TO THE EDITOR:

The July issue of this magazine contained an article by Professor Richard Sterling adapted from his remarks at a Viet Nam symposium held on campus last May. I also participated in the symposium; then, and again on reading the article, I liked very much some of the things he had to say and disagreed strongly with others. Since several points of view were represented at the symposium, it may be in order to offer some more discussion here.

The article appeared on two facing pages, and was divided in such a way that I agree with just about everything on the first page, which mostly states general ideas and outlines the problem, while I disagree with many of the conclusions that follow on page two. The last complete sentence in the first part of the article read "I would say again that if we cannot demonstrate satisfactorily that what we are doing in Viet Nam also serves the interest of the Vietnamese people, we'd better get out." It must be Professor Sterling's opinion, since he doesn't advocate getting out, that we are indeed serving their interest. This is something which, unfortunately, I cannot believe.

The heart of his case is, I think, fairly summarized by one sentence from the article: "We would [by leaving] be turning over the Vietnamese to a tyranny far more ruthless than the admittedly unlovely series of governments which have so far ruled in Saigon." There is certainly an element of truth in this. That North Viet Nam's government is in many respects a tyranny, and that it is more efficient if not necessarily more ruthless than that of Ngo Dinh Diem and his successors, is, I think, undeniable. But these facts are not enough to show that we are helping the people of Viet Nam by continuing the war in that country. To judge that question we must also consider the desirability of the alternatives to communist government, and the price which must be paid for war.

What sort of "great society" might be created in South Viet Nam with our help? I can find no good answer in recent history or in our policies. I think the evidence is pretty clear that Diem's government was, in the quality of its legal foundations, its dedication to freedom and the excellence of its communication with the bulk of its people, very little better than the communist regime in the North. The various military leaders who have succeeded Diem and each other have in these respects followed suit. The United States attitude has been fairly consistent too: although many regrettable things occurred, the objections we might have felt could not be pressed for fear of interfering with the anti-communist effort. This caution has been to some extent selfdefeating, and unquestionably one result has been that the Saigon government has enjoyed very little popularity and support from most of the country people whose interests we are supposed to be serving.

Recently many of our own actions have probably been hard for a villager to recognize as to his benefit. If an area is thought to contain a number of guerrillas, if a village - perhaps not voluntarily - supplies them with food and shelter, massive air attacks are likely to follow. The bombs we drop are remarkably insensitive to the politics, age or sex of the people below. And yet some, at least, of those people are not the "enemy" but our friends for whose benefit we are fighting. When we burn a village ourselves (a "Viet Cong village," to be sure, which means one located in an area government forces do not usually control) or acquiesce in the torture of prisoners, I wonder if our benevolent intentions are being clearly communicated to the Vietnamese people.

I think there is a definite conclusion to all this; that the best way to serve the interests of the people is to end the war. Professor Sterling is of course right that there are problems both practical and moral in this course, as there are in continuing or enlarging the fighting. The choice is between evils; no entirely good course of action is at hand. It is of course also true that any action has worldwide repercussions. He did not consider this aspect in detail, and neither will I except to state my belief that on balance the American national interest would be served best by making peace - the indirect effects of our Viet Nam efforts are almost all bad ones. It seems fairly clear that the start of peace negotiations could be at hand, if the United States really wants them and is prepared to compromise. We have been pursuing that "position of strength" too long already.

Professor Sterling said that in international affairs the real enemy is "alien tyranny," of which communism is the chief embodiment. I think the word alien ought to be deleted; tyranny is the enemy. It may come from communism certainly. It may come from famine or disease. It may come from non-communist governments - even, conceivably, our own. But one of the most absolute of tyrannies is that of war - and in Viet Nam I believe that it is the war itself which has become the greatest evil and the chief enemy.

Hanover, N. H.Associate Professorof Mathematics

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

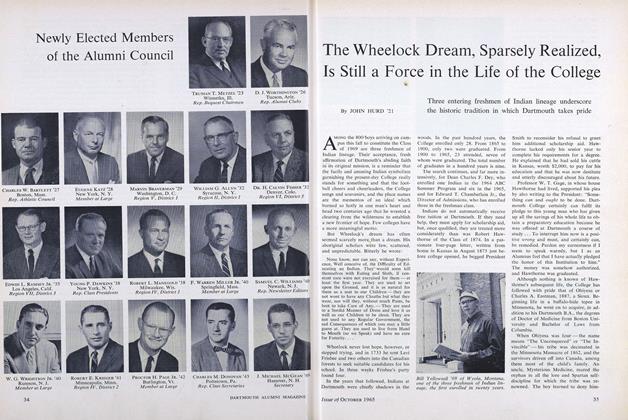

FeatureThe Wheelock Dream, Sparsely Realized, Is Still a Force in the Life of the College

October 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureA Good Summer Press

October 1965 -

Feature

FeatureSUMMER TEMPO IS GO-GO-GO

October 1965 -

Feature

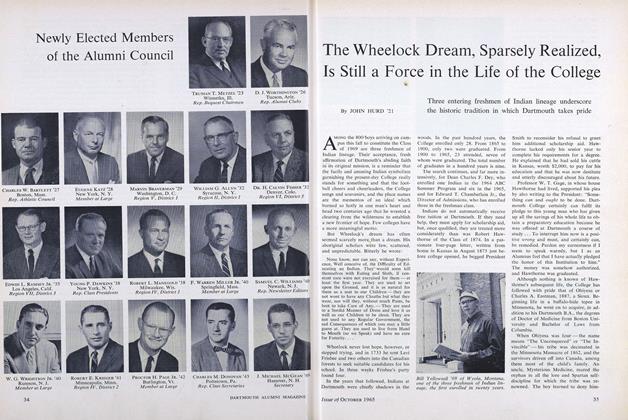

FeatureNewly Elected Members of the Alumni Council

October 1965 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleHow the "Big" Was Added to Green

October 1965 By W. HUSTON LILLARD '05

JOHN LAMPERTI

Article

-

Article

ArticlePresidential Grandson

January 1941 -

Article

ArticleWinter Recap

APRIL 1997 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January, 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleAllan Macdonald

January 1952 By ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Article

ArticleCeltic With a Bard "C"

NOVEMBER 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleConnecticut

June 1938 By Mansfield D. Sprague '33.