A ward-Winning Dramatist Gained First Laurels on Dartmouth Stage

IN 1946 Dartmouth took a long shot on a young World War II veteran named Gilroy, and the gamble has paid off in roses for Gilroy and, by extension, for the College. Frank D. Gilroy '50, once the playwriting delight of the campus for his Robinson Hall originals, is now the toast of Broadway and the 1965 recipient of both the Pulitzer Prize for drama and the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for his marvelously insightful play The Subject Was Roses.

Roses, as Gilroy and his staff and cast nonchalantly call the production that catapulted them all into national prominence, was as much a long shot to the theatre world as Gilroy himself was to the world of college admissions. Roses was brought to Broadway at the last possible moment when critics were busily rehashing the season and most persons in the theatre and out were looking ahead to a long hot summer. It opened at only a third of the cost of production of a "normal" straight drama, with a relatively unknown star-less cast and director, and with practically nothing to show in advance sales. Of course, the playwright had won an "Obie" for an Off-Broadway show two years before and many at the time had said he was a comer, a writer to watch; but even so, many "old hands" thought that to open at the end of May with a straight no-sex-titillation drama was theatrical masochism.

Now that the Pulitzer people have given their stamp of approval, the country at large has had the word on what Manhattan newspaper readers have been told for a year - a theatrical miracle of sorts happened on 45th Street on May 25, 1964. The critics for the daily newspapers, especially Kerr and Taubman of the influential morning journals, huzzahed for Gilroy and his Roses as did many others. But even with the critics' good opinions, the audience for Roses was slim, almost non-existent at first; yet Roses survived, carried its author to laurels, and now runs stronger than ever (the box office is having heavy business since announcement of the awards); and plans are being made for several road shows to be sent out next fall.

But all miracles have their beginnings, and the "miracle on 45th Street" is no exception. Dartmouth College certainly qualifies as one of the more important "beginnings" in the making of playwright Frank Gilroy.

FRANK GILROY at the age of 20 was a private in the Army, stationed in Europe, in the fall of 1945 when, as he puts it, "by coincidence and intuition" he and Dartmouth became known to each other. Before joining the Army in January 1944 Gilroy had completed studies at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx where his interests were many but his grades and related academic achievements were unexceptional. He also had a brief period at Juilliard School of Music where he decided, as he wrote in his application to Dartmouth, that "mediocrity doesn't pay so I relegated my musical interests to the position of an entertaining hobby."

The Army experience was good for Gilroy. "It gave me a new sense of values, men, and deeds to use as comparisons . . ." he wrote to Dartmouth. In the Army Gilroy also decided that he wanted to go to college and that he wanted to write.

In the fall of 1945 on a brief leave from Army duties, he met several Dartmouth alumni on the ski slopes in Austria. The alumni, as one might expect, whetted the Gilroy appetite for higher education, and especially for Dartmouth. Gilroy returned to his base and wrote his first letter to Dartmouth. The late Dean of Admissions Robert C. Strong '24 answered with what Gilroy recalls as a "very nice, hospitable, generous note."

Three or four more letters were written and answered. Gilroy also applied for admission into the College — he had applied to 40 or more other colleges and universities too. But he had a special feeling about Dartmouth, based in part on his correspondence with Dean Strong, and upon his discharge from the service in May 1946 he immediately took a train to Hanover - only to find that the man who had shown such interest in him had looked up Prof. Arthur Jensen in the English Department, a friend of a friend, and Jensen took him to see Edward Chamberlain '36, then acting Dean of Admissions. Gilroy recalls how he asserted his sense of having achieved a firm fix on life and how he stressed that he was looking for someone to take a chance.

He was well aware of the admissions pressures on the College that year - from its own students who had gone off to war and now wanted to return without delay and from others - even before the acting dean put the odds squarely before him. But Gilroy persisted. He submitted a short piece of prose fiction, an interesting piece titled "The Worn Out Wind- mill," through the alumni interviewer, author and editor Dave Camerer '37. This found approval with Camerer. "That a youngster, trying to impress someone with his writing," wrote Camerer to Chamberlain, "has seen fit to underwrite rather than overwrite - speaks volumes for the boy's sense of proportion."

Back in the Bronx the mailman did not make young Gilroy's first weeks at home any too pleasant. Rejection after rejecttion from colleges of all descriptions, north and south and west, came in; then finally there was an acceptance from Davis and Elkins College in West Virginia. At about mid-summer with rejections from all but Davis and Elkins - and about to make his plans for traveling to West Virginia - Gilroy received notice of his acceptance by Dartmouth.

However, about the time he had matriculated at Dartmouth and was settled in his dormitory room, Gilroy began to have his doubts about whether or not he could do the work expected of him. Fortunately his two roommates, Matt Cooney and Cal Minor, both Class of 1950, were veterans with similar doubts. "We made a vow," Gilroy recalls, "that we would never go to bed any night until all the work in the room was accomplished." The only time they gave themselves a recreation-break was on Sunday night, and then they splurged with dinner at the Inn.

FOR all his early doubts and the effort and time necessary to prove himself capable of Dartmouth work, Gilroy looks back on his first year as somehow "more personal, more satisfying, more exploratory." He signed on as a heeler on TheDartmouth and began writing short prose fiction for the literary magazine as he had done for the various Army journals that had given him his first taste of publication. But it was in the freshman English course with Prof. John Finch that he began to sense the joy of education. He was elated by the personal interest and encouragement from Professor Finch - and surprised and challenged when the paper that had gained him such an encouraging response was returned with a grade of C. "He was the first teacher I'd met who engaged my curiosity," Gilroy noted. "I was receptive. I responded to him. English I was very important to me beyond the contents of the course."

Gilroy kept at his writing, news pieces for The Dartmouth, where he was spending an increasing portion of his time, and prose fiction for The Quarterly, but it wasn't until his junior year when he enrolled in Prof. Ernest Bradlee Watson's course in playwriting that what was to be his real forte entered his life. "I had not only never written a play, I'd only seen a couple," noted Gilroy, "but I found myself in that class. What I was striving for didn't seem to be coming out in prose, but I could feel the very best that I could do coming out in the dramatic form."

And Gilroy's first efforts in the dramatic form were very good indeed, so good in fact that Prof. Henry B. Williams, Director of the College's Experimental Theatre, can recall vividly the day that Professor Watson came into his office with a script of Gilroy's first fulllength play in his hand. "This is a play we ought to do," Professor Williams remembers Watson as saying. "This was a very productive period in writing," Williams notes; "the veterans had a lot to say. There were lots of full-length plays being written on campus." But both he and Professor Watson thought the Gilroy script was "terribly imaginative."

As they moved into the production of the script, The Middle World, in which Gilroy also acted, Williams remembers that he told Gilroy there probably would be many changes to make in production. "I want you here at every rehearsal," Professor Williams, the play's director, told the playwright. On the night of the second rehearsal Gilroy didn't show up until after ten o'clock. Williams recalls that he lit into the young playwright. "I'm terribly sorry," Gilroy is reported to have said and as explanation he offered, "I've just been made Editor of The Dartmouth." But despite the editorial responsibilities that came with that honor — and the time-consuming Palaeopitus and UGC committee work that went along with it, Gilroy stayed right with the production. "He was excellent at script changes," Williams recalls.

The Middle World was awarded first- place honors in the Eleanor Frost Prize Play Contest for 1948-49 and a Gilroy one-act script, McClintock's .Medal, was the choice for third place. The latter script also .won a third-place prize among 212 entries in a nationwide play writing contest sponsored by the Valparaiso (Ind.) University Players.

The Eleanor Frost contest for 1949-50 was another all-Gilroy affair with his fulllength play The Great Art taking first honors and his shorter piece A Messageto the Ants from Willie as runner-up. The latter script submitted to a CBS Awards competition to discover new television dramatists in American colleges and universities won a tie for first honors for the fledgling Dartmouth playwright.

In addition to his two three-act and two one-act shows in Frost competition, Gilroy had six other one-acters presented in Robinson Hall - for the most part in the interfraternity play competition. Warner Bentley, Director of the Hopkins Center, remembers that with the daily newspaper, the Quarterly, and his plays, Gilroy was around Robinson Hall almost as much as he himself was from the spring of 1949 to commencement time in 1950.

"It was pretty evident in all those plays that Frank had a real talent for writing dialogue that is meaningful, easy to say, and completely in character," Bentley stated recently. "This was one of the talents the late Robert Sherwood had too."

Bentley went on in his reminiscences. "Frank was serious about his work but with a great sense of humor about himself and other things. He was an interesting guy to work with. He was fascinated with dixieland."

The one-time Juilliard music student had not forgotten his trumpet when he came to Dartmouth. One of his major diversions from the pressures of newspaper editing and dramatic production - not to mention his academic work which resulted in graduating with honors as a sociology major - was to get into a good hot dixieland jam session. Although a member of Theta Chi fraternity, Gilroy was just too busy on other parts of the campus to be very active in fraternal affairs. In fact, one younger brother recalls, Frank Gilroy was "that guy we always bragged about but never saw except on big weekends when he was playing his trumpet with the band in the living room while keeping one eye on the beautiful blonde model he'd brought up from New York." Of such remembrances are legends created.

But the horn did play a big part in Gilroy's creative thinking. The GreatArt, for instance, had a hero who was a trumpet player. In fact both Williams and Bentley remarked there were two things that always seemed to be associated with Gilroy's undergraduate shows: a trumpet and a refrigerator.

"The Phoenix curtain went up on Who'll Save the Plowboy?" Henry Williams said, "and in the background was the sound of a trumpet. 'All is well,' I said to myself and I settled back to enjoy that marvelous show." Warner Bentley had the same reaction when he saw the refrigerator almost center stage as the opening night curtain revealed the set for Roses. There is no trumpet player in Roses, however.

GILROY was highly recommended by everyone connected with Dartmouth dramatics for a Dartmouth fellowship so that he might continue his studies in play writing at Yale University School of Drama. "I remember writing in my recommendation at the time," Director Bentley recalls, "that I was very sure that at some time Dartmouth was going to be very proud of Frank Gilroy."

Gilroy was awarded the Dartmouth fellowship, but before he enrolled at Yale he spent the summer playing in nightspots with a jazz band made up of fellow Dartmouth musicians. He had some lingering thoughts that he could be a jazz musician. "That summer I discovered I didn't have the talent or inclination for that," Gilroy recently said, and that decision moved him farther into the commitment to his writing. "Going to Yale offered me time, another year, to write, to live in a continuous atmosphere of discussion of theatre," Gilroy remembers, but after he'd been there a short while he dropped all his course work except what was offered in playwriting. "Yale Drama was a good place to be if you had something to write," Gilroy said, but he knew it wasn't the place for him. He wanted - and had — to make a living.

After a few "odds and ends" type of jobs Gilroy broke into television and took the first step toward establishing himself as a free-lance writer. Some dialogue "sketches" impressed literary agent Blanche Gaines, and she went to work in Gilroy's behalf — and is still at it. A ten-minute sketch was sold to the Kate Smith Show, and Gilroy was on his way. The next year he began selling half-hour shows. Television drama was live, and alive, then. Knowledge of camera techniques and other technical matters didn't seem to matter, Gilroy recalls wryly. "All one needed was a responsible estimate of what was possible and not possible."

By 1954 Gilroy was a TV writer with credits galore. His scripts were being seen on those oft-recalled, hour-long shows of the mid-fifties - the Kraft TV Theatre, Studio One, U.S. Steel Hour - that gave opportunities to such writers as Paddy Chayefsky, Gore Vidal, Horton Foote, and so many others as well as Gilroy. TV's "Golden Age," a description Gilroy winces at, was good for Gilroy. Not only did it keep him writing but one show in particular, a U.S. Steel Hour, provided the funds for him to marry the attractive Miss Ruth Gaydos of Carteret, N. J., and to take a honeymoon in Florida.

This was a good move too. Marriage provided Gilroy not only with a lovely wife and companion - and future mother of his three sturdy sons - but a diligent business manager and what Gilroy has described as "one hell of an editor." Ruth, Gilroy readily states, is one of the first people he turns to for evaluation once he has gotten a solid first draft on a new script. "We don't always agree," Gilroy noted in a question-and-answer article in The Playbill for Roses, "but her judg- ment is very good."

Gilroy didn't write any plays for five years after he left Yale in 1951, but the desire to write his plays never left him. In 1957 with 40 to 50 TV scripts to his credit, including an original Western called The Last Notch which was described by the New York Times' TV critic "as very possibly the finest Western play yet done by 'live' television" (subsequently purchased for a movie by Hollywood), Gilroy decided he could take the time to do some writing for the stage.

He wrote both a long one-acter and a short one-acter before the full-length script later to be produced as Who'llSave the Plowboy? came along to occupy his complete attention. When the Plowboy script was finished in January 1958 and sent off to producers, Gilroy was "broke again," he recalls. He looked to television again but the TV drama industry had moved from New York City to Hollywood. There was no choice except to go west with it. "I went out to California in the spring of 1958 for a four-month stay," Gilroy remembers, "and stayed until the summer of 1962. It was a good move. I wrote Roses out there."

In addition to more television scripts Gilroy also wrote the screenplay for TheGallant Hours, a film about the late Fleet Admiral William F. "Bull" Halsey, among other film writing assignments. Film critic Bosley Crowther of The NewYork Times described the Halsey film as "drama of intense restraint and power ... one of the most manly biographies we have had."

MEANWHILE Who'll Save the Plowboy? was going the rounds in New York, being read and rejected by many people connected with the commercial theatre. Curiously enough, Gilroy told a reporter, "the script always seemed to appeal to directors. Producers were a bit leary of it. Probably because the theme was not the sort that would interest everyone."

Who'll Save the Plowboy? opened at Off-Broadway's Phoenix Theatre in 1962, four years after Gilroy had written it, for what was supposed to be a brief threeweek run, but the critics and audiences alike gave it such favorable notices that it was moved to another Off-Broadway theatre to keep it going. This is what Howard Taubman of The Times had to say about Gilroy's first New York offering: "With Who'll Save the Plowboy? the Phoenix Theatre Tuesday night introduced a new playwright, Frank D. Gilroy, with a gift for the stage. Who'llSave the Plowboy? has a number of striking merits. Its writing is lean, incisive, neatly adjusted to its characters and subject. Its characters, especially its three main ones, are sharply observed and sensitively realized. Its construction has economy and discipline. Mr. Gilroy knows exactly what he is about."

With such an auspicious entry into the commercial theatre, despite the fact that it was off rather than on Broadway, many were predicting an easy road ahead for Gilroy when it came time for him to offer his next dramatic script for production. Gilroy returned to California; then in the summer of 1962 - with Roses now in the hands of his agent - he returned to the East with his family.

On July 1, 1962 The Subject WasRoses was optioned for Broadway production. On October 16 of that year Gilroy began a daily journal on the trials and triumphs of bringing his script to Broadway. That diary was to cover a period of almost two years. It is now printed under the title About Those Rosesor How Not to Do a Play and Succeed as a curtain-raiser to Random House's publication of the Roses script. Paine Knickerbocker '33, drama critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, has written a review of that book which appears in the "Dartmouth Authors" department of this issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE and which outlines Gilroy's published story - there's more than enough to get the idea, but a reading of the full journal, and the play, is recommended.

It will be sufficient to say here that getting Roses to Broadway was an extremely challenging project and one in which the playwright played a much more active role than playwrights are expected or accustomed to play in the commercial theatre. Gilroy was not only instrumental in the selection of Jack Albertson as the pivotal lead character of the father, and Ulu Grosbard as the director, and Edgar Lansbury as producerdesigner; he also became a fund raiser to gather in a sizable portion of the money needed to put Roses on stage. Two of Gilroy's personal angels were Dartmouth classmates, Boston lawyer Dan Featherston and University of Maine college professor Dave Fink, and both figure prominently in Gilroy's journal.

The upshot of the production as it evolved was that the playwright had a billing equal to all others - a circumstance that is rather an oddity in contemporary American theatre and especially for a writer in his first Broadway outing. Roses belonged to Frank D. Gilroy, playwright, and not to some superstar, or super-director, or super-producer.

Dan Featherston and Dave Fink and the Henry Williamses and the Warner Bentleys were in the Royale Theatre on the night of May 25, 1964 when the formal opening night of The Subject WasRoses was celebrated. They all saw and heard and were deeply moved, but in the tradition of the commercial stage they were as uncertain as Gilroy was himself when they all gathered together at Sardi's afterwards for the inevitable "death watch." How would the critics react?

Henry Williams remembers the occasion. "Each of the cast entered Sardi's to great applause. Frank came in. No applause. Nobody knew who he was. The first report came in. A TV commentator had used the word banal. Spirits fell. Then a woman entered. 'What's everyone so depressed for?' she inquired in amazement. Someone told her. 'But haven't you read Kerr?' she asked. 'He says it's the best play of the year.' Frank turned to his wife and said 'I may have to marry this woman.' "

Gilroy had words for another lady too. At Gilroy's Dartmouth graduation Warner Bentley's wife Kit had told the young playwright that she was giving him ten years and before that time was up she wanted to be invited to the opening of his play on Broadway. On the opening night of Roses, Gilroy greeted her with "I was four years late." Mrs. Bentley didn't mind at all.

NEXT fall Roses goes on the road across the country. Like Plowboy which has been translated and played in Denmark, England, Poland, and six other countries, Roses also will be internationally produced - first in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Roses is now in the black, according to an article in the entertainment trade journal Variety, but it took 43 weeks and a payment of $25,000 for shifting theatres to do so. For Gilroy royalties have totaled more than $30,000 (as of the April 7 Variety article) and may be expected to move much higher with the help of the Pulitzer Prize and Drama Critics Circle Award bringing in the audiences in New York, on the road, and overseas. Although this may seem impressively high to the average theatre-goer, a comparison of Gilroy's earnings with those of Neil Simon for The Odd Couple, for instance, would illustrate the marked difference in the pulling power of sensitive drama in New York City as compared with "hit" comedy. Simon comes close to earning Gilroy's total yield in several weeks of full-house audiences.

"The play hasn't been a gold mine," Gilroy said to a reporter for the NewYork Herald-Tribune. "That's very obvious. I wouldn't want to evaluate it in financial terms. Twenty years from now I won't remember the grosses or what I made out of it. But for every one of us this has been one of the most glowing and satisfying experiences."

And speaking for one of thousands who have sat out front to experience Roses, this writer adds this personal commentary: the play glowed and was every bit as satisfying to this member of the audience too - and will be remembered for just as long. Roses is an exquisite moment in human pride and pain and love and awareness skillfully revealed by a master craftsman of the theatre.

Certainly Roses is strongly autobiographical. In his diary, in many things Gilroy says about the script, there is no •doubt that the created spirits of the playwright himself and his mother and father walk the stage of the Helen Hayes Theatre these nights. Gilroy has said that the story did not actually happen and that it took him twenty years to understand all that it was based on. But the fact that Roses is autobiographical in greater or lesser part really doesn't matter (except perhaps to those who may have known Gilroy's now deceased parents); what matters is the artistry with which Gilroy made this poignant moment of love and anguish come alive.

In his rented, phone-less office in Goshen, N. Y., ten miles away from his rambling onetime farm home in Monroe, N. Y., Gilroy is at work on another drama. He works slowly, rewriting as he goes along, fashioning each piece of his play to his satisfaction. "It's like building a house," Gilroy wrote for the Roses'Playbill, "I can't go on to the next floor until the one below it is right. The line of a play is such a fragile thing that if you make one mistake you go off."

These days because of awards and a strong desire to do whatever he can to boost attendance at Roses, Gilroy spends a good deal of time in New York City talking to groups and being interviewed. "You get addicted to talking about yourself," he remarks, "and sometimes pretty sick about it." Gilroy hasn't done any screen or TV writing since the opening of Roses; the future he sees is in the theatre.

But what type of a theatre does the future offer? Gilroy looks for a theatre that will accept and support all types of drama. The situation this spring with only two straight dramas, Roses and Edward Albee's Tiny Alice, is bad, Gilroy thinks. Broadway needs a broader base, lower prices, but most importantly, Gilroy believes, someone to step in and break the chain of boom-or-bust theatre. "No one makes money when theatres are dark," Gilroy adds. "Producers must think in terms of a modest return. They should observe the lesson that every farmer knows - you've got to put something back into the soil."

Gilroy, Edgar Lansbury, Ulu Grosbard, and the others associated with the Roses company have taken a giant stride in demonstrating that quality and not surface gloss can make the difference - and more importantly can find a supporting audience. And perhaps more impressively for the future of American theatre, they have established the playwright - in this case Frank Gilroy - firmly at the head of the joint creative enterprise that is the theatre production.

With the quiet assurance of a man who has sought and reached a major goal, Gilroy recalled with some amusement and wonder a recent conversation with a classmate from his high school days who stated that even then it was evident that Gilroy would be a writer. "I didn't write then, in high school, but I've always had the impulse to tell stories. Even if I hadn't gone to college, in some way I think I would have become a writer."

That's probably true, but it's also quite likely that it might have taken a lot longer - or perhaps taken a different form —if it hadn't been for the encouragement and opportunity to try out his dramatic wings at Dartmouth. That is illustrated best by Gilroy's own comments on the education of the writer: "I don't think that the teacher can supply something that doesn't exist, but the teacher can explore the full potential. He can bring out the best in the beginning writer."

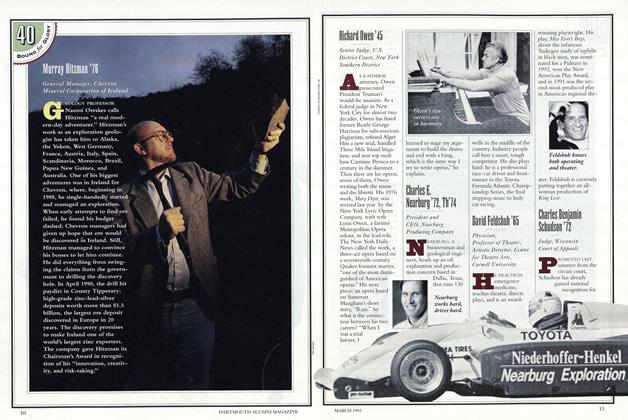

Frank D. Gilroy '50 in front of the Helen Hayes Theatre.

A scene from "The Middle World," Frank Gilroy's first full-length drama.

"The Great Art," presented in Gilroy's senior year, also won Frost competition.

The mother, Irene Dailey, is about tocast the symbolic roses at the feet ofthe father, Jack Albertson, in a scenefrom Gilroy's "The Subject Was Roses."

Roses were in bloom for this rehearsal discussion between the playwright (r) and hisfull cast, consisting of (l to r) Irene Dailey, Martin Sheen, and Jack Albertson.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStudents and Commitment in the Deep South

June 1965 By BERNARD E. SEGAL '55, -

Feature

FeatureSocial and Moral Responsibility in the Modern Corporation

June 1965 By RODMAN C. ROCKEFELLER '54 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING PROFESSORS

June 1965 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

June 1965 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, JOHN S. MAYER

RAYMOND BUCK '52

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDavid Feldshuh '65

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1951 By ALLAN NEVINS -

Feature

FeatureCollege Staff Members Reach Retirement

JULY 1972 By J.D. -

Feature

FeatureEight Graduates of Dartmouth Who Were First College Presidents

JUNE 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureLove and War Among the Ivies

Jan/Feb 1981 By Keith Bellows -

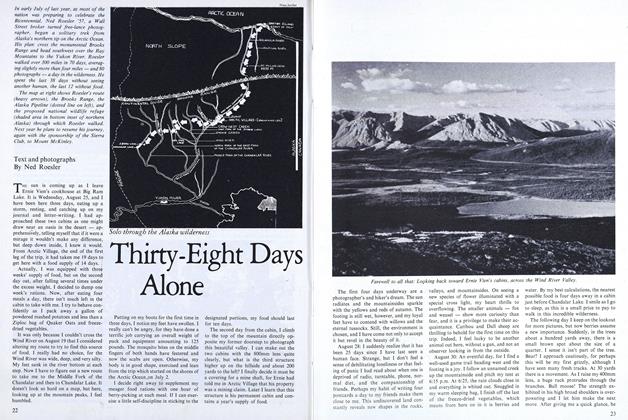

Feature

FeatureThirty-Eight Days Alone

SEPT. 1977 By Ned Roesler