An alumnus's caution eased the pains of the Filipinos' transition to democracy.

Stephen W. Bosworth '61 readily admits he never got on well with either Marcos when he was the United States' ambassador to the Philippines. He refused to be seduced by the Marcoses' flashy lifestyle, according to a recent book on the Philippines, Waltzing WithA Dictator: The Making of American Policy by former New York Times reporter Raymond Bonner. Once, Bonner writes, Imelda Marcos tried to coax the whitehaired, bespectacled Bosworth to sing at a state ceremony; after much resistance, the embarrassed ambassador cranked out "a few groaning noises that [were] a bit like music" evidence, according to Bonner, that Bosworth wasn't "dashing or flamboyant."

Rarely has a boring lifestyle been so useful in the conduct of foreign policy. When allegations of voter fraud in the Philippines led to massive street demonstrations last April, Bosworth had sufficient perspective to help engineer the Marcoses' removal.

A career diplomat, Bosworth has worked near some of the world's hot spots, including North Africa and Latin America. But his most celebrated experience was his stint in the Philippines from April 1984 to April of this year, when President Corazon Aquino took control. "Stephen W. Bosworth was the right man at the right time in the right place," writes Bonner. He was "a diplomat's diplomat: cautious; careful; always keeping his options open, protecting his flanks."

Even as the United States withdrew its support from his regime, the Filipino dictator clung to the presidency. "Marcos would have done anything he could have to stay in power," Bosworth noted recently. By carefully maneuvering among the Reagan administration, Aquino's advisors and the Marcoses, the ambassador smoothed the way for a relatively peaceful transition of power.

For all his acquired skill, he practically stumbled into the diplomacy business. Bosworth studied international relations at Dartmouth mainly because it allowed him to take a wide range of courses. Undecided about a career when he graduated in 1961, he hoped to buy time by attending law school. But he couldn't afford it, so he took the Foreign Service exam.

Some 25 years later, Bosworth knows enough of Filipino culture and politics to dismiss journalists' concerns about Aquino's ability to run the Philippines. "When they argue Aquino should have stood the leaders of past coup attempts up against the wall, they are ignoring that Filipinos, by nature, tend to be non-confrontational and risk-averse," he says. "Aquino has been following a policy with the military insurgents of gradually tightening the bonds of discipline."

Bosworth is concerned, however, that she is being forced to react "not necessarily to reality, but to the perception of reality, domestically and internationally." News commentators' tendency to offer advice and analysis based on inadequate information plays a significant role in molding that perception, he believes. "If Corazon came to me and said, 'Stephen, what should I do now about the coup leaders?' I would keep my mouth shut," Bosworth maintains. "Because I am not Filipino, I would not presume to advise her how to deal with other Filipinos."

Is the Philippines a model for American policy in other countries? Bosworth says the U.S. should support democracy, but "only to the extent that there is momentum toward democracy in the country itself. We can't, and shouldn't try, to write a national agenda for every one of these countries.

"I think Nicaragua is a tragic case," he continues, "because its revolution took too long, and I contrast it to the Philippines in that regard. By the time the dictator Anastasio Somoza fell in Nicaragua, the more moderate forces in the opposition had been overwhelmed by the extremists from the left, who also happen to own the guns." Nonetheless, Bosworth thinks the United States should devote more of its efforts toward a negotiated settlement of the country's civil war.

He says it is too early to judge how history will regard Reagan's overall foreign policy, and he has chosen not to evaluate the stands of the 1988 presidential candidates on foreign policy.

"One of the symptoms that led me to conclude I was probably ready to leave government," he admits, "was that I became consummately bored with discussions as to who was likely to become the next president of the United States."

At 48, the ambassador has left public life. From June through December he will be a John Sloan Dickey Fellow at Dartmouth, teaching classes, writing a book about his experiences in the Philippines and pondering what his next job will be. He said he has enjoyed his stay in Hanover, even though his penchant for caution doesn't always jibe with his students' desires.

"People here like answers," he says. "You give them a sort of considered, on-the-one-hand-but-on-the-other-hand kind of response, you can see that they're left with a certain sense of unfulfillment. Diplomats become much more aware of ambiguities and shades of gray, much less certain of their own judgment." Rich Barlow

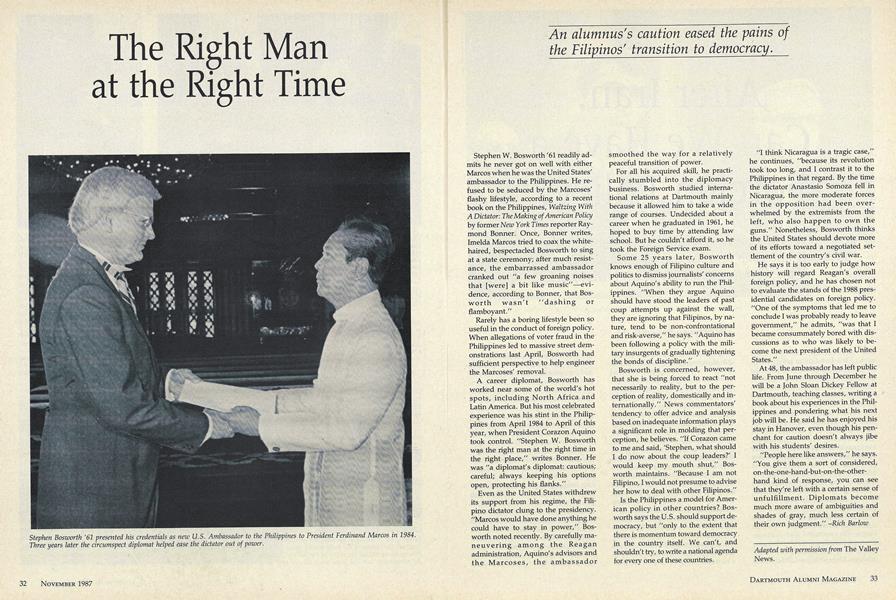

Stephen Bosworth '61 presented his credentials as new U.S. Ambassador to the Philippines to President Ferdinand Marcos in 1984.Three years later the circumspect diplomat helped ease the dictator out of power.

Adapted with permission from The Valley News.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

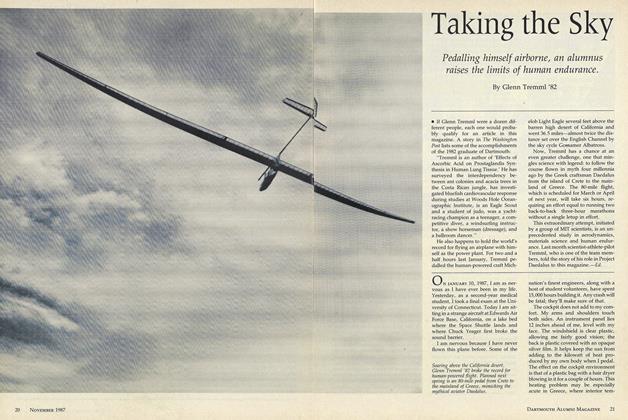

FeatureTaking the Sky

November 1987 By Glenn Tremml '82 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Iran: Can We Have a Foreign Policy?

November 1987 By Stephen Bosworth '61 -

Feature

FeatureAre Conservatives Being Silenced?

November 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

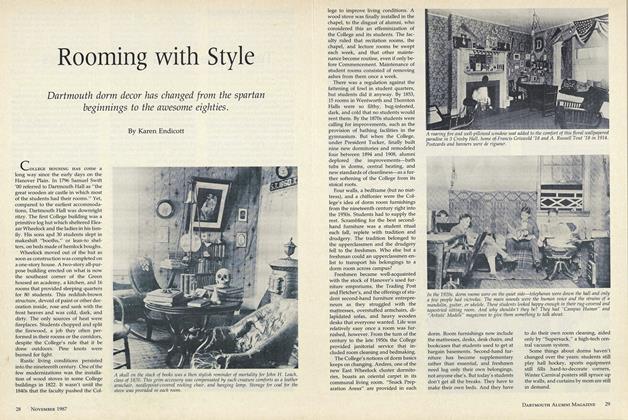

FeatureRooming with Style

November 1987 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

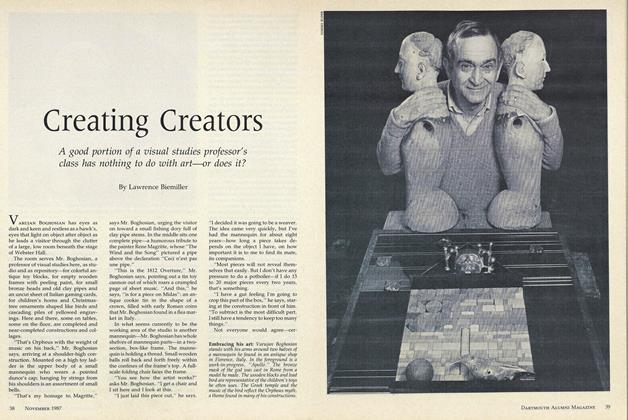

FeatureCreating Creators

November 1987 By Lawrence Biemiller -

Feature

FeatureTesting the Body's Competitiveness

November 1987 By Teri Allbright

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHEAR ON THE STREET

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

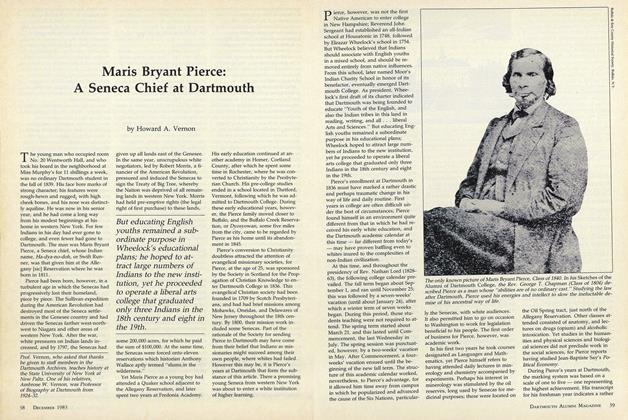

FeatureMaris Bryant Pierce: A Seneca Chief at Dartmouth

DECEMBER 1983 By Howard A. Vernon -

Feature

FeatureWhat's So New About It?

MAY 1973 By Joanna Sternick, A.M. '72 -

Feature

FeatureProps, Wingers, And Keepers Of The Old School

APRIL 1999 By Stuart Krohn -

Feature

FeatureBusiness as a Social Service

October 1956 By THE HON. RALPH E. FLANDERS, LL.D. '51, U.S. SENATOR FROM VERMONT -

Feature

FeaturePublic Policy: The Ordeal of Choices

JANUARY 1971 By William D. Carey