Following are excerpts from Jerold Wikoff's new book, The Upper Valley: an illustrated tour of life along the Connecticut River before the twentieth century. Dr. Wikoff, who taught in the history department at Dartmouth, published some of the chapters of his book earlier in different form in The Valley News. As his subtitle suggests, Prof. Wikoff's emphasis is visual rather than strictly historical. He is currently at work on a biography of the redoubtable John Ledyard, Class of 1796. The Upper Valley is published by Chelsea Green Pub. Cos. of Chelsea, Vt. Ed.

The drafting of New Hampshire's first constitution was a hasty affair. In October 1775 the colonial legislature asked for guidance from the Continental Congress "with respect to a method of our administering Justice and regulating our civil police ..." The Continental Congress responded in November, stating rather broadly that New Hampshire should "establish such a form of government . . . [which] will best produce the happiness of the people and most effectively secure peace and good order in the province." Receiving this advice, the colonial government formed a committee, which presented a constitution for acceptance on January 5, 1776. The legislature passed this constitution with no difficulties and subsequently called upon towns throughout New Hampshire to send representatives to the newly formed government. Now the trouble began.

Grafton County towns refused to accept the constitution or to send representatives to the new legislature. Much of their opposition lay in the fact thatowns were not represented individ- ually in the legislature. Being sparsely populated in comparison with the coastal part of New Hampshire, many Connecticut River towns were grouped together as a unit, each granted a single representative. This especially incensed the Grafton County towns, as it seemed to them that the royal government was not much different from the new one, "except that the Governor had the power in the former, and a number of persons in the latter." In neither case did towns in the Upper Valley feel they had any real representation. To rectify the matter, the Grafton County towns proposed "that every inhabited town have the liberty, if they please, of electing one member at least to make up the legislative body." This proposal corresponded to the Upper Valleinhabitants' belief that local town governments should have significant power.

At the center of the rebellion were the towns of Hanover and Lebanon, and it was Elisha Payne of Lebanon and Bezaleel Woodward and John Wheelock of Hanover who organized the growing protest. Officially, the rebellious group was called the United Committees. The "college party" was the more popular term, however, as several affiliated with Dartmouth College were influential in organizing the protest. Attempts were made by the Exeter government to mollify the Upper Valley towns, and in 1777 an offer was even made to convene a new constitutional convention. But it was too late. The rebellion had grown and its focus had shifted. Leaders of the United Committees no longer saw their goal as one of political representation within New Hampshire; they now desired something much larger the formation of a new political entity.

The rebellion continued to grow. In addition to their refusal to send representatives to the legislature in Exeter, the Upper Valley towns also withheld their tax quota from the New Hampshire government. By 1777 the United Committees had been successful in detaching almost forty towns from the Exeter government, and its next move was to attempt a union between these towns and the towns on the western side of the Connecticut River. Such a union, it was hoped, would lead to the formation of a new state called New Connecticut. A further hope was that the capital of this state would be the new town of Dresden, created from the corner of Hanover where Dartmouth College is still located. This attempt to make Dartmouth a political center became one of the primary goals of the rebellion.

The proposal to form the state of New Connecticut was immediately undercut. A second rebellion had developed in the territory west of the Connecticut River under the leadership of Ethan Allen, who sought independence from the claims of both New York and New Hampshire. His goal was to form a new state, "Vermont." Land speculation played a part in the rebellion's origin. Ethan Allen laid claim to over forty thousand acres of land most of it located in the Champlain Valley and his title was good only if New York claims were rendered invalid.

The Vermont rebellion overlapped with the Upper Valley one, since the new state of Vermont would include half of the proposed New Connecticut. Undaunted, the rebellious New Hampshire towns made no attempt to thwart the Vermont rebellion. Instead, they sought to join it by becoming a part of Vermont. When the first Vermont legislature met in Windsor on March 12, 1778, a delegation was sent to propose that Vermont accept into its union sixteen New Hampshire towns, as well as other towns that might be desirous of such a union.

By joining Vermont, "college party" leaders realized that Vermont's population would be concentrated in the Upper Valley. They then planned to propose that Dresden be made capital of the new state. If this plan failed, then all of Vermont might be made a part of New Hampshire. Dresden i.e., Dartmouth College with its central location in such an enlarged New Hampshire, would serve ideally as the state capital.

Ethan Allen and other Bennington leaders of the Vermont rebellion had no desire to see their power usurped by the Connecticut River towns, and they strongly opposed including New Hampshire towns in Vermont. Initially the Bennington party was outmaneuvered. Towns west of the Connecticut threatened to break from Vermont and form a new state with the towns across the river. To prevent such a move, sixteen New Hampshire towns Lyman, Gunthwaite (Lisbon), Morristown (Franconia), Bath, Landaff, Apthorpe (Littleton and Dalton), Haverhill, Piermont, Orford, Lyme, Hanover, Canaan, Cardigan (Orange), Lebanon, Enfield, and Cornish were admitted into Vermont on June 4, 1778.

Admission of these towns into Vermont solved nothing. Both rebellions continued throughout the Revolutionary War, as the Exeter government, the "college party," and the leaders in Bennington struggled with each other for political power. In the end the "college party" lost. Shortly after the sixteen New Hampshire towns were admitted into Vermont, Ethan Allen and his brother Ira maneuvered to rescind their admission. In retaliation, the "college party" organized a campaign to bring the entire Upper Valley into Vermont. They almost succeeded when, in 1781, Vermont annexed thirty-eight New Hampshire towns despite the Aliens' opposition.

This annexation, like the first, was short-lived, as the Continental Congress finally put an end to the continuing disputes and intrigues in the Upper Valley and Vermont. As a condition for acceptance as an independent state, Congress insisted that Vermont give up all claims to any territory east of the Connecticut River. Threats were also made, implying that if this condition were not met, New York and New Hampshire would be granted a common border along the ridge of the Green Mountains. In Bennington on February 23, 1782, the Vermont legislature voted to relinquish any claims east of the Connecticut River. To force the New Hampshire towns back into a union with the Exeter government, Congress also threatened in January 1782 to send troops to bring the rebellion to an end. This threat was sufficient to make most of the rebellious towns break with the "college party."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

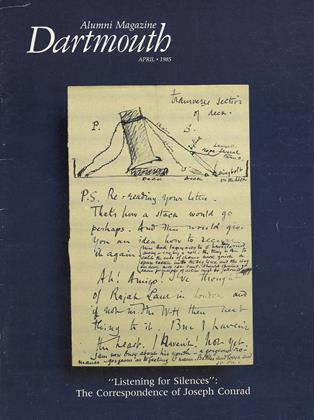

Cover StoryListening for the Silences

April 1985 By Laurence Davies -

Feature

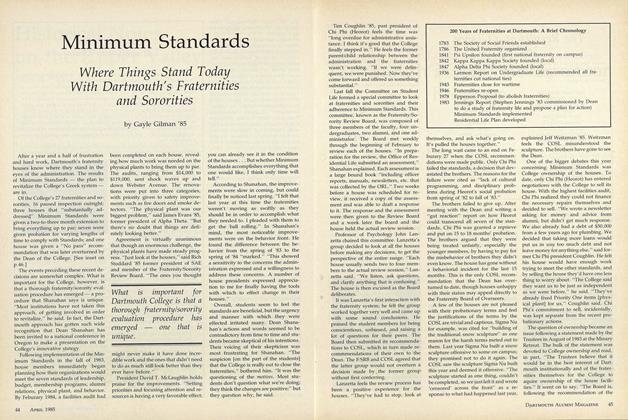

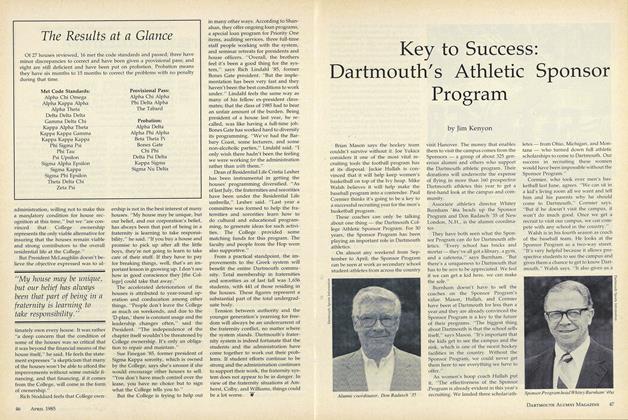

FeatureMinimum Standards

April 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Feature

FeatureKey to Success: Dartmouth's Athletic Sponsor Program

April 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureFROM THE DESK OF THE PRESIDENT

April 1985 -

Article

ArticleWorth his salt

April 1985 By JOseph Berman '86 -

Article

ArticleBud Brown '25: Happy trails keep him smiling

April 1985

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Plan

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Cover Story

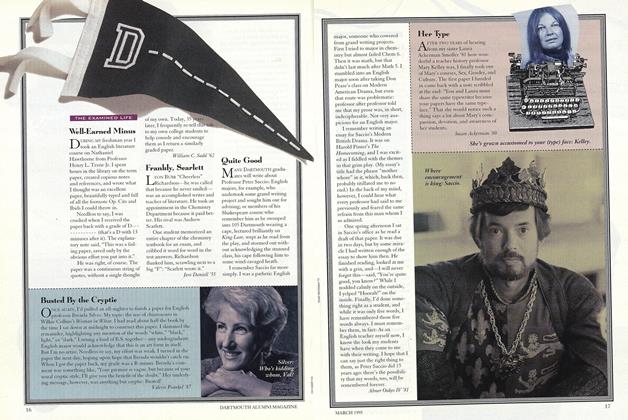

Cover StoryFrankly, Scarlett

MARCH 1995 By Jere Daniell '55 -

Feature

FeatureThe Best of The Old Farmer's Almanac

June 1992 By Judson Hale '55 -

Feature

FeatureWhere Are the Silver Cornets? or Twenty Versts to Nizhni Novgorod

By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Feature

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham