"This Is Not Enough"

TO THE EDITOR:

I read with interest Dr. Roderick Nash's rejoinder (Crusades for Crusaders, October issue) to Professor Bernard Segal's earlier piece on student commitment to the civil rights movement. At the risk of adding to what is somewhat of a tempest in a teapot, I am moved to say first that, except for Segal's distorted reference to what Dr. Nash said in a lecture, I found the Segal article a perceptive job of reporting and analysis.

What is disappointing about Dr. Nash's reply is the sense of incompleteness one is left with. His point is clear enough: student motivation in becoming active in the press altruism and with the wish to satisfy personal social psychological needs. I do not think the mature worker will agree with such a neat 50-50 division. At any rate, Dr. Nash then goes on to substantiate his position with a brief interpretation of the his- tory of abolitionism, and closes with a plea that we stop regarding rights workers as "saints." This is not enough.

I wish Dr. Nash had chosen a higher hilltop. After all, the greater significance behind American abolitionism lies not in the motivations of those responsible men and women who have embraced it, but rather in the efficacy of its works. Who cares that Jane Addams was pigeon-toed? There likely is no such person as a saint or an altruist, but surely there are altruistic — to stretch the meaning a bit - acts. We are currently witnessing such acts in the civil rights struggle by Dartmouth students (which heartens me enormously) as well as by many other college students. The eventual result will be the American Negro's achieving what should have been granted him from the beginning, equality.

Hampton Falls, N. H.

"More Than a Little Saintliness"

TO THE EDITOR:

Mr. Nash's rejoinder to Professor Segal, "Crusades for Crusaders," in the October issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE is an interesting and well-written piece and, for its length, well enough documented. I believe, however, that Mr. Nash employs at best an extremely naive theory of human behavior in supporting his case that "the freedom worker is as much concerned about satisfying his own personal needs as he is with helping the Negro." Indeed, his discussion of motivation can be seen to be (1) tautological, (2) deterministic, or (3) simplistic.

First the tautological error. Mr. Nash begins innocently enough when he explains abolitionism (or civil rights) "as a means of filling a psychological need." In this form, we have a valid and testable theory. All that is required is the set of needs which civil rights presumably fills. We then can independently classify people with respect to these needs and observe if they do or do not enter the movement, thus either verifying or refuting the hypothesis. Of course, when we see the characteristics Mr. Nash ascribes to the potential freedom worker - sensitive, thoughtful, concerned for identity and the meaning of life, craving action and commitment — we may well wonder why at least 50% of the undergraduate body of the College has not long since left for Alabama (leaving the insensitive, unthinking, etc. behind), but that actually is irrelevant. The fact remains that the theory of human behavior advanced or implied is capable of verification.

The tautological error arises when Mr. Nash states that "the crucial factor in precipitating the anti-slavery crusade was the development of men and women who wanted to be abolitionists." The need here is specific to the act, and in this form the theory is tautological. The freedom worker is in the civil rights movement because he needs to be in the civil rights movement. Obviously, if he didn't need to be, he wouldn't be there. Here there are no selfless actions, no altruism, not because such are found to not exist, but by definition. In this form, of course, the theory is incapable of verification and, in fact, is no theory at all.

The deterministic approach has man driven by needs sociologically or psychologically given to him, with no free choice entering into his actions whatever. Here we would find the picture of a member of the "sneakers-and-beard set," "notebook in hand," impelled willy-nilly to the cause of civil rights by deep subconscious needs over which he has no control. Although, perhaps, consistent as a system, this interpretation would deny man's essentially free nature and, indeed, would throw the Viola Gregg Liuzzos and the Lester Maddoxes all in the same pot. In this system, altruism can not exist because men can not choose of their own volition to act in a selfless manner.

If, certainly subject to the constraints of our subjective and often subconscious needs, we have free choice at all, it is in the expression of these needs, or in the means of filling these needs. Here is where Mr. Nash's argument becomes simplistic. Professor Segal, a sociologist, can hardly be held to believe either that civil rights workers do not have needs or that civil rights work fails to fulfill needs. The essential question, and one that Mr. Nash never raises, is why were the needs fulfilled in this particular way? If we are not determinists, we must answer: because the individual civil rights worker chose this way or because he chose to affirm his own individuality in this manner. In this system, altruism is possible because individuals may choose to act selflessly or not. It is, in the end, man's actions that we must evaluate, and those who constantly put their own lives in danger for the purpose of helping others have more than a little saintliness about them.

Department of Economics

Hanover, N. H.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

November 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44, -

Feature

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

November 1965 -

Feature

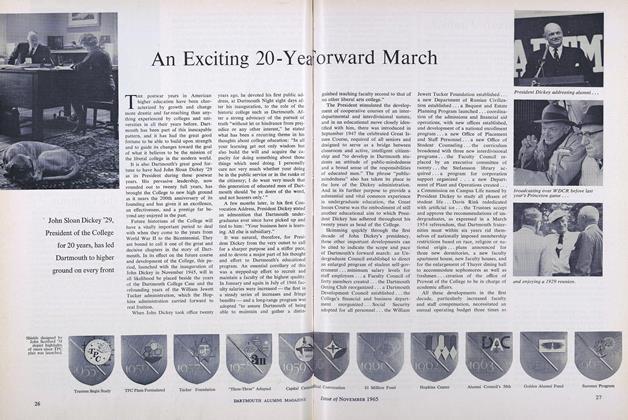

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

November 1965 -

Feature

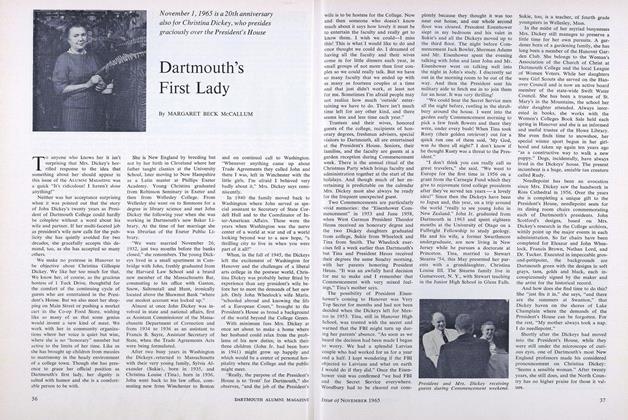

FeatureDartmouth's First Lady

November 1965 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

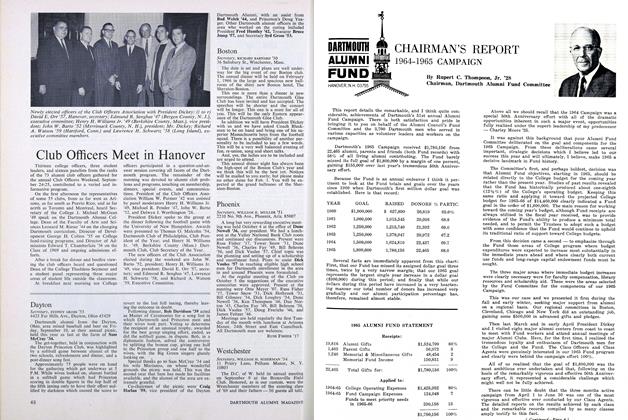

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

November 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28 -

Feature

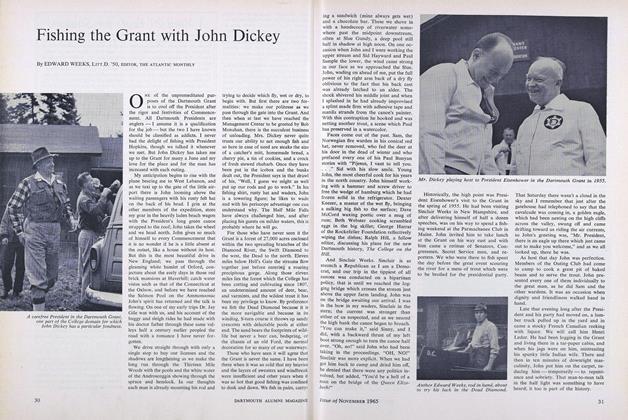

FeatureFishing the Grant with John Dickey

November 1965 By EDWARD WEEKS, LITT.D. '50,

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

December 1917 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorFRENCH LEADERS PAY HOMAGE TO THEIR AMERICAN FRIEND

JUNE 1932 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the Editor"Your're Better Because of the Bayonet"

August 1943 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

July 1949 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

MAY 1969 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorThe Greening of the Arctic

APRIL 1996