men of whatever status. They call for a different way of judging and evaluating men, in place of conventional standards of propriety and respectability and the material symbolization of success. It is as if they were saying that conventionality and the props and costumes of middle-class life are mere superficialities. Yet they have been important, for those who have possessed them have taken pride from them, and have assumed, with or without malice, that the lower-class Negro who did not possess them could not have as much claim to humanity as the middle-class white who did.

Despite their readiness to question norms and standards which most people take for granted, COFO workers know that they cannot realistically expect freedom now. This does not keep them from looking forward to it in tomorrow's now, or from working hard to get it. In town after town, through personal example and formal teaching, their major activity consists of urging and helping to prepare Negro communities to seek freedom on their own behalf. When demonstrations, protest marches, and boycotts seem to be possible and effective tactics in this effort, COFO workers will not hesitate to employ them. Furthermore, demonstrating has become part of a larger effort that is increasingly politically-oriented. The purpose of demonstrations is no longer merely to desegregate lunch counters or to force negotiations with employers. Demonstrations are now being considered significant in that they provide a focus for the attention of Negro communities and can supply community members with a means whereby they become accustomed to collective participation in the pursuit of common goals. This practice in working together to accomplish an immediate local aim is training for later political participation, and particularly for learning that political solidarity can be employed for achieving changes that appear more distant but are wider in scope.

COFO is aware that its encouragement of demonstration and active participation may stimulate forceful and violent reactions from some sectors of white communities. Because COFO workers accept this possibility as a responsibility, they feel obligated to justify their own roles to the extent that their activities endanger others. One way they try to do so is by insisting that no single individual is indispensable to the Movement as a whole; most emphatically they include themselves in this judgment. More concretely, and partly because they recognize the particular part they play in calling forth white men's wrath and indignation, they assign the most dangerous tasks to themselves, and are always ready to be in the front of the line.

Perhaps it takes a clinician to judge fairly where valor or nobility ends and recklessness or masochism begins. My own impression is that most COFO workers do not so much court danger as accept it. They are not fearless. Somehow, though, they manage to overcome their fear by relying on gallows humor and the solidarity of comrades, and - most importantly — by immersing themselves in a cause they sincerely believe is much greater than themselves.

Older heads might suggest the strategic wisdom of a different approach, perhaps one which favored negotiation over demonstration. To this COFO workers would respond that they are quite prepared to negotiate, but that it is often necessary to demonstrate first, in order to create situations in which they can negotiate as equals. They reason that the white community must see that its own interests are at stake before it will be prepared to deliberate over issues which are relevant the concerns of the Negro community.

Other observers might point out that COFO ought to try to work more closely with white moderates. This policy might give the more mature and more sophisticated elements of white communities an opportunity to bring their influence to bear. To this COFO workers would reply that the more moderate whites are not in control in most areas of Mississippi, and that when moderates do speak up, they offer little but tokenism and gradualism. Tired of these, the civil rights workers point out that they are working for changes greater than the ones most whites are readily willing to grant.

3. "Maybe if they wentaway ..."

In the long run, as Mississippi continues to change from a near-feudal society based on a predominantly agricultural system to one based on a more modern, more industrialized economy, its patterns of race relations will also change. But broad-scale economic transformations of this kind, taken by themselves, should by no means be regarded as offering the solution to problems of racial inequality. Obviously, the long run may be long indeed, while Negro communities daily become more restive and more skilled in taking the initiative to accomplish change on their own account.

Consider Birmingham, Alabama. It is bigger and a good deal more "modern" than any city in Mississippi. Highly industrialized, it has a complex division of labor based on technical criteria, along with a characteristically urban crispness and impersonality. But who would claim that racial distinctions are not still enormously significant there? Who would be prepared to argue that the changes which have occurred in Birmingham's racial patterns would have happened if the Negro community had not organized itself to show the rest of the country how dramatic were its grievances? Industrialization may well provide the groundwork for new forms of community organization and for new ways of demonstrating complaints, but clearly it cannot be taken as a sole and sufficient cause for broad changes in traditional patterns of social organization based on racial distinctions.

The last point is relevant to this discussion in still another way. Observers of areas eager to undergo rapid economic and social development - as Mississippi is - frequently point out that modern technology and plant organization call for a free and mobile, technically competent labor force. The generalization should not be applied too facilely to race relations in Mississippi and other Deep South areas, for there the question involves national rather than regional occupational patterns. New labor and staff come in, but they are white. The lessskilled Negro laboring classes, left to their own devices and with no provision made for them, have in the past had little choice but to get out, even in places where the Old South was in the process of becoming the New South. If this population exchange were to continue in Mississippi, it could well help to ease that state's racial tensions. It would do little, however, for many of those who chose to migrate only to encounter even more rapid automation and de facto segregation.

COFO workers, who would like to make the "solution" by migration nothing more than an idle dream entertained by members of White Citizens' Councils, emphasize the last point rather strongly. They insist that the North is no paradise, and they urge members of Negro communities to stake their claim to Mississippi as home. Mississippi Negroes, they say, have as much claim to the state as white men; the plantations, the towns, and now the factories have been and are being "built on black backs." Moreover, changes in the direction of freedom and equality are already occurring. As COFO workers see it, and as they try to persuade others, an individual's part in contributing to these accomplishments is an important basis for self-respect and for claiming dignity through achievement. As for the terror and the violence, these are an old part of Mississippi history, and a people that has been able to survive them for generations now has before it, for the first time, the possibility of outliving them.

Every COFO office has in it at least one Negro native of Mississippi. Some are college graduates; others have not finished high school. All of those with whom I talked felt strongly obligated to work with other Negroes who either chose not to leave the state or did not know how to go about leaving. Recently a program has been launched to recruit and train more Mississippi youngsters, mostly of high-school age, for work in the Movement. At this time it is difficult to tell how successful the program will be, although it is worth recalling that SNCC itself was in large measure formed in similar fashion. In any case, the program's aims are clear. One is to develop a larger core of active, indigenous Mississippi leadership drawn in particular from the more deprived groups who constitute the bulk of Mississippi's Negro population. Another less obvious aim is to give a number of young people in the state a good reason for staying in it by contributing to the political and social development of its Negro communities.

Native Mississippians and out-of-state staff and volunteers at COFO are in strong agreement on a number of points. Now is the time when, as bad as Mississippi is, there is no place else for a Mississippi Negro to go. Places like McComb and Vicksburg must be reshaped because places like Harlem are also nearly intolerable, particularly for recent migrants. Now is the time when Negro communities must learn to use all the political force at their disposal to insist on better schools, in order that their children have the chance to acquire the training that will be necessary for new jobs that will be available. Now is the time, as industry is moving in and new employment patterns are not yet fully established, for Negroes to insist on equal employment and on equal participation in industry-sponsored training programs and job promotion plans. Now is the time when the cry for freedom should mean asking for more than the kinds of encapsulation and envelopment that hamstring racial ghettoes in the urban North.

Most COFO people think that the most effective way to reach these goals is to change the character of state and local political structures and representation. COFO's support of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party rests on the belief that Mississippi Negroes must establish an independent and genuinely democratic political base, not to supplement but to replace the regular Democrats. COFO also insists that Negroes must be prepared to demand a genuine and not a token voice in Mississippi politics. This does not preclude - although it is obviously likely to discourage - white participation in the FDP. Even if the new voting rights bill is adequately enforced, COFO sees little prospect of Negroes being able to bore from within the regular Democratic Party where white professionals will probably still control the party apparatus. In theory, the assumption is that responsible, non-racist government will emerge more swiftly if Negroes can elect some candidates of their own, thereby demonstrating that white office-holders also have good reason to be concerned about "the Negro vote." In fact, the FDP may be more important as a symbol and as an organization for developing potential political leaders.

4. "Three dollars a day ...must go!" - a picket linechorus

A glimpse into what COFO workers mean when they speak of "changing the structure" is that they hold out the prospect for Negroes in towns like Greenville and Meridian (and ultimately even in the rural areas, like Amite and Sunflower counties) to be better able than those in cities like Chicago to exercise genuine determinations of political, economic, educational, and even residential choice. Small wonder that so large a part of white Mississippi sees COFO as an organization devoted to agitation. Visionary thinking of the COFO kind is almost as disturbing to the more moderate middle class as the upsetting of restrictive traditional racial patterns is to more rabid segregationists.

It is not difficult to understand why this should be so, considering some of the basic ideological premises underlying the COFO perspective. Two central themes of what might be called the COFO creed are, first, that much of the present advantage of relatively high status in a Mississippi white community, including comfort and unearned prestige, depends upon the exploitation of a fairly sizable group of underpaid and politically powerless Negroes; second, that there must be an end to the nearly automatic perpetuation of these racial status advantages across generations.

This second point warrants being spelled out a bit further. As COFO people see it, Mississippi Negroes have labored under oppression for scores of years. For that reason in particular the children of the present generation of adult Negroes should come to realize that they have as much right as the children of white people to comfortable adult positions. Now no one at COFO thinks for a moment that status equalization can take place overnight. Far less does anyone claim that Negroes ought immediately to replace whites at all the command posts of the state and its communities. What COFO workers do believe is that it is crucial for more money to be spent on de facto Negro schools than on white ones until the two are equally good; for private industry to do more than its conventional share by hiring Negroes for jobs for which they might still need on-the-job training, rather than taking on only those who already have the requisite skills; for municipalities to pave and light streets in Negro areas for the first time in addition to repairing the pavement and lighting that already exist in white areas.

To press these points is to ask that available financial resources, public and private, be applied and distributed in new ways. Requests like these would be disturbing to many white people in the North, let alone in Mississippi. Picture the response of a typical resident of an upper-middle-class suburb to the suggestion that he pay higher taxes for the purpose of bettering slum schools in the neighboring central city. It is hardly news to point out that in Mississippi there is an even larger gap in the economic and financial resources available to white and to Negro communities. An individual who told white Mississippians that there was therefore an even greater need to distribute these resources in a way that would narrow that gap would be considered a trouble-maker. If in addition he were found attempting to explain the same proposition to members of a Negro community, he would be branded a revolutionary as well. In terms of Mississippi's present social structure and climate of opinion, the judgment would not be far from wrong.

5. "Sometimes you just gottaget away"

In the national as well as the Southern press, SNCC in particular has been characterized by a number of terms with sinister overtones: extremist, militant, radical, way out. In fact, SNCC workers have occasionally been involved in episodes of reckless bravado and in quests for critical confrontations which sometimes appear to be of questionable significance to the over-all strategy of the civil rights movement. In my opinion, such an event occurred in Montgomery on March 16. Just then, Dr. Martin Luther King was preparing the march from Selma to Montgomery, and events in Selma and Marion had already stimulated about as much Northern sympathy and federal support as could have been generated for the Alabama movement at that time. But in Montgomery, SNCC staff members took part in a street demonstration to which the police responded with great vigor, injuring several of the demonstrators. In terms of a perspective taking in all that was then happening in Alabama, one may for the moment put aside such otherwise worthwhile questions as whether or not the demonstration was constitutionally legitimate, and whether or not the police response was brutal. With the advantage of hindsight, it now seems worth while to ask a different question, namely, whether or not the demonstrators risked their own safety and provoked white opposition without adequate consideration of such other goals as increasing community solidarity, or winning more national support for a strong voting rights bill.

Nevertheless, it is important to try to understand events like these. Though well publicized, they are in fact relatively rare, and they are not typical of SNCC or COFO organizational techniques or of the character of most of their staff members. Most of the time, these people are perfectly well aware that it is foolhardy to demonstrate for its own sake, or merely to prove courage. Thus I think that these less well considered episodes are better regarded as impatient and impetuous expressions of great tensions which the workers ordinarily need to keep under wraps almost constantly. For example, non-violence is tactically sound, and it does provide a sense of strength and dignity to those who act as well as espouse it. But it can also be frustrating, especially to young people who do not believe in it as a central point of a broader theologically grounded doctrine, and who have been taught to think that a man who doesn't fight back when he's attacked is a coward.

To keep these matters in proper perspective, it is necessary to record some more prosaic observations about COFO's efforts. Its workers' pleas and encouragement frequently fall on deaf ears, and often the number of people COFO can rally to its causes seems pitifully small in relation to the enormity of the tasks it has set for itself. Both of these points apply with particular force to the rural areas of Mississippi, where three interrelated conditions combine to make civil rights work extraordinarily difficult. First, as compared with the Negro populations in the good-sized towns, those in the rural areas are far less enlightened and considerably more afraid. Next, the population is dispersed and, in the plantation country, it is nearly completely dependent on white property owners. This not only means that there are few bases for establishing sentiments of community solidarity, but also that COFO workers must travel considerable distances in relatively isolated country alone or in pairs. Such travel is no small feat, in view of the final point, which is that the rural areas are under a type of tight conservative control which appears to have remarkably few recriminations about tolerating, if not actually employing, physical terror as a means of keeping a tight grasp on power.

There is terror in some of the towns, too, although much less marked in some of them than in others. Even so, COFO workers need great patience and self-control in order to withstand anxiety provoked by physical danger on the one hand and by ennui on the other, as they work and wait for issues to arise which can crystallize a community's attitudes and move it to action.

Writing in the November 1964 Psychiatry, Dr. Robert Coles cites his clinical experience with about a score of veteran SNCC workers who had temporarily succumbed to what he calls "weariness and battle fatigue." Far from calling into question the judgment of these front-liners, Dr. Coles considers them and their colleagues "highly ethical and idealistic ... conscientious and steadfast." Moreover, on the basis of my own experience with another thirty-five or forty COFO workers, I am convinced that it is ridiculous to claim - as one of my colleagues is reported to have done in a recent lecture at the College - that their work is simply a search for identity and recognition. The quest for identity and recognition motivates most of us; it is not a sufficient explanation of why these youngsters have accepted a perilous, arduous, and frequently discouraging challenge. The contention also loses sight of the crucial point that many SNCC and COFO workers do have conventional plans and future ambitions but have consciously decided to defer them in order to help others find routes to self-realization. Finally, any such oversimplified statement fails to take account of the high degree of self-reliance and responsibility that are called for in moving into alien communities and in making decisions upon which the welfare of others can depend.

In this connection, a portion of Dr. Coles' description of the customary working environments of SNCC staff members is worth repeating here:

"The work of these students is not totally the action caught by cameras or reported in the news. The brunt of it is taking actual residence in towns where their goals are considered illegal at best and often seditious; considered so by local police and judges, by state police and judges, by business and political leaders. ... Most significantly, they are also feared, and resented, too, by their own kind, by Negroes as well as whites. The job of organizing Southern Negroes into effective groups for sustained assertion of their rights is a hard one. ... Negroes in Southern towns are heavily apathetic, widely illiterate, predominantly anxious, and afraid of any protest in their own behalf."

By now, more than a half-year since Coles' paper appeared, I think the last part of his description tells only part of the story. It seems more accurate to say that Negroes in Mississippi towns are less apathetic, and tend to be ambivalent rather than fearful about protests in their own behalf. True, they are more often than not afraid to be active participants themselves, but with good reason, since their jobs and their personal and familial welfare can actually be threatened if they are thought to be trouble-makers or if they are even suspected of "hangin' around with them damn agitators." Students, young people without families, others who are willing and free to postpone social mobility and economic security - these are the sorts of people who can take up the slack for the ambivalent ones.

There are towns in Mississippi where they have done so, where portions of Negro communities respond to their presence in an obviously warm way, where they win respect for their courage, and where there is a small but growing groundswell - at times almost clandestine — of moral and financial support for their activities. Not everyone knows that COFO workers depend on local community support and that their pay is only ten dollars a week.

6. Ideology and Image

Most civil rights workers in Mississippi probably could not continue without these bases for becoming involved in the communities where they work and for being accepted by the people who live in them. Still, the support is limited. For example, there probably is not a town in Mississippi where COFO has been able to win open aid and encouragement from the majority of the Negro middle class. Thus it is not surprising to discover that COFO people are impatient with better established, more prominent, and by far more cautious local Negro leaders. By the same token, it is not hard to understand why they conceive of Mississippi as dichotomized into a white ruling group on the one hand and a cowed and manipulated subordinate Negro group on the other, with the whole state and each of its towns run by a conspiratorial "white power structure."

This cynical view obviously inclines those who adopt it to make stereotyped assessments of white communities and white leaders. Nevertheless, it is important to see that it is not a point of revolutionary doctrine, and that it does have some justification. A sustaining defense, it helps COFO workers to account for their own activities, to explain why many white Mississippians do not speak out for change and remain silent in the face of campaigns of terror, and to interpret the caution that characterizes fearful though locally prestigious Negroes whose hard-won status and security hinges precariously on their remaining able to deal with paternalistic white men on the white men's terms. It also provides a rationale for assuming that the only major difference between middle-class members and non-members of Citizens' Councils is that those who don't belong are too shrewd to identify themselves with a group that supports segregation too openly and not always very cleverly. One encounters the same view in somewhat different form in the towns where COFO has been able to win some hard-wrung concessions. There one hears that the improvements in race relations did not stem as much from white good will as from town fathers' desires to maintain a favorable municipal reputation by avoiding trouble.

As for the justification of this perspective, consider that in Mississippi there is not yet a single white spokesman around whom other white liberals and moderates can openly rally. James Silver pointed out not long ago that Mississippi was a "closed society." It is still closed, even as its official leadership earnestly devotes itself to refurbishing the state's "image." (The term seems to appear daily in the Jackson press.)

Public relations and image-building may be too late now, for Mississippi has become vulnerable. It is obviously more sensitive to the presence of the Federal government, especially as its Negro population becomes more sophisticated in employing legal techniques in combination with repeated tests of new Federal legislation. Moreover, a national spotlight now shines on both Mississippi and Alabama. (Louisiana may not be far behind.) Racism in these states has by now been so well publicized that they have come to serve as scapegoats for what has been, in effect, the nation-wide scandal of neglecting the needs and aspirations of many Negro citizens all over the country.

Mississippi is also vulnerable because more of its white population is beginning to fear violence and disorder. There are white opinion leaders who continue to criticize COFO for playing on their worn nerves, but who are equally critical of the more violent and brutal members of their own ranks. The threat of anarchy, the threat to white lives and property, has probably begun to lead more white Mississippians to think of demanding better leaders who will recognize the futility of relying on old techniques of employing terror and force to maintain caste distinctions during periods of social change.

Ultimately, the gap in communications between the races will have to be closed. Hopefully there will be room for conciliation as well as for consolidating efforts by members of both races to drive wedges into the closed society. Meanwhile, although many different techniques will be employed in keeping up the pressure for change, a group like COFO working day in and day out for and with lower and working-class Mississippi Negroes can play an important role. COFO speaks for those who have few other spokesmen, trying to bring closer a time when all men can speak for themselves. * The Deep South in Transformation, University of Alabama Press, 1964, p. 139.

THE AUTHOR: Assistant Professor of Sociology Bernard E. Segal '55, also an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the Medical School, went to Mississippi in March to do research into the ideology and motivations of students participating in the civil rights movement. He also sought to accumulate first-hand observations for his race relations course. A third reason, and one which motivated Mrs. Segal to accompany her husband, was that the Segals "have been much involved in the civil rights movement from a distance, and both of us wanted to see Mississippi for ourselves to learn how we could be more helpful from as far away as Hanover." Mrs. Segal's expenses were met by the Segals, and Professor Segal's expenses were covered by the College's Public Affairs Center and the Filene Foundation. "Neither group is responsible for the tenor of my observations," Professor Segal notes. He disclaims "expert" status on the basis of his short trip and readily admits that he would not qualify as an unbiased observer, "though I have tried to call the shots as I saw them." He also notes that the people he saw at COFO offices had been in Mississippi since September, adding, "Whether volunteers who were there just for the summer or for the voter registration campaign last fall would have the same out- look and attitudes as those who have chosen to stay longer is a question I have no way of answering." Professor Segal earned his master's and doctor's degrees at Harvard.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

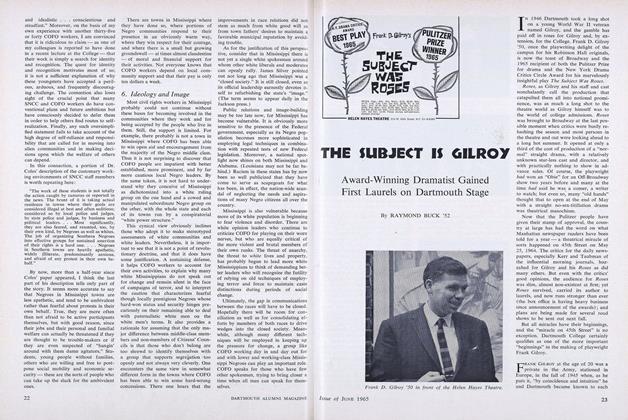

FeatureTHE SUBJECT IS GILROY

June 1965 By RAYMOND BUCK '52 -

Feature

FeatureSocial and Moral Responsibility in the Modern Corporation

June 1965 By RODMAN C. ROCKEFELLER '54 -

Feature

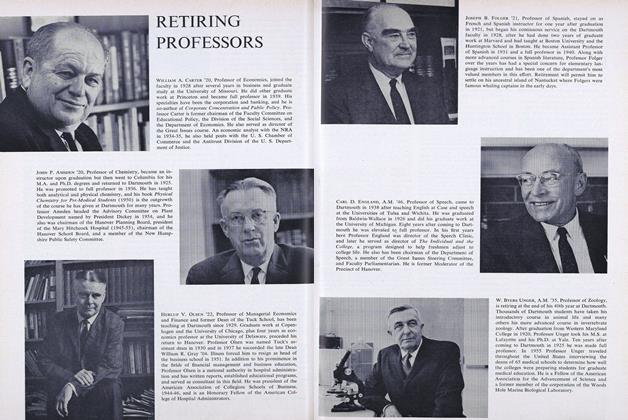

FeatureRETIRING PROFESSORS

June 1965 -

Article

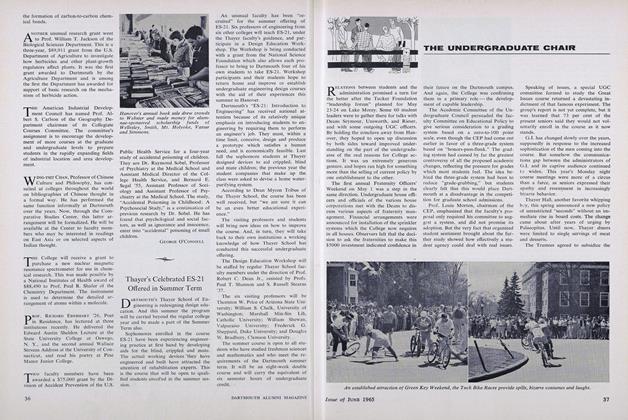

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

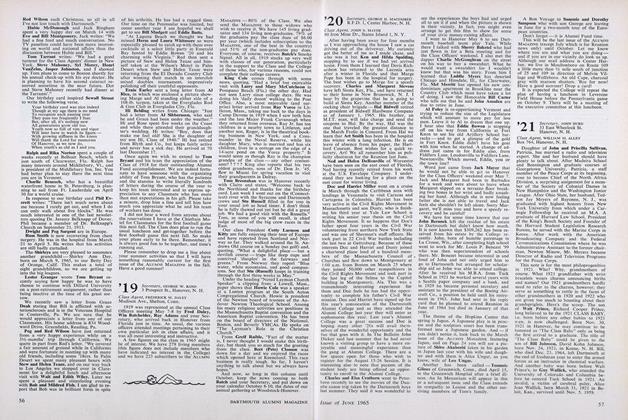

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

June 1965 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, JOHN S. MAYER

Features

-

Feature

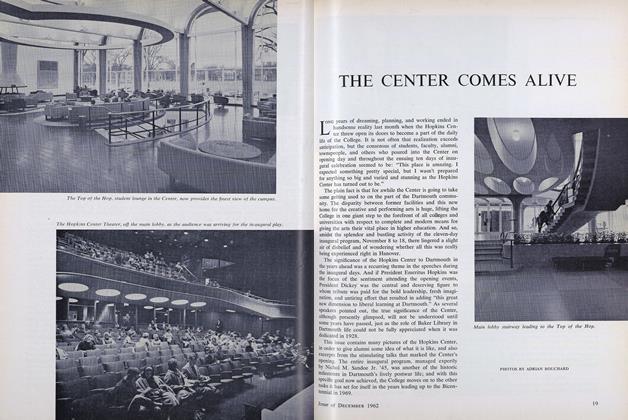

FeatureTHE CENTER COMES ALIVE

DECEMBER 1962 -

Features

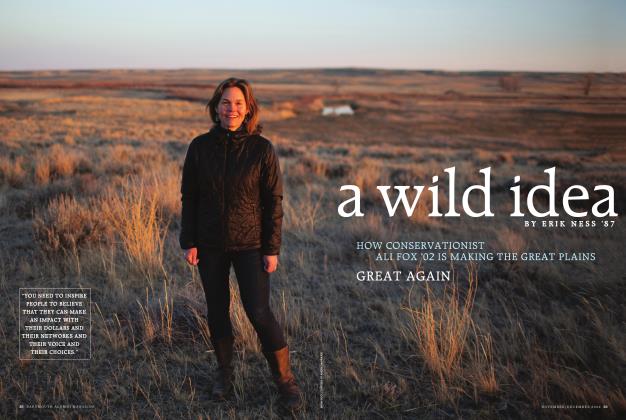

FeaturesA Wild Idea

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2022 -

Feature

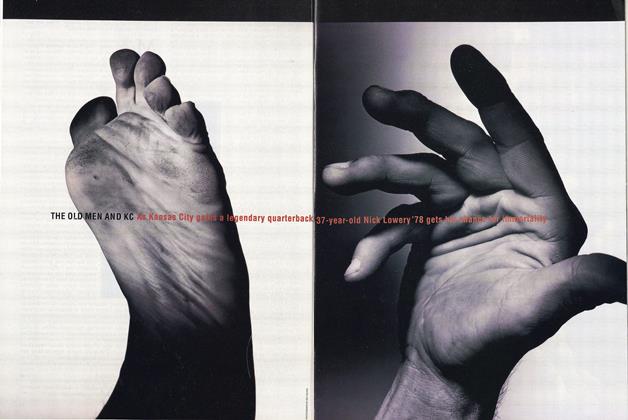

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

NOVEMBER 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDon't Call It "The D"

OCTOBER 1989 By Michael T. Reynolds '90 -

Feature

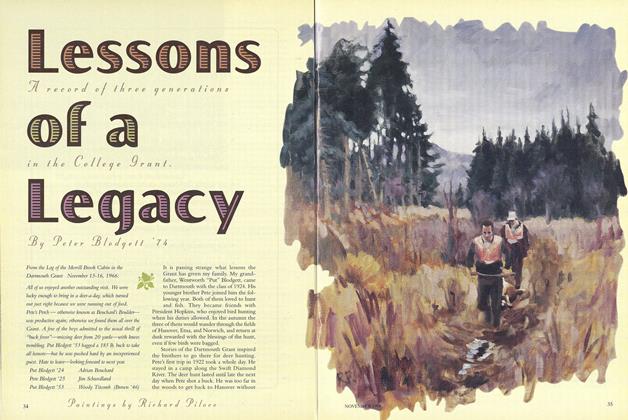

FeatureLessons of a Legacy

November 1994 By Peter Blodgett '74